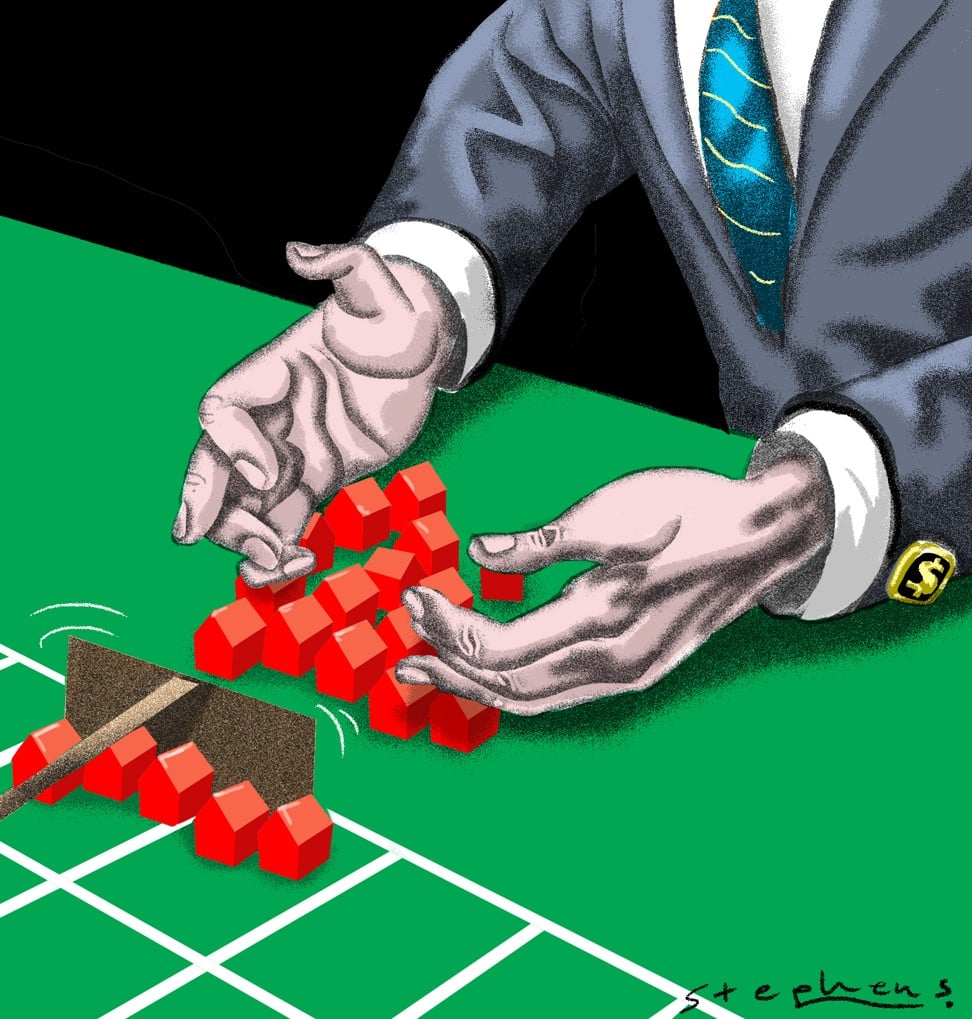

Hong Kong needs radical tax reform, as addiction to real estate is hurting long-term growth

Stefano Mariani says using fiscal policy to reduce the attractiveness of property speculation would encourage investment capital to flow into other sectors, and channel much-needed funds into the knowledge-based economy

The focus of reformists in our Legislative Council, however, should not be on raising taxes, but on broadening the tax base.

One of the underlying fiscal reasons for the property bubble is that, since the abolition of estate duty in 2006, capital assets are generally not taxed. This means investors can hoard real estate and realise very large capital gains, tax-free.

Investors can hoard real estate and realise very large capital gains, tax-free

Hong Kong currently has an unbalanced tax code, which taxes the means through which social mobility may be achieved – that is, income from a successful business or a well-paying job – but leaves capital and accumulated wealth untouched. The effects of this are compounded by the absence of legal restrictions on the acquisition of residential property by non-permanent residents, in stark contrast with jurisdictions operating under similar space constraints, like Singapore and the Channel Islands. Non-permanent resident speculators, therefore, hold an indefensible tax advantage relative to locals.

