How oil made Donald Trump turn his back on Paris climate accord

Robert Delaney says US President Donald Trump and his administration’s efforts to stymie climate change action, and focus on protecting US oil and coal producers, stem from a desire for self-preservation

Dozens of flights in the US southwest cancelled because the air is too hot to allow some planes to take off. Recreational islands near Toronto submerged, forcing businesses to close for good. Tidal flooding in residential areas of South Florida, even in the absence of stormy weather. These are just a few recent examples of extreme weather in North America. All of them disruptive, costly and unprecedented in scale, at least within the time frame of recent history.

Yet no scientist can say conclusively that these are a result of industrial activity pushing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, as Nasa points out, higher than they have been in the past 400,000 years.

Because of this inability to provide irrefutable proof, and amid concern about the jobs threatened by efforts to rein in carbon dioxide emissions related to the burning of fossil fuels, President Donald Trump and his administration said they have prioritised the economic health of coal and oil producers.

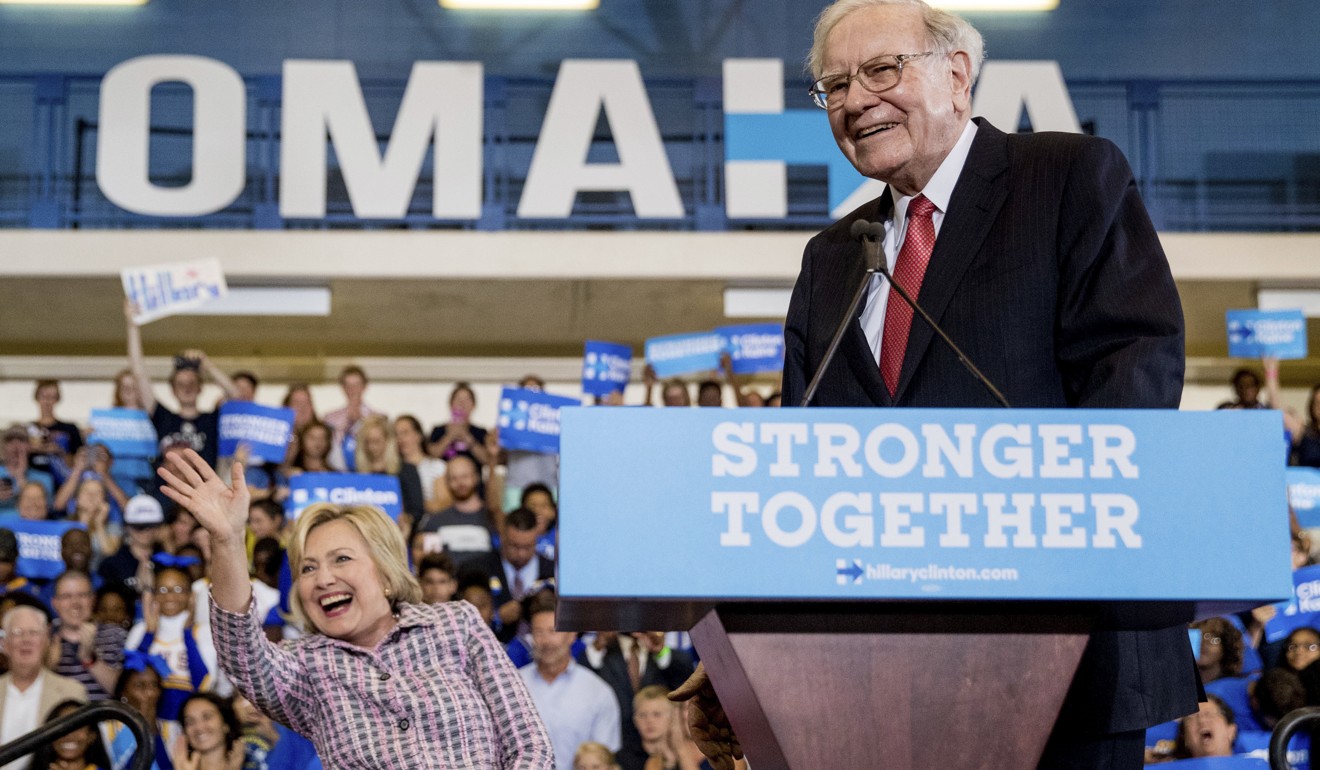

Let’s look at the issue from a different perspective. Trump has few enthusiastic supporters among US billionaires. Warren Buffett, Michael Bloomberg, and Apple CEO Tim Cook all supported Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election. Tech billionaire Peter Thiel emerged as a financial backer, but the extensive coverage of that was notable only because it stood in stark contrast to the very vocal anti-Trump sentiment in Silicon Valley.

Trump needs the political network controlled by Charles Koch and his oil-refining empire

Appointing the EPA’s biggest opponent to direct the organisation showed the lengths Trump will go to

The publication of emails in February, shortly after Trump appointed Pruitt as EPA chief, revealed regular contacts between Pruitt in his former position as Oklahoma’s attorney general, and Koch-funded groups. Appointing the EPA’s biggest opponent to direct the organisation showed the lengths Trump will go to, to protect oil and coal companies.

Trump’s game is clear. Efforts to stymie climate action stem less from uncertainty around climate science and more from self-preservation. If ongoing investigations into his team’s connections to Russian attempts to influence the presidential election turn up hard evidence, he’ll need all the support he can muster.

Watch: Washington Post reporter stands by story on Trump and Russians

But the efforts to cast doubt on scientific consensus, aided by Koch, will continue, because this provides cover for his political survival strategy. The Washington-based Cato Institute, for example, regularly tries to debunk the consensus reached by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, that human burning of fossil fuel has been the prime driver of higher global temperatures over the past century.

On May 25, just days before Trump’s Paris accord announcement, a Cato opinion piece, titled The Scientific Argument against the Paris Climate Agreement, argued that, “the maximum warming caused by humans is somewhere between 0.4 and 0.5 degrees Celsius – half of the total since the industrial revolution”, directly refuting IPCC conclusions.

Cato has published many reports in recent years critiquing the IPCC’s methodology; all written in a way that’s easy for someone without scientific training to understand and just a Google search away. But the basic problem in weighing Cato’s conclusion against the IPCC’s is that it is a choice between a partisan think tank with libertarian leanings, and a panel of more than 830 authors and reviewers from over 80 countries, selected for their scientific expertise. The other problem with Cato: it was founded by Charles Koch.

Robert Delaney is a US correspondent for the Post based in New York