Advertisement

Why Trump’s budget boost won’t actually strengthen US defences

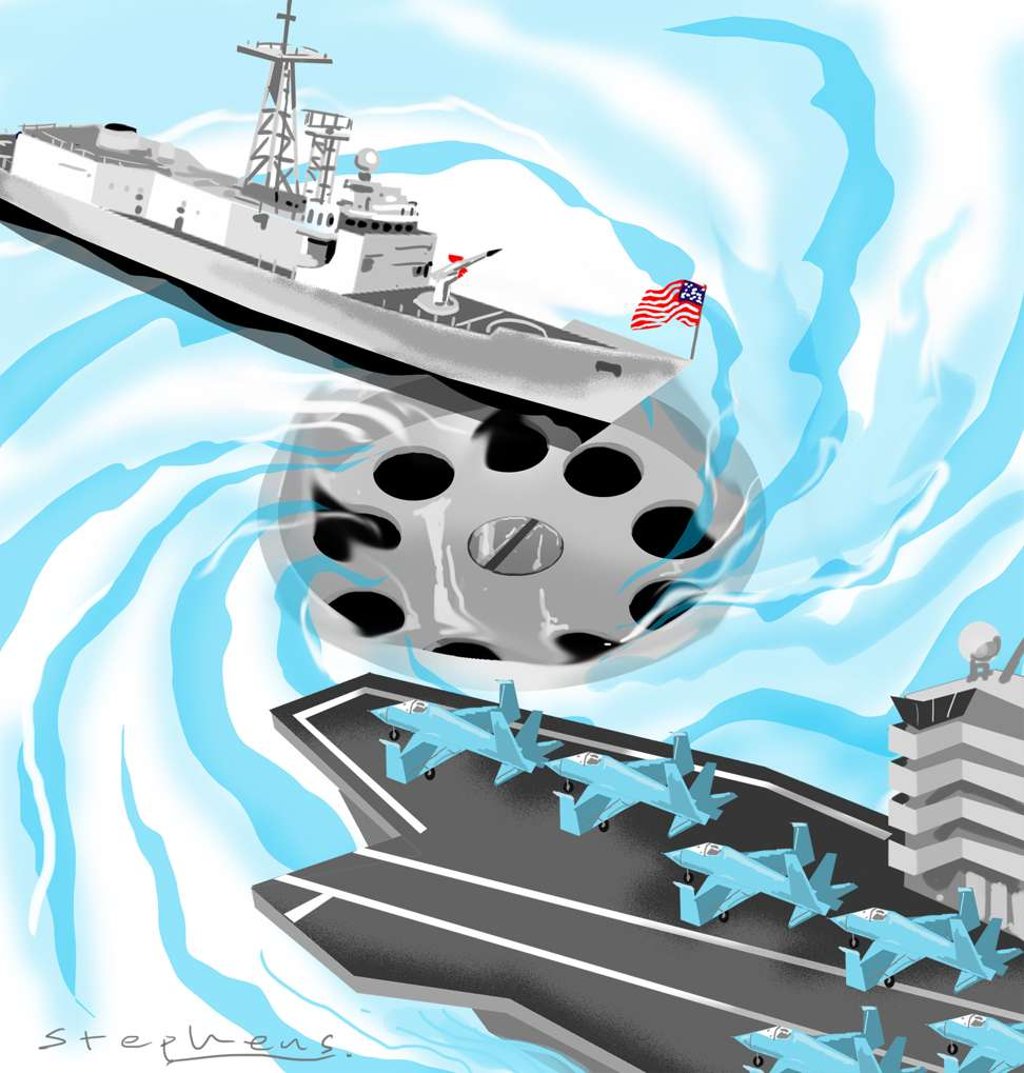

Hugh White says the US president’s proposal for a ‘historic’ raise in military spending sounds dramatic but is frankly underwhelming – both in its amount and intended use

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

But it would be a mistake to see the president’s defence budget announcement this way. There is much less to it than meets the eye, and little that offers any serious hope that America under Donald Trump will respond effectively to the strategic challenges that it has inherited from Barack Obama.

Let’s start with the numbers. As always with defence budgets, there is a much scope for confusion, but however you cut it, Trump’s boast of a historic 10 per cent rise in defence spending looks overblown. The White House itself has reportedly acknowledged that the spending proposed for the next fiscal year is only 3 per cent above this year’s projection, and inflation will eat up most of that. The amount of extra money actually flowing into building and maintaining combat capabilities is thus going to be very limited at best.

Advertisement

What difference any extra money makes to America’s ability to meet its challenges depends of course on how it is spent. So far, there are few details, but Trump’s focus is plainly on big-ticket, high-profile major equipment. His centrepiece is a plan to expand the US Navy to 350 ships, from the current 274. There are several problems with this approach.

Advertisement

For one thing, this may not address the most urgent constraints on US military power. Like many modern militaries, US forces struggle to find the funds to maintain and operate the capabilities they already have. Filling these funding gaps is often the most effective way to enhance combat power, while spending the money buying more expensive ships and aircraft, which then also need to be maintained, only exacerbates the problem.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x