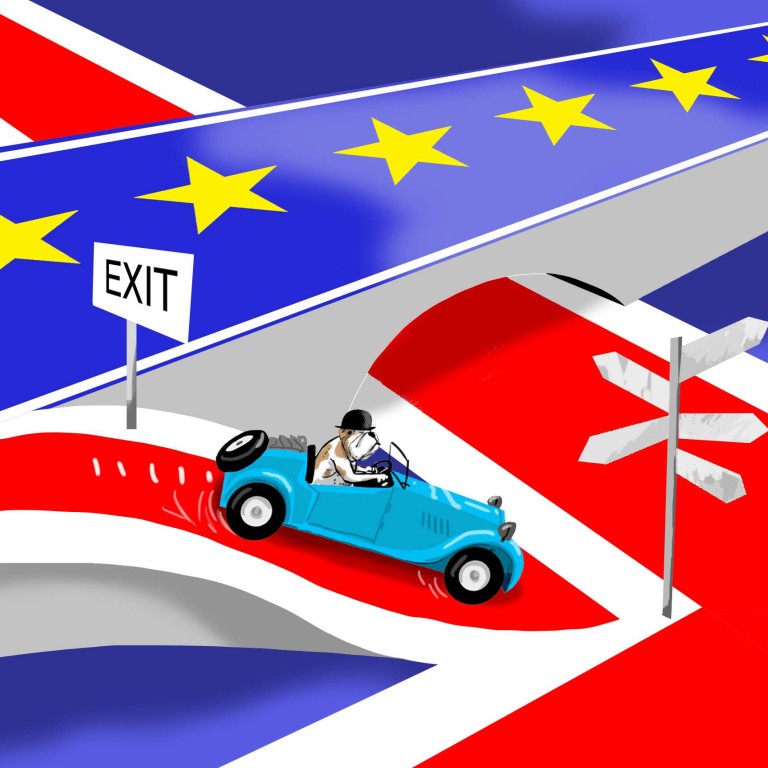

Historic Brexit vote will test the strength of the union in Europe – and within the United Kingdom

Andrew Hammond says decisions taken in the coming weeks after the British people’s landmark vote to leave the EU will be critical, while both British and EU leaders try to contain the political and financial fallout

It’s Brexit: Hang Seng Index plummets as Britain votes to leave EU in stunning referendum result

The decision has rattled financial markets and the UK political establishment, and it put immediate pressure on Prime Minister David Cameron to resign, which he has now announced he will do, only a year after his landmark general election success in winning the first majority Conservative government for over two decades. A major reassurance effort is now under way to respond to the political trauma and financial uncertainty with the European Central Bank, Bank of England and other central banks preparing to make potentially further significant interventions to respond to market volatility.

While the immediate political action remains in the UK, with the spotlight on Cameron, Brussels will be centre stage next Tuesday and Wednesday with a previously planned EU summit of national leaders. The EU elite will be shell-shocked by the result, not least given fears about political contagion to other countries potentially looking to leave the union in future years, and European political leaders will now seek a coordinated front to emphasise the continuing resilience of the EU project.

If Britain does leave the EU, it will be a mess of David Cameron’s own making

In this turbulent context, Cameron had to decide whether or not to resign immediately, with his position destabilised. There were significant shows of support for him from within the Conservative Party, with around two-thirds of exit-backing Conservative MPs, including former London mayor Boris Johnson and Justice Secretary Michael Gove, having signed a letter saying he should stay in office.

Despite this, the prime minister was aware that the Conservative backbenches may have become significantly more ungovernable under his premiership. And, an internal leadership challenge against him, which requires 50 Conservative MPs to trigger, could not be ruled out.

One further option which cannot be completely ruled out is a second EU referendum if better terms can be secured from Brussels

The government’s small parliamentary majority could mean a more embattled administration as intra-Conservative tensions fester. That also happened in the 1990s, under the government of John Major after Britain was ejected from the then European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992. And such political troubles will undermine key elements of domestic policy, including the government’s plans to try to secure some £30 billion (HK$345 billion) of spending cuts.

Cameron said he thinks a new prime minister should decide when to trigger Article 50 of the EU treaty, the formal mechanism for bringing about the UK’s withdrawal process. One other possibility, suggested by some Leave campaigners, would be for Britain to leave the EU by deploying alternative legal/legislative procedures, including by repealing the 1972 EU Communities Act. However, some lawyers and constitutional scholars have dismissed the feasibility of this, and indicated that Article 50 is the most viable route.

One further option in the coming months, which cannot be completely ruled out under a new prime minister is a second EU referendum if better terms can be secured from Brussels. Even some exit campaigners such as Johnson have advocated this in the past, despite the fact that it would infuriate many of those who voted Leave on Thursday.

After the Brexit vote, just who will clean up the mess?

Favourites to replace Cameron would be Johnson and other key exit supporters, including Gove, although the prospects of some who favoured Remain, including Home Secretary Theresa May and possibly Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson, could not be dismissed. However, the leadership ambitions of Chancellor George Osborne, a close ally of Cameron, now appear sunk.

In this context, Cameron’s successor as prime minister may well seek to engineer a general election if it is believed the outcome will be favourable to the Conservatives to try to secure a strong electoral mandate. While the current Parliament theoretically runs to 2020, the new Conservative leader would be in a good position to challenge opposition parties to support him in calling an early ballot, given the change of prime minister, and the potential gravity of the situation facing the country.

As Brexit verdict deals devastating blow, is this the death of the European Union?

The vote will have potentially massive implications for the longer-term future of the EU and Britain. On the latter front, for instance, Brexit will increase the likelihood of a second Scottish independence referendum vote. Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish National Party leader, has previously argued that the UK should only exit the EU if all four constituency countries (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) individually voted to leave, an exceptionally unlikely scenario.

Turning to the EU at large, the Brussels-based club now faces the biggest potential reversal in its history of more than half a century. As one of the more influential European states, a UK exit will disrupt the balance of power, inner workings and policy orientations of the EU in a way that could ultimately consolidate the influence of other large states, especially Germany.

Taken overall, the historic decision will set the political weather in both Britain and Brussels for months to come as political leaders scramble to come to terms with it. Decisions taken in the coming weeks will define the longer-term political and economic character of the EU and United Kingdom, with both unions now facing major stress as the implications of the referendum sink in.

Andrew Hammond is an associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics