On South China Sea disputes, politicians should step up where legal scholars have failed

Daniel Fung says maritime territorial disputes that are full of historical baggage cry out for a diplomatic solution, as any attempt at a resolution through arbitration – as The Hague tribunal tried – will necessarily fall short

Attempts to establish an international legal regime to govern the seas and oceans reached an apogee with the advent of the Law of the Sea treaty in 1982, to which China acceded in 1996 but which the US singularly refused to ratify. Not that such minor detail in any way inhibits American criticism of China’s stance while simultaneously ignoring the inconvenient truth of the US’ own failed challenge in 1986 to the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice to determine the legality of American military support for the Contras to topple the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua. America would neither participate in the litigation initiated by Nicaragua, nor abide by the court’s ultimate decision in favour of that nation.

China against the world: A tale of pride and prejudice

No doubt China bears some responsibility for the one-sided nature of the Western narrative since it chose ill-advisedly to cede public forensic space to those of an opposing point of view, and is therefore the author of its own misfortune.

This default outcome does not, however, absolve the global community from addressing the real question – is Western punditry correct? Is China at the end of an agonising two centuries of partially failed modernisation, condemned to be a rising power chafing under constraints imposed by a pre-existing order and failing to rise to the challenge? Is China fated to be a rogue state just like Wilhelmine Germany? Or might such a sense of Hegelian determinism be premature?

History casts doubt on the validity of the Western narrative and suggests that the issues raised by the Philippines are so freighted with historical baggage as to render them non-justiciable. In other words, such issues are unsuitable for determination by arbitration, much as in a comparable domestic context, the judiciary declines to adjudicate on matters touching on defence and national security, deferring to the nuanced political judgment of the executive branch of government.

Justice not served by tribunal’s ruling on South China Sea

Against this backdrop, the question arises whether international law is sufficiently developed as a system to resolve fundamental disagreements over complex questions of contested sovereignty. This issue is inseparable from ones concerning the subtlety, depth and competence of arbitrators to adjudicate on historically complex and politically sensitive questions.

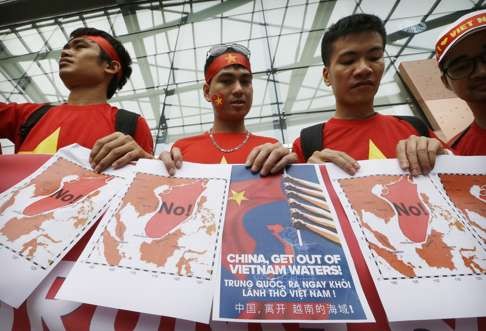

The first question is whether the tribunal was supplied with sufficient historical material to form a comprehensive judgment. Related to this is the fact that other countries having claims or being in de facto occupation of part of the Spratlys – such as Vietnam and Indonesia – are not joined as parties to the arbitration. This constitutes a bar to the justiciability of such issues.

A further weakness of the tribunal’s ruling is its presentation in a vacuum, absent historical context and relevant fact. The South China Sea was profoundly disturbed by colonial and imperial encounters

In a striking failure to address the issue of justiciability, the tribunal ruled that upon accession to the Law of the Sea treaty in 1996, China relinquished all historic claims encapsulated within the “nine-dash line”. This ruling ignores the inconvenient truth that, upon accession, China specifically excluded from the treaty’s purview questions of territorial sovereignty and delimitation of maritime boundaries, a reservation allowed under Article 298. In registering such an exclusion, was China a rogue state? Not only is the answer no, but all permanent members of the UN Security Council registered a similar exclusion – except the US. Twelve members of the G20 did the same.

A further weakness of the tribunal’s ruling is its presentation in a vacuum, absent historical context and relevant fact. The South China Sea was profoundly disturbed by colonial and imperial encounters. For more than a century from the First Opium War in 1839 till way past the Sino-Soviet conflict in 1968, China was in constant crisis, subject to periodic invasion, stricken by civil wars and, until the 1990s, unable to act effectively on the international stage. Vietnam was locked in a destructive conflict with two Western powers, France and the United States, for a century from the 1870s to 1975. For much of this period, the Philippines and Malaysia did not exist as sovereign states.

Over the same period, three imperial powers, France, Britain and Japan, exercised immense impact on the region. Two of these have vanished from the scene and have yet to account for their former presence.

As the research of Professor Tony Carty demonstrates, the UK Foreign Office legal advisers concluded in 1974, following years of painstaking examination, that China had the strongest legal claim to sovereignty over the Spratlys, superior to those of, respectively, France, Vietnam and the Philippines. Following the French retreat from Indochina after the defeat at Dien Bien Phu, France effectively abandoned all claims to the Spratlys. The weakness of the Vietnamese claim is underscored by the fact that the French claim was made on behalf of France rather than French Indochina.

The weakness of the Philippine claim is underscored by a US State Department statement made in response to a French foreign ministry inquiry in the 1930s that the jurisdiction of the Philippines ends at the water’s edge in its main archipelago and does not extend into the South China Sea, let alone the Spratlys. The Philippines had further arguedthat, after Japan’s defeat in 1945, the islands became terra nullius and could be made the subject of occupation, which the Philippines attempted, like Japan did before. This argument presupposes that Japan had acquired the title, which extinguished the earlier Chinese title, an argument rejected by the UK Foreign Office.

Despite this unhappy South China Sea ruling, Beijing must not turn its back on international law

Further, it ignores four key facts:

First, centuries of seasonal occupation by Chinese fishermen. According to US sources, China’s claims date back to the 15th century, not merely through maps but because the islands have been visited annually since time immemorial by Chinese fishermen collecting sea cucumber and turtle.

Second, the Allies’ position made in the Cairo Declaration in 1943 that all Japanese-occupied Chinese territory be returned to China upon the defeat of Japan.

Third, nationalist China’s recovery of the Spratlys in 1946, in particular Itu Aba, then renamed Taiping Island.

Fourth, consistent US State Department conduct through till at least 1960 in seeking permission from nationalist China for US warships to visit the Spratlys, including the submission of names of senior visiting personnel. Little surprise, then, the UK Foreign Office’s conclusion on the issue of sovereignty over the Spratlys that “China is left cantering past the winning post”.

The makings of a South China Sea agreement between Beijing and Manila

The above illustrates a basic truism of international relations, namely, that sovereignty issues freighted with historical baggage and political sensitivity cannot be properly resolved by arbitrators, no matter how experienced or expert, but must be addressed by diplomatic settlement – this time by tying up all the loose ends left unresolved at the San Francisco peace conference, where in 1951 Japan relinquished all claims to the South China Sea including the Paracels and the Spratlys, but left unnamed the country to which such islands reverted. The existence of such loose ends is unsurprising since, with the inception of the cold war and the Korean war, the People’s Republic of China was pointedly not invited to San Francisco. In other words, the present conundrum cries out for a resolution – with the obvious and essential participation of China.

Rather than be confronted by a rising China labouring under the neuralgia of victimhood and condemned to a replay of the Wilhelmine tragedy, the family of nations, more particularly the US and China, should rise above the fray to resolve the issues of the Western Pacific, specifically those of the South and the East China seas, by comprehensive settlement, thereby converting crisis into historic opportunity.

Daniel R. Fung is president of the International Law Association, Hong Kong Chapter, and founding president of the Asia-Pacific Institute of International Law