Trump’s self-defeating vision of Fortress America must not become reality

Timothy Webster says the president-elect must understand that the US draws its hard and soft power from a deep engagement with the world. To turn its back now won’t ‘make America great again’

Blaming globalisation is palatable, linking frustration over one’s economic insecurity to foreign nebula beyond one’s control. But, like all forms of scapegoating, it offers at best an incomplete explanation. At worst, it distracts attention from efforts to address the underlying problem. It also risks alienating much of the outside world.

Anyone who has read headlines over the past year has some idea of a possible Trump foreign policy. From tariffs on Chinese exports to a reinforced border with Mexico, Trump’s pronouncements can be divided into three basic categories.

Trump appoints three hardliners to national security and attorney general positions

The basic building block is, of course, the wall: the one that Trump promised to build on America’s southern border. But other walls loom. A ban on Muslims – later modified to a pledge on “extreme vetting” – could affect over a billion people attending US universities, patronising the country’s hospitals and clinics, investing in US companies and real estate, and so on.

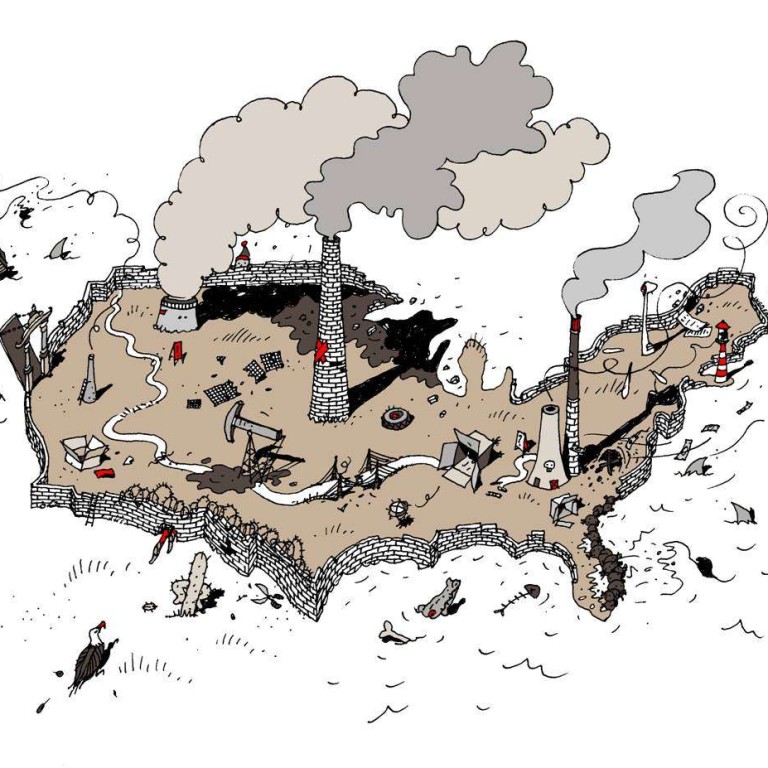

Fortress America made for a potent campaign symbol, but it would set the country back at least a century

Rescinding trade deals would, likewise, raise barriers to trade and investment that the US government, under both Republican and Democratic administrations, has actively dismantled for the past 35 years.

A second theme is the realignment of alliances and institutions. If our allies do not pay up, Trump says, the US cannot afford to provide the security blanket covering much of the world. Never mind that these alliances literally empower the US to project military power from Germany to Japan in ways that no other country in the world can. More specifically, the disintegration of Nato – an organisation that fought alongside the US in Afghanistan – would not only imperil peace and security in Western Europe, it would also subject eastern and northern Europe to further Russian encroachments.

Indeed, Trump’s closeness with the Russian government should give us pause, not because Russia is the successor state to the US’ former Soviet enemy, but because of Vladimir Putin’s interference with US democratic processes, his authoritarian stifling of domestic opposition parties, and the sabre-rattling throughout the Eurasian continent.

The onus is on Trump to make the correct pivot to Asia

Trump has also suggested weakening – if not severing outright – treaty commitments to allies such as Japan, South Korea and the Philippines. This would destabilise a region roiled by unpredictable nuclear tests on the Korean peninsula, rising maritime tensions in the South and East China seas, and growing doubts about the US ’ commitment to the region. This would weaken American resolve at the very moment that China is playing a more assertive role in the region.

The US wrote the very rules Trump seeks to undermine

A third element involves rewriting the rules of the liberal world order. Globalisation failed us, it would seem, because the rules did not serve American interests. The problem with this argument, of course, is that the US wrote the very rules Trump seeks to undermine. Many Americans fail to recognise that the US helped establish, and subsequently support, international institutions such as the UN, the World Trade Organisation, and the International Monetary Fund. American officials wrote these institutions’ charters and articles of association, drafted treaties and monitored enforcement. The US still exercises considerable influence over these institutions.

Beginning with the Marshall Plan, the US has devoted considerable energy to economic engagement with the rest of the world. America could not trade with a war-torn Europe in 1945 any more than it could with an impoverished China in 1978. Subsequent decades of engagement – through foreign aid, trade, investment and other forms – have made the world a richer place, and allowed the US to exert enormous influence around the world. If Trump turns his back on the world order that his predecessors in the White House strived so hard to create, he will forgo critically important sources of US power.

Why China’s best response to Trump is to drive consumption, boost household incomes

Under the terms of these deals, partner countries generally open their markets to American commercial interests, ensure a basic level of treatment of American companies, and abide by environmental and human rights standards. They also permit American corporations to operate in their jurisdiction, wherein these companies disseminate ideas about markets, rule of law, labour relations and technology. Of course, free trade has also led many corporations to close factories in the US, set them up abroad and export foreign manufactures back to American consumers. This has jeopardised the employment prospects for many working Americans.

But withdrawing from Nafta (or any other institution) will not bring back manufacturing jobs. Slapping tariffs on imported goods will pique trade tensions and raise the likelihood of retaliation. It will also make other countries – allies, partners and competitors alike – far less willing to cooperate with the US on the Pandora’s box of transnational threats that Trump will face upon taking office: from terrorism and pandemics to nuclear disarmament and regional stability.

The US is at its most powerful when engaging deeply with the outside world. As a businessman, Trump has benefited handsomely from globalisation. He has real estate holdings on four continents, and produces brochures for his luxury residences in English and Chinese. He deploys Honduran, Chinese and Indonesian labour to produce clothes for his Trump Collection. He should use the same acumen to increase American economic engagement with the rest of the world. Fortress America made for a potent campaign symbol, but it would set the country back at least a century in terms of economic engagement, military preparedness, soft power and other traditional strengths.

Timothy Webster is assistant professor of law and director of East Asian Legal Studies at Case Western Reserve University, US