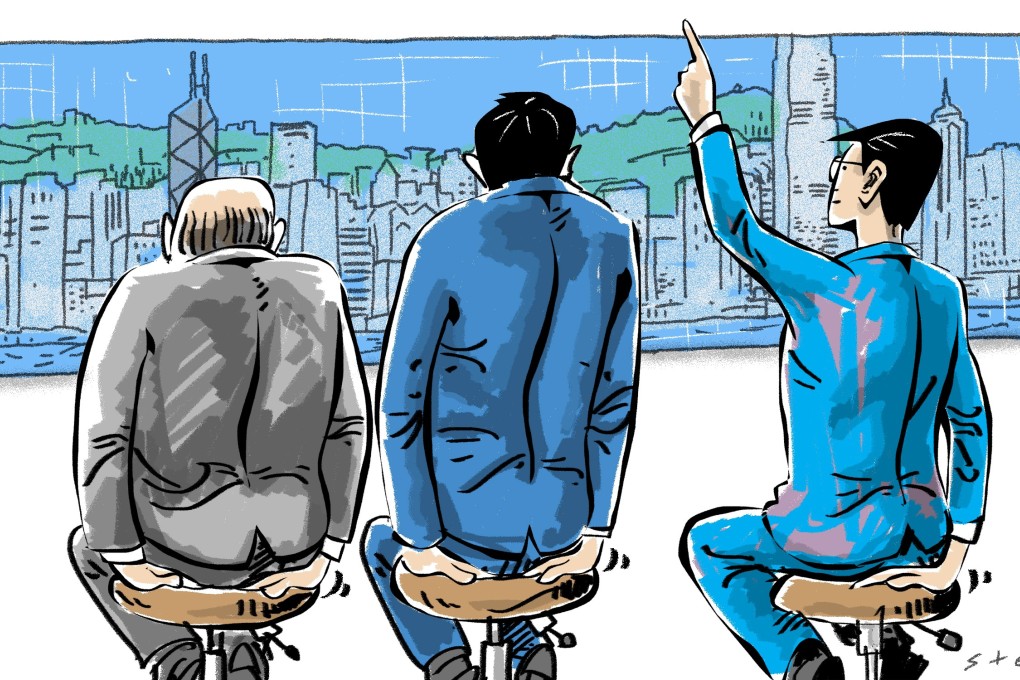

Can Hong Kong become indispensable to the nation again?

Lawrence J. Lau says 20 years after the handover, it’s time to abandon the policy of positive non-interventionism as the economic and social challenges facing the city cannot be solved without long-term planning and coordination

The transition itself went smoothly under the leadership of Tung Chee-hwa, the first chief executive of the Hong Kong special administrative region. However, soon after, East Asia was engulfed by a currency crisis, leading to widespread devaluation and economic recession everywhere (and the bursting of the housing bubble in Hong Kong). This was followed by the outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003, the 2008 global financial crisis and the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis, which all affected the economy negatively.

Hong Kong, ever so resilient and resourceful, survived all these crises. Today, the city remains ahead of South Korea and Taiwan in real gross domestic product per capita, but behind Singapore. The most significant change is the decline in the size of Hong Kong’s GDP relative to the mainland’s – it went from 8.7 per cent to just below 3 per cent, and on a per capita basis from 16.6 times to only 5.6 times.

However, during the past two decades, income inequality in Hong Kong has risen sharply, as has the cost of housing, which doubled between 1997 and 2016. A significant proportion of Hongkongers live in tiny, substandard, illegally subdivided rooms, which are a major fire hazard.

Politically, Hong Kong has not fared so well. The “one country, two systems” principle has been widely misunderstood. It is meant to be a single country, but with one part, the mainland, operating under the socialist economic system and the other part, Hong Kong and Macau, operating under the capitalist economic system. It is not meant to be two different political systems. Whatever happens to the “two systems” in 2047, it will always be “one country”. It is therefore essential to embrace the idea of “one country”, even if one does not support the current policies of the central or the Hong Kong government.