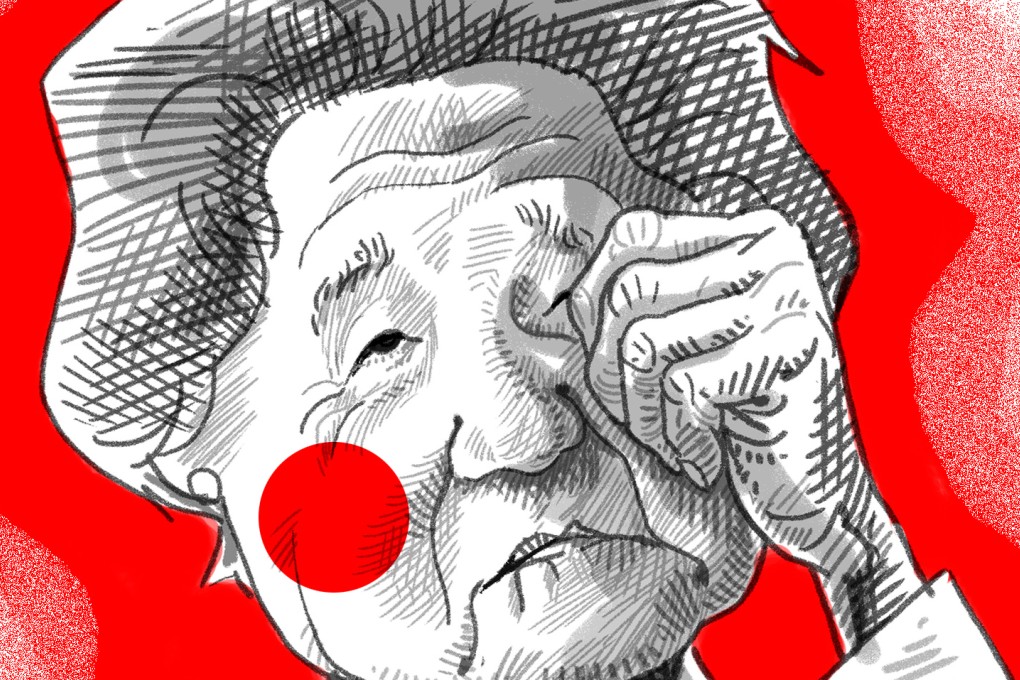

Japan’s latest apology to ‘comfort women’ just empty words without a full admission of responsibility

David Tolbert says Tokyo’s ‘remorse’ over the involvement of its military authorities in forcing Korean women into sexual slavery falls far short of what is needed

READ MORE: ‘Comfort women’ deal – compensation and apology from Shinzo Abe as rivals South Korea and Japan reach landmark deal on wartime sex slaves

The Japanese apology, which some have seen as part of a geopolitical deal struck between Japan and South Korea, has led to protests among the 46 surviving South Korean victims as well as victims in other countries occupied by Japan during the war. After working for 15 years on reparations for victims in over 50 countries, the International Centre for Transitional Justice found that many victims feel an apology unaccompanied by other forms of reparation does not constitute justice, even as material reparations, such as compensation, without a meaningful acknowledgement of responsibility also fall short.

Various expressions of regret and statements acknowledging the role of the Japanese military in operating the “comfort women” system have been made by government officials, but none, including the latest, has expressed an unconditional acknowledgment that Japan as a state was responsible.

As part of the latest “apology”, Japan pledged 1 billion yen (HK$65.2 million) for the creation of a South Korean foundation to support the surviving South Korean victims with medical, nursing and other support services. South Korea, in turn, pledged to “irreversibly” drop its demand for reparation, end all criticism of Japan on the issue and remove a memorial constructed by Korean “comfort women” survivors in 2011 in front of Japan’s embassy in Seoul.

Apologies for massive and systematic war crimes should come as a result of consultations with survivors and victims’ families

Our recent report, “More Than Words: Apologies as a Form of Reparation”, explains that the most meaningful public apologies clearly acknowledge responsibility for the violations and recognise the continuing pain of survivors and victims’ families. As it points out, apologies for massive and systematic war crimes and human rights violations should come as a result of consultations with survivors and victims’ families about the form, content and timing.