Mind the Gap | Gentrification may be the answer to Vancouver’s drugs crisis

Programmes providing free treatment and heroin to users will only draw addicts from other parts of Canada, says Peter Guy

Canada used to be the land of frontier pioneers forged by brave immigrants like my forefathers four generations ago – all self-sufficient and self-sacrificing in the pursuit of a better life. Today, the country’s self-entitlement is the ruling principle.

No city demonstrates this more than Vancouver, where relaxed attitudes towards drug addiction and usage are translating themselves into risky economic policies and unpredictable outcomes.

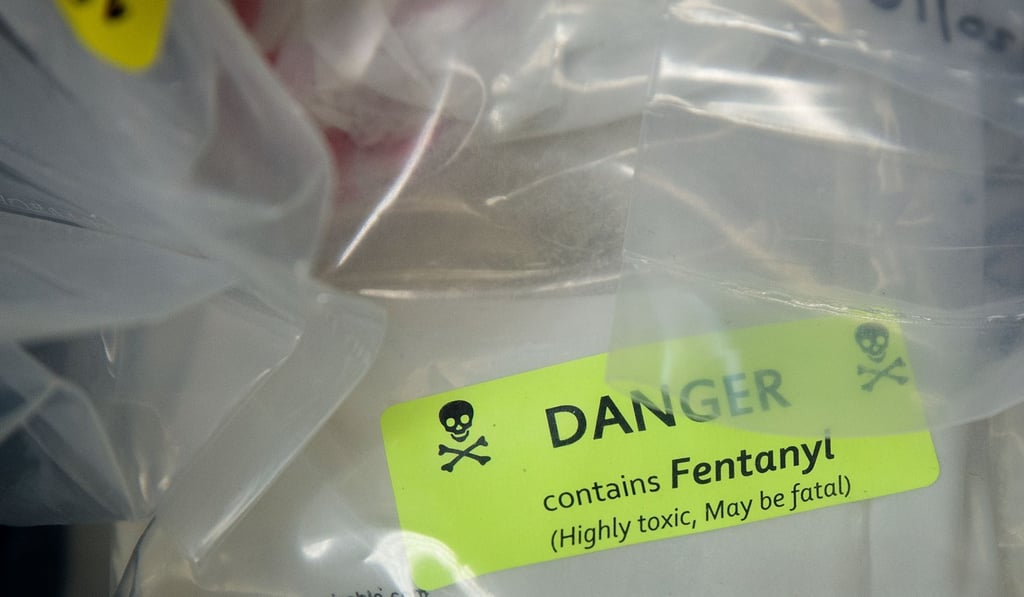

Already in the grip of a chronic homelessness crisis, Vancouver is now suffering from an opioid epidemic driven by fentanyl-laced narcotics. During the first two months of 2017, there were 219 illicit drug overdose deaths in British Columbia. That exceeds the annual average of 212 from 2001 to 2010.

The demand for more hotels as well as condominiums may just simply drive the drug problem out of greater Vancouver

Last year, there were 922 overdose deaths in BC, up from 512 in 2015 and 366 in 2014. For comparison, the number of traffic fatalities in the province in 2015 was 200.

The government and drug advocates have declared a public health crisis. Other sections of the population, especially Asians, are deeply sceptical of this progressive liberal sleight of hand and say that the fentanyl opioid problem is only a crisis among drug users and addicts.

“Vancouver East is notorious for rampant drug use, poor law and order and moral collapse,” according to an election advertisement that appeared in local editions of Chinese language dailies Ming Pao and Sing Tao last month. It represents a rare and open attack from the Chinese community on the city’s drug policies and laments Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, where addicts roam the streets like zombies from the show The Walking Dead.