Awkward contortions as China moves to shore up its position on South China Sea

Zuraidah Ibrahim says last week’s statement from Beijing and three Asean members on resolving territorial claims in the region will have done little to mollify other parties

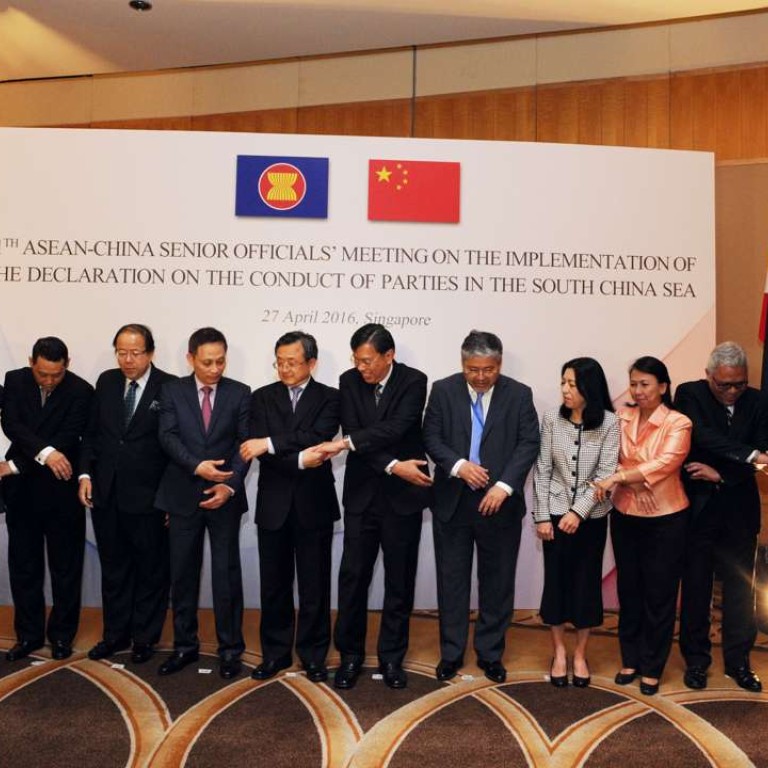

The traditional photo-op at Asean meetings is a time for smiles and the odd giggle. Leaders cross arms and link hands to form a chain of unity, which can cause amusingly awkward contortions when one has to tilt one’s body to grasp the hand of another of very different height.

China risks damaging international reputation if it rejects tribunal ruling on South China Sea disputes, US warns

It was reminiscent of the 2012 summit, which – for the first time since Asean’s founding in 1967 – ended without a joint communiqué. Host nation Cambodia had blocked any statement on the dispute, kowtowing unabashedly to the wishes of Beijing.

Last week’s development was not as startling, but it compounded Asean members’ concerns about China’s intentions and methods. The four-point consensus was a pre-emptive strike foreclosing the possibility of a show of Asean solidarity towards China’s actions in Southeast Asian waters.

After the consensus was issued, it did not take long for players to express unease, as they described China’s move as an effort to drive a wedge between Asean members. Singapore diplomat Ong Keng Yong harked back to better days: in 2002, China forged a pact with Asean on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, an initiative Wang had a hand in. “At that time, whatever Asean wants, we’d probably get it because we were the beautiful young lady that the man [China] wants,” Ong said caustically.

The diplomatic overtures come against the backdrop of heightened activity in the disputed waters over the past year. China has continued building facilities on several islets. This paper reported it will start reclamation on Scarborough Shoal this year and may add an airstrip to extend its air force’s reach over the contested waters. Chinese coastguard vessels took control of the area after a tense stand-off with Philippine vessels in 2012. In turn, the US has resumed its freedom of navigation patrols, conducting two such missions in the past six months and sending air patrols.

Speculation is widespread that China will not get a favourable ruling from The Hague tribunal, a process it has spurned from the outset even though it is a signatory to the United Nations Law of the Sea convention under which the Philippines lodged the case.

Yet, any expectation that the court’s findings will have a major impact is misplaced. International legal battles are costly, but political battles with a powerful neighbour would be costlier still.

Parties in the territorial dispute are keen to contain it, as all sides have a lot to lose if it undermines broader relations that span the gamut from economic to military cooperation. Thus, China also announced last week it will proceed with military exercises with regional countries, including the Philippines.

At some point, though, Beijing needs to tote up the price of its ostensible successes in the South China Sea. There is a reputational cost when it refuses to subject itself to international rules that it has agreed to and expects other countries to play by.

Can China exercise restraint? Will it show wisdom in its dealings with smaller neighbours? Or will it let nationalistic domestic considerations override the interests of international stability?

With satellite images tracking the surreal efflorescence of Chinese-controlled islands in disputed waters, Beijing’s ability to back its territorial claims with metaphorical and literal grit is not in doubt. Whether it can claim not just fear but also respect along the way is another matter altogether, and how it deals diplomatically with its Southeast Asian neighbours is an important test case.

Zuraidah Ibrahim is chief news editor. Twitter: @zuibrahim