Let’s hope Hong Kong bookseller saga does not mean the end of ‘one country, two systems’

Tom Plate says one must believe that the treatment of the Causeway Bay booksellers is an idiotic misstep on Beijing’s part, rather than a change of heart on a cherished principle

Deng’s recasting of China’s economy to unleash the entrepreneurial work ethic of countless Chinese meant curbing his government’s grinding enthusiasm for intervention in the economy. That one big forward burst of self-recognition and policy flexibility (too bad India’s Nehru never developed such vision) helped tee up a second Deng brilliancy: setting down as policy upon the future acquisition of Hong Kong a sensible formula to protect and enhance its success.

With ‘one country, two systems’ formula in place, Hong Kong need not fear criticism from overseas

And this meant curbing the enthusiasm of know-it-all comrades in Beijing inclined to intervene like mad in the affairs of the former British colony. Bluntly put, Deng was smart enough to know that his comrades, however otherwise capable, could not possibly be smart enough to micromanage from up north, and certainly not without greatly unnerving capable Hongkongers: and so came “one country, two systems”, the label for maximising autonomy.

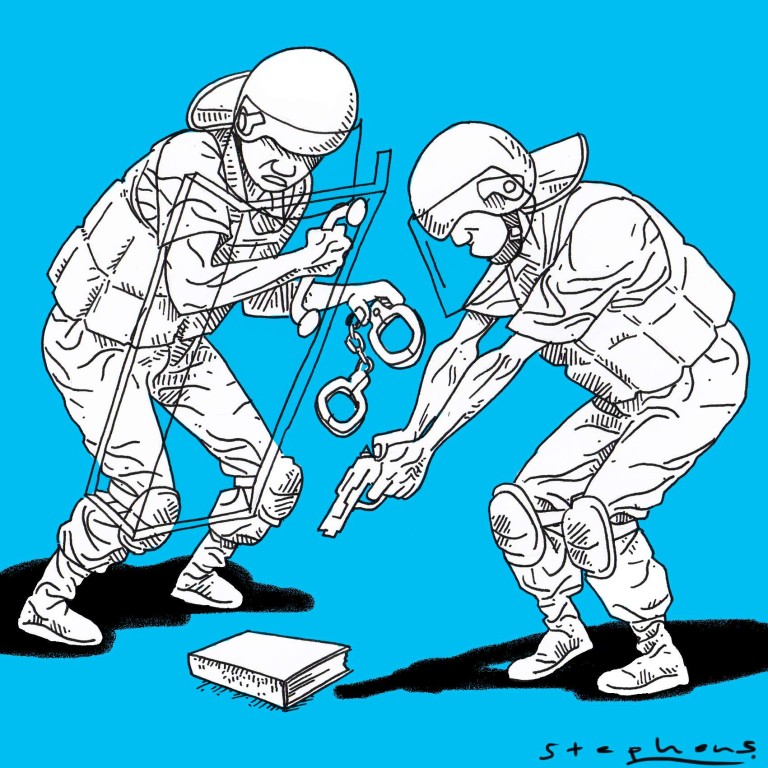

Booksellers: claims vs counter-claims

Allow me a personal note first, OK?

China’s top leaders are not smart enough to micromanage Hong Kong

My optimism came from the people I talked to and the best thinking of the time. The underrated Tung Chee-hwa, the first Hong Kong leader appointed by Beijing, seemed so sincere in his patriotism for Mother China that it had to seal Beijing’s trust (which was the only way “one country, two systems” could ever possibly work). The outgoing, ultra-articulate governor Chris Patten was so slick in his manoeuvres that I had to distrust the British pitch. And the near-pathological negativism of the Western news media, exemplified by the funereal Fortune Magazine cover, made me sad and angry – and eager to uncover a less fatalistic narrative.

Hong Kong must find the courage to restart electoral reform dialogue

Sure enough, post handover, Hong Kong flourished economically, and while the boys in Beijing had talented officials detailed to the Hong Kong remit, they otherwise sought to maintain a proper Dengian distance. Though Deng died just months before the handover in July 1997, the wise and restrained premier Zhu Rongji (朱鎔基) hovered uncle-like over Hong Kong until retirement in 2003; and the presidency of the quiet but very solid Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) that ran until 2012 must be credited for its policy of laudable minimalism. But, now, things are starting to make a pivot for the worse.

For Beijing, the management of Hong Kong was not a matter of conscience but of sovereignty – of power, not principle

But utopia always plays the waiting game, and by its infinite inaccessibility will outwait us all. For Beijing, the ultimate issue of the management of Hong Kong was not a matter of conscience but of sovereignty – of power, not principle. Who is the boss – us, not them! To reinforce this point, I revert to the timeless insight of Albert Camus. “By definition,” concluded the French literary giant and journalist, “a government has no conscience. Sometimes it has a policy, but nothing more.” It is always foolish to believe otherwise, whether the government is communist, capitalist, religious – or allegedly utopian.

So, logically, if Beijing (and not some band of one-off, overreaching idiot security people in the south) is in fact responsible for the abduction of the irreverent, but ultimately pathetic booksellers, hoping to harvest mainland renminbi by peddling dumb, gossipy books about President Xi Jinping (習近平 ), then we know that such action must reflect new policy. This means Hongkongers may have to learn to live with the current sovereign government that is their present lot – and that is not as wise as ones of recent past.

China’s top leaders simply must be too smart for such nonsense

But because of my optimism about Hong Kong – and about the enduring power of Deng’s insight – I cannot believe this to be so. I prefer the hypothesis that what happened was not policy but idiocy. China’s top leaders simply must be too smart for such nonsense, though they are not, as surely Deng would have told them, smart enough to micromanage Hong Kong.

The best move for Beijing’s leaders is to conclude, at least among themselves, that the handling of the case of the Causeway Bay booksellers is not one of the high points of their reign to date, and that when in doubt, it is always best to revert to “one country, two systems” as if it were chiselled in stone. It is, after all, one of the wiser legacies of modern China’s smartest maximum leader.

Columnist Tom Plate is the author of “In the Middle of China’s Future” and Loyola Marymount University’s Distinguished Scholar of Asian and Pacific Studies in Los Angeles