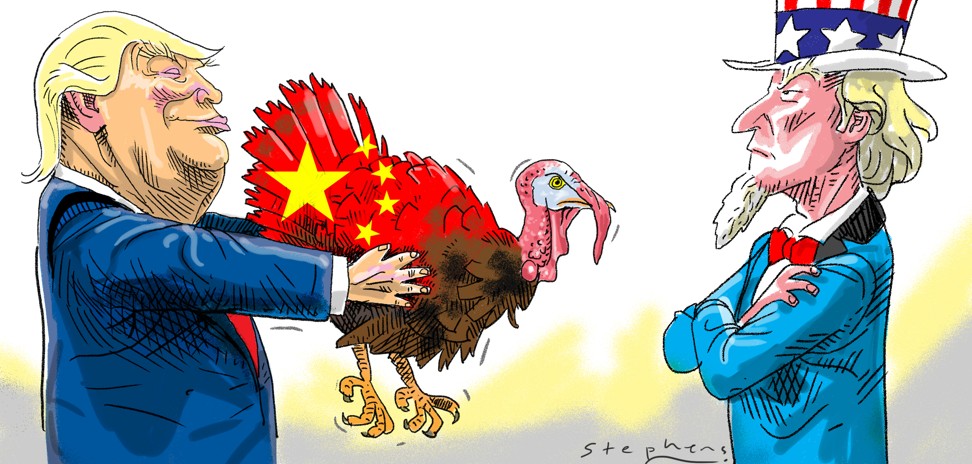

Why Trump’s trade deal with China is unworthy of America

Robert Boxwell says the US has accepted low-potential Chinese promises in a bid to close the trade deficit, especially with key bargaining chips like North Korea and the South China Sea left off the table

According to the “joint release”, as the announcement was styled, the two sides made some promises. Beijing agreed to issue guidelines to allow US-owned card payment services, like Visa and MasterCard, “to begin the licensing process”; to allow US credit ratings agencies to provide services; and to allow imports of US beef.

The US will do something vague related to exports of liquefied natural gas to China and reach “a consensus” with it to “resolve outstanding issues” for the import of “Chinese-origin cooked poultry”.

One can’t help but get the feeling that nothing has changed in the way the US does business with Beijing – accepting promises for future benefits that may or may not arrive as advertised.

Trump said of President Xi Jinping (習近平) last week: “I think he likes me a lot.” He probably got that much right.

Watch: Trump says he has developed a friendship with Xi

Access to China’s credit card market – electronic payment services – was promised over a decade ago as part of China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation.

That promise wasn’t kept then and it’s too late to make good on it now.

Beijing did not move even after a 2012 WTO ruling mandating that China do exactly what the administration is now touting as “progress”.

Chinese payment giant UnionPay essentially owns the country’s credit card market and it is too late for American companies to make a dent in it, assuming Chinese banks, the actual issuers of credit cards, will even do business with them.

Then there are the issues of trying to convince Chinese retailers to accept the cards for payment and Chinese consumers to use them instead of the mobile payment apps that about three-quarters of them are known to prefer.

Chinese debt issuers ... are hardly likely to choose an expensive US agency for their big brand

American ratings agencies are likely to face the same challenge of a tacitly closed market that the credit card companies will face.

The bestowing of AAA ratings on questionable subprime debt instruments leading up to the 2008 financial crisis aside, they generally have higher rating standards than their counterparts in Asia.

But since the glossy sheen of practically anything from the US financial sector went out with 2008, Chinese debt issuers, who pay the agencies for ratings and for periodic reviews of them, are hardly likely to choose an expensive US agency for their big brand.

Not that that’s going to happen tomorrow anyway. The joint release only stated that China will allow foreign firms “to provide credit rating services, and to begin the licensing process for credit investigation”.

How they will do the first without the second is anyone’s guess.

US beef sales to China were banned in 2003 in the wake of an outbreak of mad cow disease. Getting back something that was suspended reasonably but then prolonged for over a decade is hardly an example of the art of the deal, especially since it was the administration of Barack Obama that really did the work.

The joint release also states that the two countries are working towards a consensus to provide US market access for Chinese sellers of cooked poultry.

The only possible “consensus” related to this issue is that few in the world trust mainland Chinese food standards.

Mixed results from Donald Trump’s first 100 days

Finally, the statement about liquefied natural gas sales to China is simply fluff: “The US welcomes China, as well as any of our trading partners, to receive imports of LNG from the US.” There’s little point parsing that sentence for meaning.

Closing the trade deficit by selling [US] natural resources at cost to China is shameful

LNG prices are currently several times higher than that of Chinese domestic coal, essentially LNG’s primary energy competitor and which requires no foreign currency, a fact that Chinese buyers like to point out when negotiating with foreign LNG suppliers.

American LNG suppliers, sitting down for interminable haggling sessions with mainland Chinese buyers – which is frequently what happens in LNG sales – will have a hard time competing with suppliers from the Middle East and Southeast Asia, whose costs are significantly lower.

If helping to close the trade deficit with China means selling LNG at razor-thin profits or none, what’s the point?

Closing the US trade deficit by selling natural resources at cost to China is shameful.

Announcements like the one last week make the US look like a developing country, touting trade deals to sell commodities like beef and LNG, and look naive, touting progress in financial services that are likely to mean little to American companies.

None of the components of this “early harvest” look like they will do much to create jobs or otherwise make the US more competitive, essentially the promise that carried Trump into the White House.

Also, the whole notion of somehow coming to a friendly agreement on trade without resolving the strategic issues of Beijing’s relationship with North Korea and its building of artificial islands in the South China Sea – which Beijing, unsurprisingly, doesn’t want to do – eliminates some of the leverage the US administration might otherwise have had if it did not see satisfactory movement on those issues.

Trump talked long and loud on the campaign trail about getting tough with China. If getting some low-potential promises and giving up a substantial lever of persuasion vis á vis important strategic issues is his idea of “winning”, the US is in a lot of trouble.

Robert Boxwell is director of the consultancy Opera Advisors