What Hong Kong can learn from Europe’s still-evolving union

Yan Shaohua says the consensus-building project that is the European Union offers good pointers for our divided city

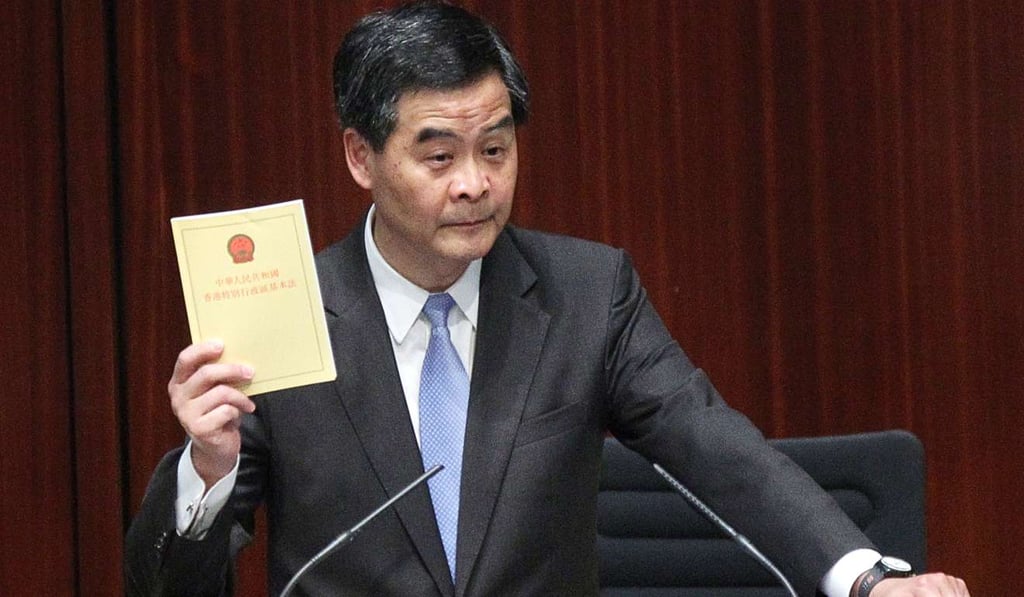

On another continent, and just one day before the chief executive election here, the European Union will celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome that laid the foundation of the union.

The EU and Hong Kong may seem very different from one another, but if we look deeper, the two could be familiar strangers. Philosophically, the EU’s concept of “unity without uniformity” resonates perfectly with the spirit of “one country, two systems” here. And, to a large extent, both the EU and Hong Kong are “strange animals” in terms of their unique place in the global system.

There are reasons to be cheerful on Europe

Giving these commonalities, it is surprising that so little attention is paid to the EU in Hong Kong’s discussions on the future of “one country, two systems”. As a researcher in European studies in Hong Kong, I believe that a study of the EU would offer valuable lessons for our problems. These lessons can be summarised in what I call the “3Cs”: constitution, communication and consensus.

Constitution