Hong Kong lags behind in the battle against modern-day slavery

Lowell Chow says supply chains are feeding the scourge, and the law, governments and communities must all be on guard to help the 45 million victims of forced labour worldwide

As some experts point out, the issue is not child labour alone. The employers confiscate the children’s identity papers and do not pay wages until the end of the year, so as to prevent them from walking away from the job. This constitutes bonded labour, one of the many forms of forced labour.

Yet, a new benchmark by KnowTheChain found that, in the global garments industry, action to tackle the scourge is lacking.

Finance, wealth and ... slavery? Hong Kong one of Asia’s worst for forced labour

The benchmark did identify leading practices from some brands. Highest-scorer Adidas (81/100), for example, has strong processes in place to enable workers to organise and safely lodge grievances. It also takes steps to prevent exploitation during the recruitment process by favouring direct, permanent employment and establishing the requirements for recruitment agencies when they are used.

Watch: Modern day slavery and supply chains

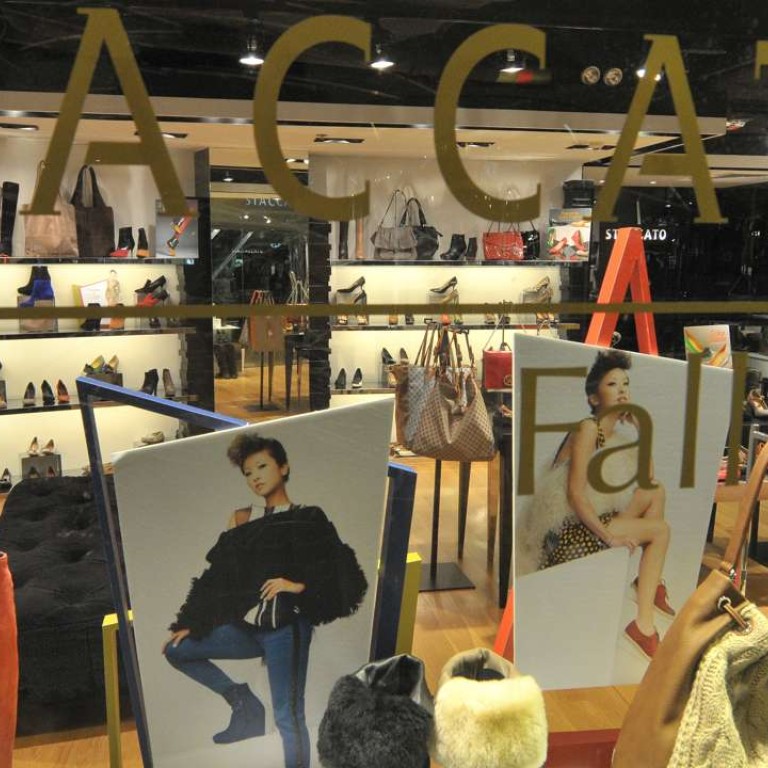

Luxury brands – including Hugo Boss, Kering (owner of the Alexander McQueen, Gucci and Stella McCartney labels), Prada and Ralph Lauren – scored much lower overall than high street retailers such as Adidas, H&M, Inditex or Primark, with none getting an above-average score.

Hong Kong’s helpers overworked, burdened with debt and suffering forced labour – new report demands new regulations and an end to the live-in rule

Another factor that should drive greater disclosure in this region is the expectation for Hong Kong-listed companies to report their approach to social, environmental and governance issues.

Watch: ‘Narcos’ actor Wagner Moura’s message on the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, December 2

Cotton and leather are both among the goods produced by forced labour in China, the world’s largest cotton producer and exporter, for example.

Moving up the chain, forced labour is also prevalent in the manufacturing stages.

It affects both internal workers and foreign migrant workers across regions in Asia, Latin America and the Middle East. Clothes that we buy in Hong Kong could come from any of these locations, bearing risks of forced labour.

The world is watching what companies are doing to end modern-day slavery: it is time for corporates headquartered in China and Hong Kong to step up their game.

Lowell Chow is Greater China senior researcher and representative at the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre