Unlike Nato, the SCO needs no enemy to justify its existence

Zhou Bo says a comparison of the two groupings, both of which welcomed new members this month, shows up the limits of the transatlantic military alliance

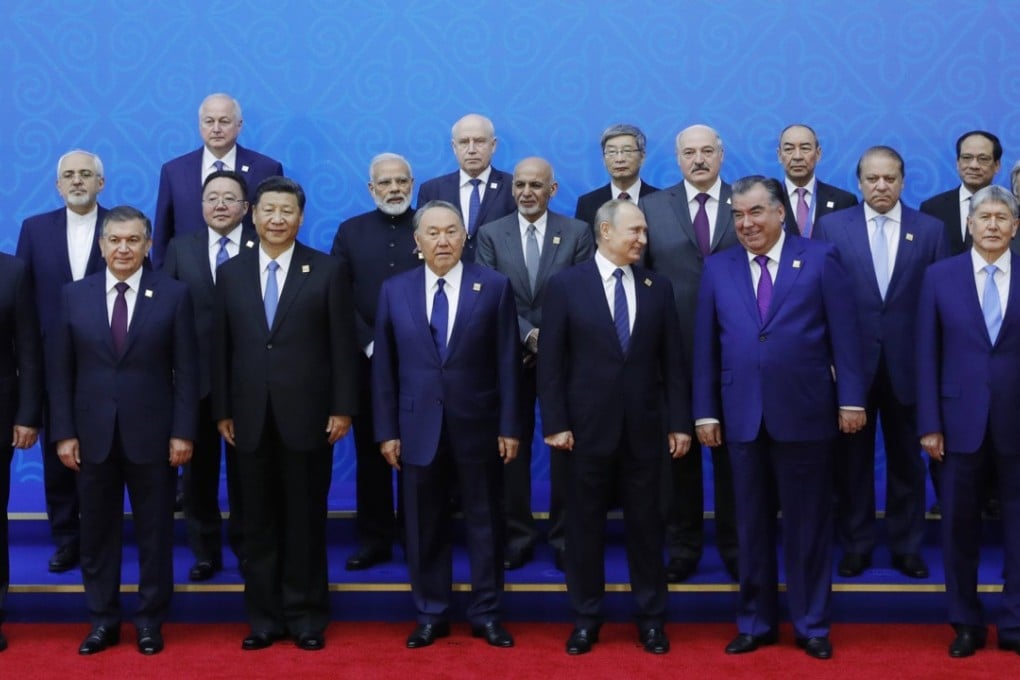

Nato is expanding faster. When Montenegro joined the alliance on June 5, it was only eight years ago when Albania and Croatia became member states. By comparison, India and Pakistan’s entry into the SCO is just the first such enlargement since the organisation was founded in 2001. But the SCO wins for size: it now has a quarter of the world’s population and covers three-fifths of the Eurasian continent.

Nato has an intrinsic problem. As a military alliance, it needs enemies to justify its survival. What united the alliance during the cold war was the Warsaw Pact led by the Soviet Union; now it is Russia and, most recently, Russia and Islamic State. At the Nato summit, UK Prime Minister Theresa May placed Russia in the same category of threat to the West as IS.

Trump castigates Nato allies for weak defence spending

How much further Nato can go remains to be seen. Nato lives on the fear of the central and eastern European countries of Russia, but it has tried its best to eschew a direct Nato-Russia confrontation, in spite of its protest of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and military intervention in Ukraine. Its acceptance of Montenegro, a small country with fewer than 2,000 troops, looks more like picking a low-hanging fruit.

The SCO, by contrast, is not designed to address an external threat, so it is not directed at the West. It looks inwards to address its own problems. Its predecessor, the “Shanghai Five”, succeeded in resolving border disputes among China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan. Today, its security concern remains uprooting the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism and religious extremism. No one is sure when this can be achieved, but sincere efforts are being made. In 2004, an SCO counterterrorism centre was established in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Since 2002, all military exercises within the SCO have been on counterterrorism.