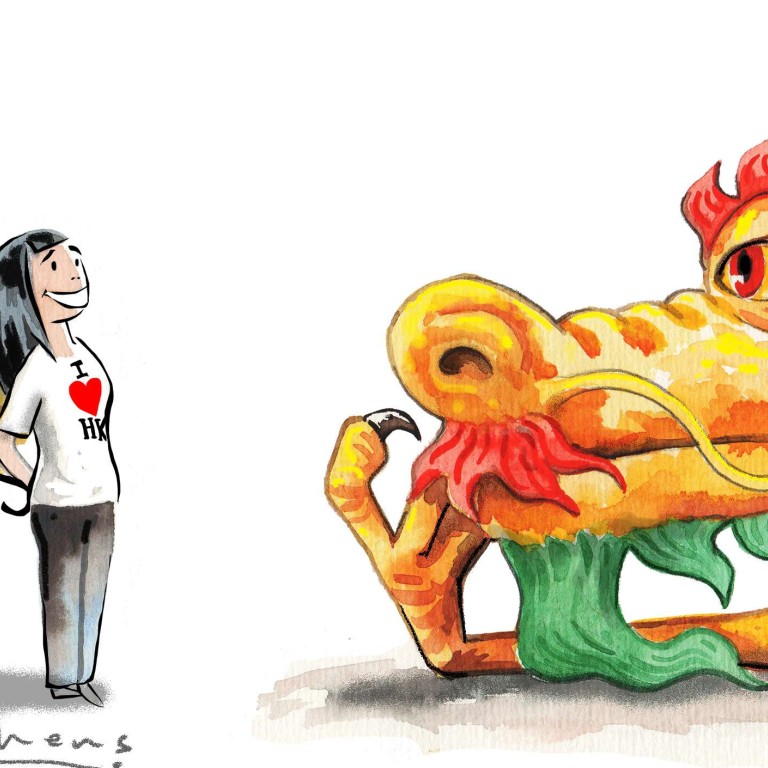

Can battered Hong Kong regain some of its dignity in the eyes of Beijing?

Michael Heng says events like the 2014 Occupy protests could have been handled much better if all those involved had adhered to the ‘one country, two systems’ principle

To the vast majority of Hongkongers, the idea of independence is simply and obviously untenable.

Watch: Hong Kong 2016 in 60 seconds

Hong Kong has long been known for its pragmatism, tolerance, culture of moderation, openness and vibrancy. So, today, it is natural to ask: what has gone wrong?

It was a year when a movement for greater democracy in September morphed into a massive street demonstration, known the world over as the “umbrella movement”.

Anyone with political common sense would know that what happens in Hong Kong will have repercussions in Taiwan.

And so it is important to recall that the Occupy movement in September 2014, came just two months ahead of local elections in Taiwan.

Given this small time gap and Hong Kong’s usual self-restraint, it is perhaps puzzling that the Occupy movement was not handled with more sensitivity, skill and wisdom. It was certainly not an event that merited descriptions of moderation, magnanimity or far-sightedness.

Hong Kong’s image of moderation and pragmatism has been dented by the sequence of events since 2014

In the absence of reliable information, I could only offer a conspiracy theory of sorts – that, perhaps, the crazy mess in Hong Kong was connected with power conflicts at the very top of the Communist Party. Perhaps those in Zhongnanhai responsible for Hong Kong wanted to embarrass President Xi Jinping ( 習近平)?

As expected, the KMT suffered a disastrous defeat, which demoralised the party and created a favourable political environment for the Democratic Progressive Party in the general election in January last year.

Taiwan election: Tsai Ing-wen is Taiwan’s first female president after landslide victory in historic poll

Taiwan now has a DPP president and vice-president, and the party enjoys a majority in the Legislative Yuan. This political configuration is not something that Beijing had hoped for, or wants to see.

Moreover, Hong Kong’s image of a city of restraint and pragmatism has been dented by the sequence of events since that fateful month in 2014. What can the city do to rebuild its image?

Luckily, there is very little support in Hong Kong for the idea of independence. Based on this, we may conclude that Premier Li’s warning was primarily intended for his audience on the mainland.

For Hongkongers, of greater relevance was his statement that Beijing is committed to the principle of “one country, two systems” and the framework would be applied without being “bent or distorted”. He told the NPC: “We will continue to implement, both to the letter and in spirit, the principle of ‘one country, two systems’, under which Hong Kong people govern Hong Kong.”

Premier Li Keqiang’s warning on Hong Kong independence highlights Beijing’s displeasure

[The ‘one country, two systems’] principle has largely enabled the continued prosperity of the city over the past 20 years

It is this principle that has largely enabled the continued prosperity of the city over the past 20 years, without undermining its pragmatism and spirit of inclusiveness.

Coming from the mouth of the second most powerful man in the political establishment in Beijing, these words essentially lay down the parameters of political life in Hong Kong. This part of his speech was addressed to the people in Hong Kong, especially to those holding the levers of power.

Michael Heng is a retired professor who had academic appointments in Australia, the Netherlands, and at six universities in Asia