Opinion | Bookseller saga is an affront to Hong Kong people’s sense of freedom and autonomy

Gary Cheung says Hongkongers are usually pragmatic people but the treatment of Lam Wing-Kee and the other booksellers should alarm them – and requires a full explanation from Beijing

Most Hong Kong people are pragmatic and seldom champion high-sounding ideals. They may be uncomfortable with the white paper issued by the State Council in 2014, which stressed the central government’s “comprehensive jurisdiction” over Hong Kong. They were frustrated with Beijing’s stringent framework for electing the chief executive, which gave no chance for pan-democrats to back the Hong Kong government’s package for choosing the city’s leader by “one man, one vote” in 2017.

Yet most Hongkongers have yet to reach boiling point as they come to terms with the reality of failing to attain full democracy in the near future (or even in their lifetime) and Beijing’s growing assertiveness.

However, the bookseller storm has touched a nerve with a substantial proportion of Hong Kong people.

Hong Kong lawmakers call for review of scope of notification system in wake of bookseller detention cases

Causeway Bay Books co-founder Lam Wing-kee caused a sensation by revealing two weeks ago his eight-month detention ordeal on the mainland. He claimed he was abducted by agents from a central special investigation unit after crossing the border into Shenzhen last October. He said he was first taken, blindfolded and handcuffed, from Shenzhen to Ningbo (寧波) by train. In Ningbo, he was detained in a facility where he was watched round the clock and faced repeated interrogation.

Lam said the people who detained him had forced him to sign a form in which he agreed not to inform his family of his situation, and that he would not hire a lawyer. The move obviously contravenes the Criminal Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China, which states that “where residential surveillance is in a designated location, the person’s family shall be notified within 24 hours”. The law also says that, from the day the suspect is first interrogated, he has the right to hire a lawyer.

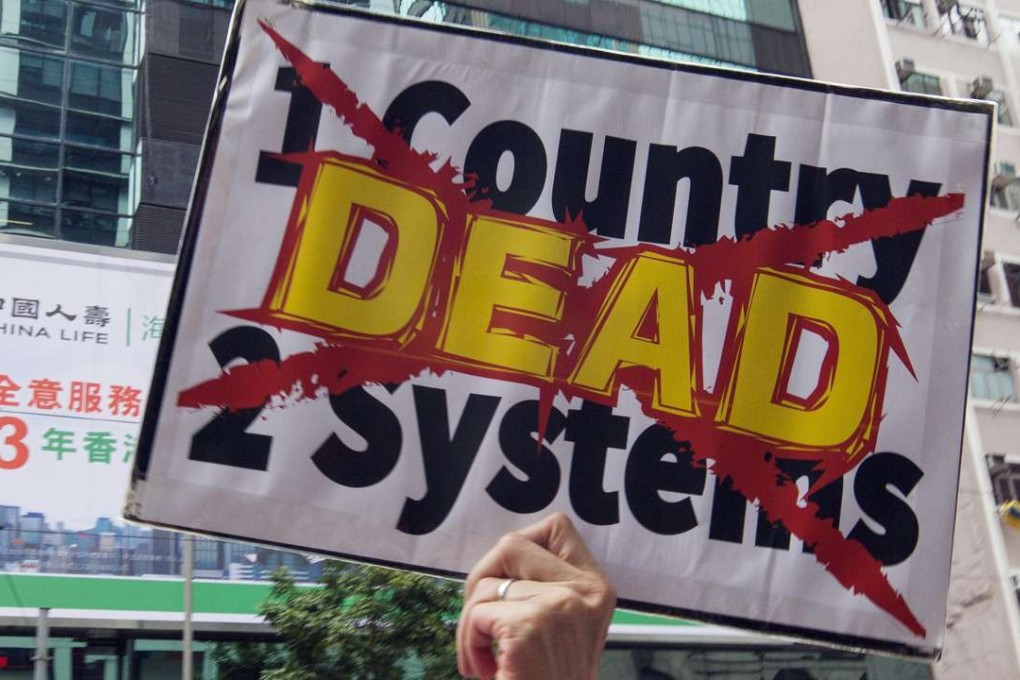

According to Lam, two mainlanders who escorted him back to Hong Kong on June 14 were officers from the special investigation unit. They gave him a smartphone and demanded that he report his whereabouts via text messages. If his account is accurate, the acts of the two mainlanders amount to enforcing laws in Hong Kong and call “one country, two systems” into question.

Days after Lam revealed the harrowing details of his detention, a woman claiming to be his girlfriend unleashed a scathing attack on him, calling him a “liar” and “not like a man”. The woman accused him of having “completely ruined the image of Hong Kong’s men” and having lied to her about the legality of banned books when persuading her to help distribute them.