How the questioning mind of a scientist can help Hong Kong students discover the truth about beliefs such as feng shui

Paul Stapleton says in prizing evidentiary proof, science provides a tool with which to examine society’s superstitions, and must be widely taught

The feng shui master makes suggestions about improving the ‘flow of energy’ that will bring improved fortune. But this ‘energy’ has more to do with imagination than science

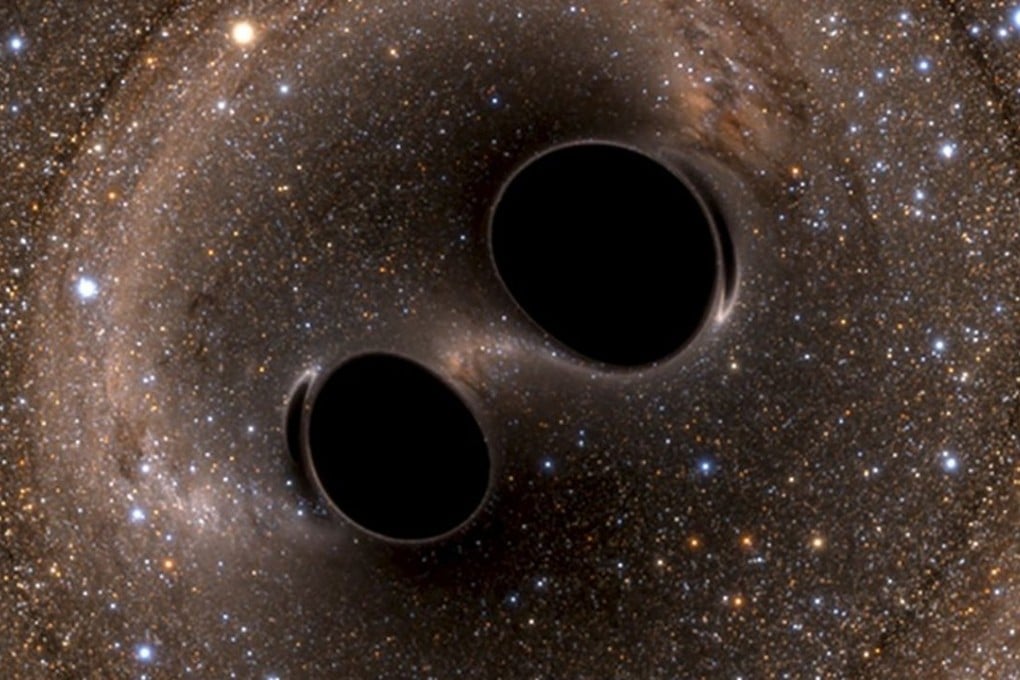

While the average person hearing the news may have some interest, the banal reality is that they would be hard pressed to understand even the most basic preliminaries of gravitational waves. But there is little wrong with that. Living in a three-dimensional world, where time appears to travel at a constant speed, it is difficult to conceptualise a space-time continuum where motion and time are not independent.

While the spotlight is on this remarkable discovery, it underscores how far we need to go in educating our youth, not just about the importance of science, but in instilling thinking that fully understands the importance of evidentiary proof – and thus a mindset that questions the many elements that stand in opposition to scientific understanding.

I speak of the myriad traditional beliefs and superstitions passed down from an era before science that remain in modern societies.

READ MORE: More Chinese parents turning to feng shui masters to name their children

Superstitions are certainly not confined to Chinese culture. Close to half of the US population are creationists.

READ MORE: Superstition flourishes as Chinese officials look to soothsayers amid uncertain times

So what educational lesson can we learn? It doesn’t mean astrophysics and quantum mechanics should be brought into the school curriculum. Rather, classes need to go beyond the mechanics of science to explaining the philosophy behind it. Meta discussions about the importance of evidentiary proof and how science uses a work-in-progress method to bring us closer to the truth need to be part of the curriculum. Thus, schools need to teach not only the “how” of science, but also the “why”, which will give students the intellectual tools to question various superstitious beliefs in society.

Such change in the curriculum could only happen in baby steps, as another type of gravity remains strong in Hong Kong schools: about half are now affiliated with religious organisations.