The government’s strategy of simply hiking stamp duty rates has largely been unsuccessful in cooling the market, an outcome that, to a tax practitioner, is unsurprising.

First, many Hong Kong properties are enveloped, meaning they are owned by offshore companies, not directly by individuals. When the owner of the company wishes to sell the property, he simply sells the shares in the company and that transfer does not bear stamp duty.

Second, high rates of stamp duty increase transaction costs, driving owners to wait for still greater capital appreciation, and accordingly does nothing to reverse the hoarding of property by wealthy non-permanent residents.

CY Leung seeks to plug housing loophole with stamp duty rise for multiple flat purchases

Stamp duty is only a partial solution. It must be complemented by taxes that seek to charge both pure economic gains realised from real estate speculation, and actively discourage the holding of vacant properties.

The solution is straightforward: introduce a limited capital gains tax on residential property and an annual tax, calculated as a percentage of the market value of all vacant or unlet properties held by non-permanent residents.

Immovable property speculation does little to contribute to the ‘real economy’

An annual tax would make the holding of Hong Kong residential property an ongoing liability for non-permanent residents and so generate commercial incentives for investors to divest their stock. It would further provide the public purse with a steady revenue stream. This tax, because it would be levied on an annual basis, would by its nature be less cyclical than stamp duty, which is only charged when there is a transfer of property.

That is because immovable property speculation does little to contribute to the “real economy”: it is not conducive to industrial diversification, does not sustainably stimulate local employment, and does not foster the development of a highly skilled local workforce.

Hong Kong slips to new low in innovation rankings

If we are to claim the cutting edge of innovation from Singapore and South Korea, we must wean ourselves off our real estate addiction.

Indeed, using fiscal policy to decrease returns on property speculation should encourage the reallocation of investment capital to other sectors and, in particular, channel much-needed funds into R&D and innovation.

The tax reform model I have outlined is therefore complementary to the government’s efforts to promote a knowledge-based economy.

Put another way, tax policy is as much stick as it is carrot. Fiscal sweeteners such as tax incentives for R&D, aircraft leasing, and the like, are in principle helpful, but more needs to be done to persuade investors that there is a commercial case for stepping into the higher-risk arena when there are currently low-risk, high-yield returns to be had in real estate speculation.

In the longer run, policymakers should look beyond property taxes, and begin to evaluate whether the tax code as a whole warrants modernisation. Ideas of interest include the introduction of a tax on remitted income or, specifically, remitted dividends.

Singapore, for example, whose revenue law code is very similar to our own, taxes income sourced outside of the city and then received in it. Our Inland Revenue Ordinance, broadly speaking, only taxes locally sourced income. Adapting a Singaporean model of income taxation might, for example, tax offshore dividends received by individuals in Hong Kong and so eliminate the asymmetry between a salaried worker, who pays salaries tax on his income, and the owner of an offshore company generating profits elsewhere, who would currently receive dividends tax free.

It is incumbent on the government and Legco to take a courageous and unblinkered approach

Nevertheless, the objective of comprehensive tax reform should be to resolve the age-old structural problem of our narrow tax base: a majority of Hong Kong residents pay no tax at all. Because we are such an unequal society, a broad-based – and probably regressive – tax like a goods and services tax (otherwise known as VAT or GST) is not at this stage advisable.

Taxing a broader range of assets and income streams should, on the other hand, go towards meeting the government’s future funding needs with a view to improving the quality of life for the poor, young families, and the elderly, and also manage any upward pressure on our current tax rates. Hong Kong must retain its low headline tax rates, especially in view of the international trend of cutting corporate tax.

If, however, increases in public expenditure are to be funded and social harmony restored, it is incumbent on the government and Legco to take a courageous and unblinkered approach to radical tax reform.

Stefano Mariani is a lawyer and revenue law specialist, who has published widely in the field of taxation. The views expressed in the article are solely those of the author