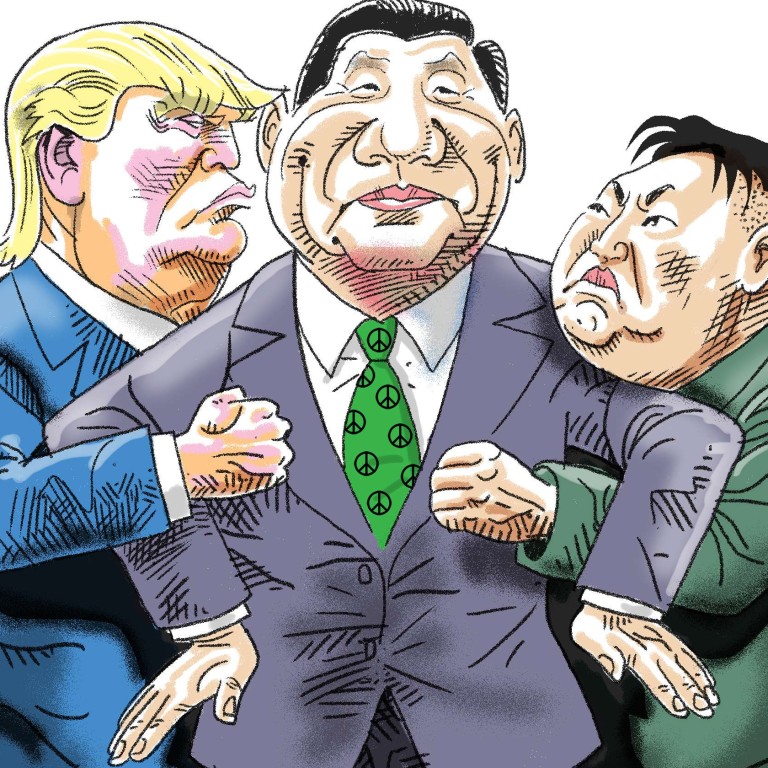

China’s role as a peacemaker on the North Korean crisis should be encouraged

Ehsan Ahrari says China’s role in easing the tensions over North Korea’s nuclear aspirations is notable, particularly when contrasted with the bluster of Donald Trump

This statement was a persuasive example of evolving global realities. The heirs of revolutionary Mao Zedong ( 毛澤東 ) are not revolutionaries. Contemporary Chinese leaders want to transform China into a new leviathan of the 21st century, a role that the United States so deftly played, especially in the aftermath of the implosion of the Soviet Union. Thus, they are resolute about avoiding a military conflict with the US involving matters that do not jeopardise their homeland or vital interests. The Korean conflict certainly does not fall into that category.

The most disconcerting variable in the current state of affairs is that the US has a new president who is not only uninformed about the intricacies of the Korean conflict, but who also refuses to use a vast body of expertise on the issue (or on any other issues of global affairs) that is readily available to him among America’s premier think tanks and security agencies.

China’s position on North Korea appears to shift

On the contrary, China is emerging as a stabiliser and a peacemaker. Undoubtedly, it is motivated to act in this manner for two critical reasons. First, if a military conflict breaks out on the Korean peninsula, China has the most to lose. In the wake of a military conflict, if North Korea were to triumph, one consequence would probably be an embarrassing defeat for China. That would permanently damage its global image as a peer competitor of the US. Besides, for China, the only war worth fighting would be if Taiwan were to declare independence from the mainland.

Trump has thrown all conventionalities of American foreign policy decision-making out of the window

Second, China has yet to size up Trump. The conventional behaviour of all modern American presidents has been to publicise their intentions and objectives towards different regions of the world through policy declarations. Trump’s three predecessors – Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama – have an impressive legacy of not taking seriously the blustery rhetoric of North Korea about turning Seoul into a “sea of fire” or “firing a nuclear-armed missile” at the White House, and leaving open the option of negotiating with Pyongyang.

Trump has thrown all conventionalities of American foreign policy decision-making out of the window in the name of discarding “politics as usual”. His decision-making style may best be described as a preference for brinkmanship and unpredictability, both of which have the potential to keep the US on the edge of war. His impulsiveness and frequent changes of mind – and sometimes making contradictory statements in the same sentence – keep even seasoned observers inside China off balance.

So, leaders in Beijing do not quite know what to make of Trump’s frequent ramblings on any given day.

The 10 minutes with Xi Jinping that changed Donald Trump’s mind on North Korea

From the US perspective, a resolution of the North Korean conflict should include Pyongyang’s agreement to unravel its nuclear weapons development, and at least slow down its ballistic missile production programme. That is the American version of an ideal solution, and is unlikely to happen. What may be achievable is that North Korea decelerates the pace of its nuclear weapons production and missile-building as a precondition for starting negotiations aimed at determining the modalities for any “next steps”. Critics may immediately say: “We have seen this movie before!” And that may be so. The chief difference this time, however, is that the US must insist on China’s commitment and uninterrupted presence in the negotiations and their ultimate outcome. There should be no backing down from that position. If China wishes to stabilise the Korean peninsula, it must also be required to commit to guaranteeing that stability by insisting that Kim Jong-un not be allowed to act like a loose cannon.

Don’t mess with Kim Jong-un, he thinks he’s his grandfather

If an agreement were to be reached on these points, it would be considered a boon, especially for China, in lowering the temperature of a potentially highly destabilising situation.

From the North Korean perspective, Kim would be afforded a new start at dialogue with both the US and South Korea for massive economic assistance, which Pyongyang needs.

However, in the wake of even minor infractions by North Korea, the US, China, South Korea and all other donors and helpers should impose tit-for-tat types of conditions on the North, especially China. This would also be the beginning of China’s advent as a global responsible stakeholder. Equally important, this has to be part of Xi’s aspirations for his country to emerge as a future superpower.

Ehsan Ahrari is an adjunct research professor at the Strategic Studies Institute of the US Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and the CEO of Strategic Paradigms, a Virginia-based foreign and defence policy consultancy. The views expressed here are the author’s own