It’s now or never for a Hong Kong archives law, as British files reveal

Gary Cheung says declassified files on a 1987 Sino-British deal over direct Legco elections underline the need for louder calls to preserve the city’s public records, especially in view of the upcoming chief executive election

The secret deal was struck when a consultation on the development of a representative government was under way. The local government was criticised at the time for manipulating the views of some Beijing-friendly groups to ensure that no clear mandate for direct elections in 1988 emerged, even though many surveys showed more than 60 per cent support.

Then now: a paper trail to where?

Maintenance of public records is vital for institutional memory and a key component of good governance

I went through a number of declassified files relating to Hong Kong from 1986 to 1989 and, as a supporter of the introduction of direct elections for 1988, I was furious to learn how democratic development was delayed because of the behind-the-scenes deal.

Fresh call for archive law to halt destruction of documents

Hong Kong’s No 2 official makes ‘leadership pitch’ in Palace Museum row

The absence of an archives law leaves it up to bureaus and departments to transfer documents to the Government Records Service. In 2014, the offices of the Chief Executive, the Chief Secretary and the Financial Secretary – the nerve centre of the administration – transferred a total of 130 records to the service. That accounted for 0.2 per cent of the total records from all government departments transferred to the government archivists that year.

The absence of an archives law leaves it up to bureaus and departments to transfer documents to the Government Records Service

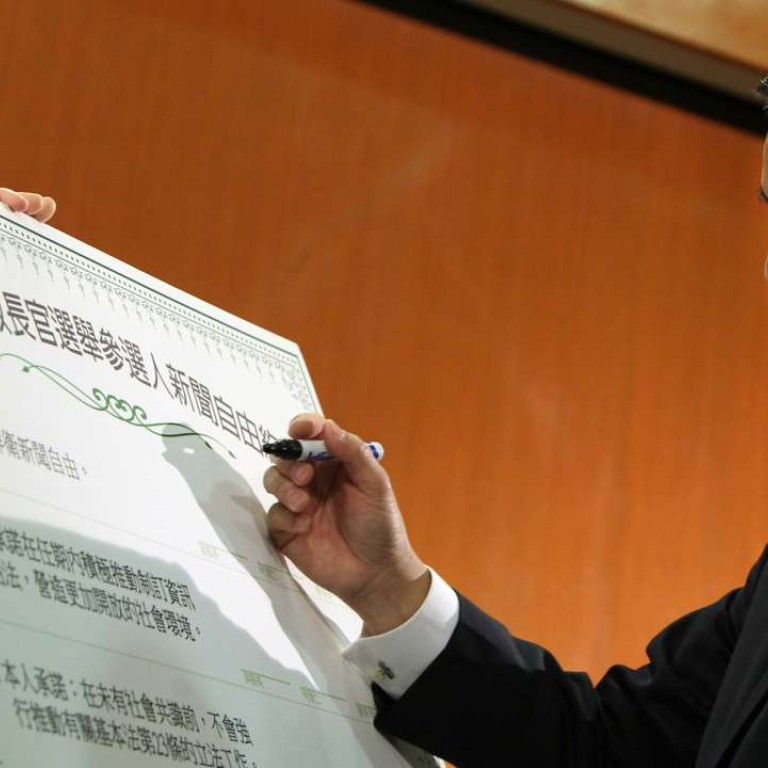

Retired judge Woo Kwok-hing, who will be contesting the chief executive election in March, has pledged his support for enacting an archives law. Another candidate, Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee, said she supported the move “in principle”.

It remains to be seen if Lam and John Tsang Chun-wah, also expected to join the race, will endorse the idea. It is time to renew the momentum for an archives law before it is too late.

Gary Cheung is the Post’s political editor