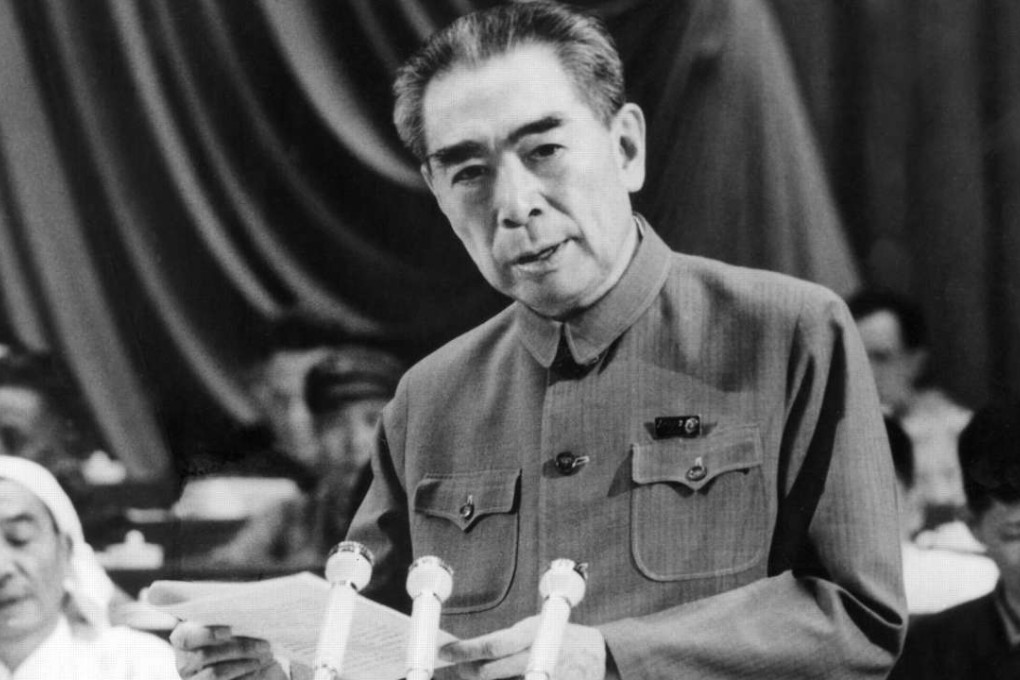

Opinion | What Beijing’s ideologues can learn from Zhou Enlai’s restraint when dealing with rebellious youth

Gary Cheung says the late premier’s pragmatism contrasts with the hardline approach taken by some central government officials towards Hong Kong’s independence advocates

Forty-five years ago last month, the American table tennis team arrived in China for a historic visit which kicked off the “ping-pong diplomacy” between Washington and Beijing. On April 14, 1971, the conversation between US player Glenn Cowan and then Chinese premier Zhou Enlai (周恩來) at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing marked the most intriguing moment of the team’s 10-day visit. The table tennis player from California had caused a media sensation by wearing a T-shirt with a peace sign on it in China.

Zhou, who was known for his charisma, said: “It appears you are also a hippie.”

If Zhou could show empathy for a young hippie, why can’t central government officials today show more understanding of Hong Kong’s rebellious youth?

Then, instead of lecturing the 19-year-old American about the ills of decadence, Zhou simply noted: “Young people around the world are discontented with the status quo and are seeking truth. Out of this search, various forms of change in thinking are bound to come forth. This is a kind of transitional period and these should be allowed.”

He went on to say: “Young people should change their course if they realise what they had done is incorrect. I wish you progress.” Cowan was impressed, and his mother sent the Chinese leader a bouquet of roses, with a message thanking him for the “wonderful hospitality shown my son”.

Zhou, who served as premier until his death in 1976, advocated a pragmatic policy towards Hong Kong. He criticised ultra-leftists in Beijing and officials from the Hong Kong branch of Xinhua News Agency, China’s de facto embassy in Hong Kong at the time, for having “mistakenly instigated” the 1967 riots in the then British colony.

If Zhou could show empathy for a young hippie who indulged in “corrupt bourgeois ways of life”, why can’t central government officials today show more understanding of the rebellious youth in Hong Kong?