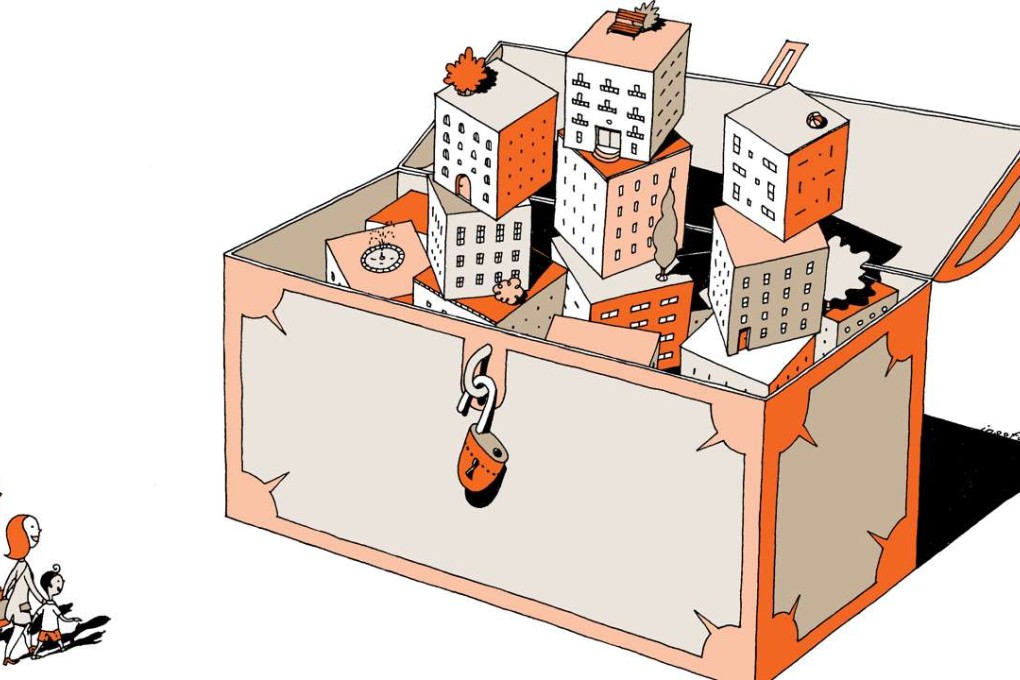

Hong Kong needs property developers that put social mission ahead of profit

Yanto Chandra says the government must work with all stakeholders to start giant social enterprises that will carry out on a massive scale successful projects such as Sham Tseng Light Housing

It’s the year 2025. Thirty per cent of Hong Kong’s population lives in affordable housing. But who are the property developers? They are social enterprises who work transparently: they openly share their costs (e.g., land acquisition, materials, and labour) and add 2-3 per cent as profit margin. They are not profit-hungry. These social enterprises embrace the “asset and profit lock” principle, so that one day if they are dissolved, all assets and profit must be reinvested for the community, not pocketed by the founder(s).

These social enterprises are gigantic organisations, with large capital drawn from investment by impact investors, big companies’ corporate social responsibility contributions, and donations by large foundations. Their lands are donated by (or sourced at low price from) the Hong Kong government. They attract thousands of volunteers each year and social enterprise contractors who help construct and manage the housing projects.

Hong Kong government teams up with social enterprise to provide cheap housing for as many as 90 families

The old and young in Hong Kong no longer need to labour for 30 years to buy a tiny flat because these affordable homes cost only a third of those offered by private housing estates. The social enterprises grow further by going public (selling their shares to impact investors) and reduce social inequality in Hong Kong – their models replicated all around the world.

We have had enough of cage housing, sub-divided flats and the long queues for public housing

Rewind to 2016. The urban housing crisis has been a headache for chief executives and housing ministers in the SAR government for years. We have had enough of cage housing, sub-divided flats and the long queues for public housing. It is time for Hong Kong to think and do something beyond the conventional public housing model and work collaboratively with all stakeholders – the government, businesses, non-governmental organisations, impact investors, philanthropists, and the social enterprise sector – to start gigantic property development social enterprises.

New venture, Light Be, helps needy find a room of their own - for cheap

How affordable is the rent? It is calculated based on the tenants’ income, and ranges from HK$3,000 to HK$5,000; offering higher quality and eventually more cost-effective housing than sub-divided flats. Light Be sends social workers to help the families and even tutors to help with the children’s education. They empower the families by providing job opportunities and training. In a few years, the families can be financially independent.