Can Hong Kong’s leaders show the resolve to spare country parks and build on brownfield sites instead?

Michael Lau and Douglas Anderson say an environmentally risky focus on developing country parks and reclamation is inexplicable, when brownfield sites provide the perfect building sites

After the severe acute respiratory syndrome crisis in 2003, city dwellers reintroduced themselves to Hong Kong’s green lungs. And they breathed deep. The appreciation and love of our country parks runs in the DNA of Hong Kong people. People just know that they are good for the city, good for the public and good for our environment.

The debate on whether natural areas should be sacrificed to address Hong Kong’s housing crisis has heated up again. We want to pour icy cold water from the waterfalls of Mui Wo on the notion that this is a viable development option.

Hong Kong land supply situation remains of ‘great concern’, think tank says

There is a wide consensus in society that Hong Kong is facing an imminent housing crisis. So we should address the problem with hard facts. As tens of thousands wait for a chance to occupy a public housing flat or overpay for a shoebox-sized private one, we appreciate the aspiration of families for a safe place to live and raise a family.

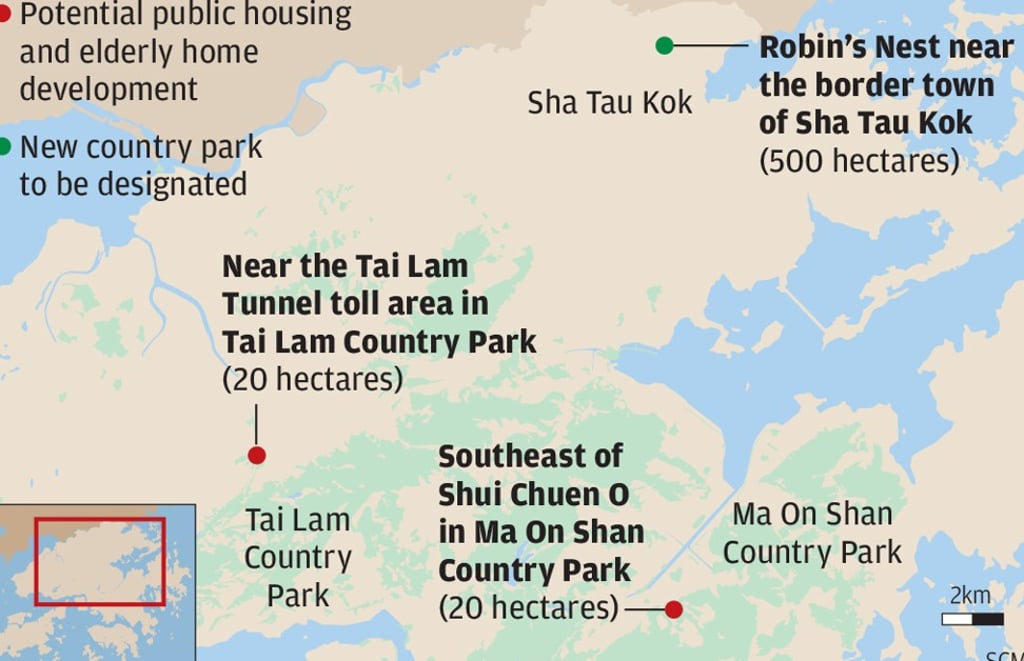

But why do people want to target our country parks, when more suitable land lies close to our new towns and transport systems – land that is underutilised, poorly planned and causing environmental problems?