Why Hong Kong’s justice minister Rimsky Yuen is so sanguine about joint checkpoint for express rail link

Jason Y. Ng says the logic behind Rimsky Yuen’s support for immigration co-location at West Kowloon is unsound, but the justice minister’s confidence stems from knowing that Beijing always has the last word

The central question is a straightforward one: is the joint checkpoint proposal constitutional?

The answer can be found in Chapter II of the Basic Law, which governs the relationship between mainland China and Hong Kong. Articles 18 and 22 prohibit national laws from being applied in Hong Kong (with the exception of matters relating to defence and foreign affairs) and forbid Chinese authorities from interfering in the special administrative region’s affairs.

The pros and cons of different solutions to Hong Kong’s express rail checkpoint issue

In addition, Article 19 grants Hong Kong courts exclusive jurisdiction over cases that occur anywhere within the territory. That means any attempt to enforce Chinese law on Hong Kong soil – no matter the location or size of the area – is on the face of it in breach of at least three provisions of the Basic Law.

Watch: Carrie Lam inspects new high-speed train

But the government begs to differ. Secretary for Justice Rimsky Yuen Kwok-keung has so far put forward two counter-arguments. First, he argues that the designated areas, once leased to the central government, will no longer be part of Hong Kong’s territory and therefore outside the jurisdiction of the Basic Law.

Yuen’s argument is plainly circular: it is constitutional to carve out certain areas because those areas have been carved out of the constitution. If that were true, then by analogy there would be nothing to stop the government from excluding, say, left-handed people from the protection of the Basic Law, on the basis that those people will have no such protection once they are excluded.

Second, Yuen invokes Article 20 of the Basic Law, which allows the Hong Kong government to enjoy new powers conferred to it by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee.

Bending that provision to serve his purpose, Yuen argues that the SAR government can seek a “new power” from the Standing Committee, so that it can in turn authorise the mainland authorities to enforce national laws in the designated areas.

In essence, Yuen is asking Beijing to give Hong Kong the power to give Beijing the power to do what Beijing doesn’t currently have the power to do in Hong Kong. Mr Secretary should get an “A” for creativity and an “F” for logic.

Such illogic aside, many are asking how constitutional lawyers have got comfortable with seemingly similar arrangements enjoyed by foreign consulates and “mainland-controlled” areas like the central government’s liaison office in Sai Ying Pun and the People’s Liberation Army garrison in Tamar.

Mr Secretary should get an ‘A’ for creativity and an ‘F’ for logic

Foreign consulates are specifically dealt with in Annex III to the Basic Law, which imports Chinese regulations governing diplomatic privileges in compliance with the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. Even so, consuls and their staff only enjoy diplomatic rights and not law enforcement powers. What’s more, Hong Kong courts still have full jurisdiction over any illegal acts committed on those premises. The same is true for the liaison office and the PLA garrison.

If the joint checkpoint proposal violates the Basic Law, the next question becomes: are there less invasive alternatives?

Commentators and advocacy groups have tabled a number of options. One of them is to limit the mainland officers’ powers to the performance of immigration and customs controls only, instead of the full criminal and civil jurisdiction currently being proposed.

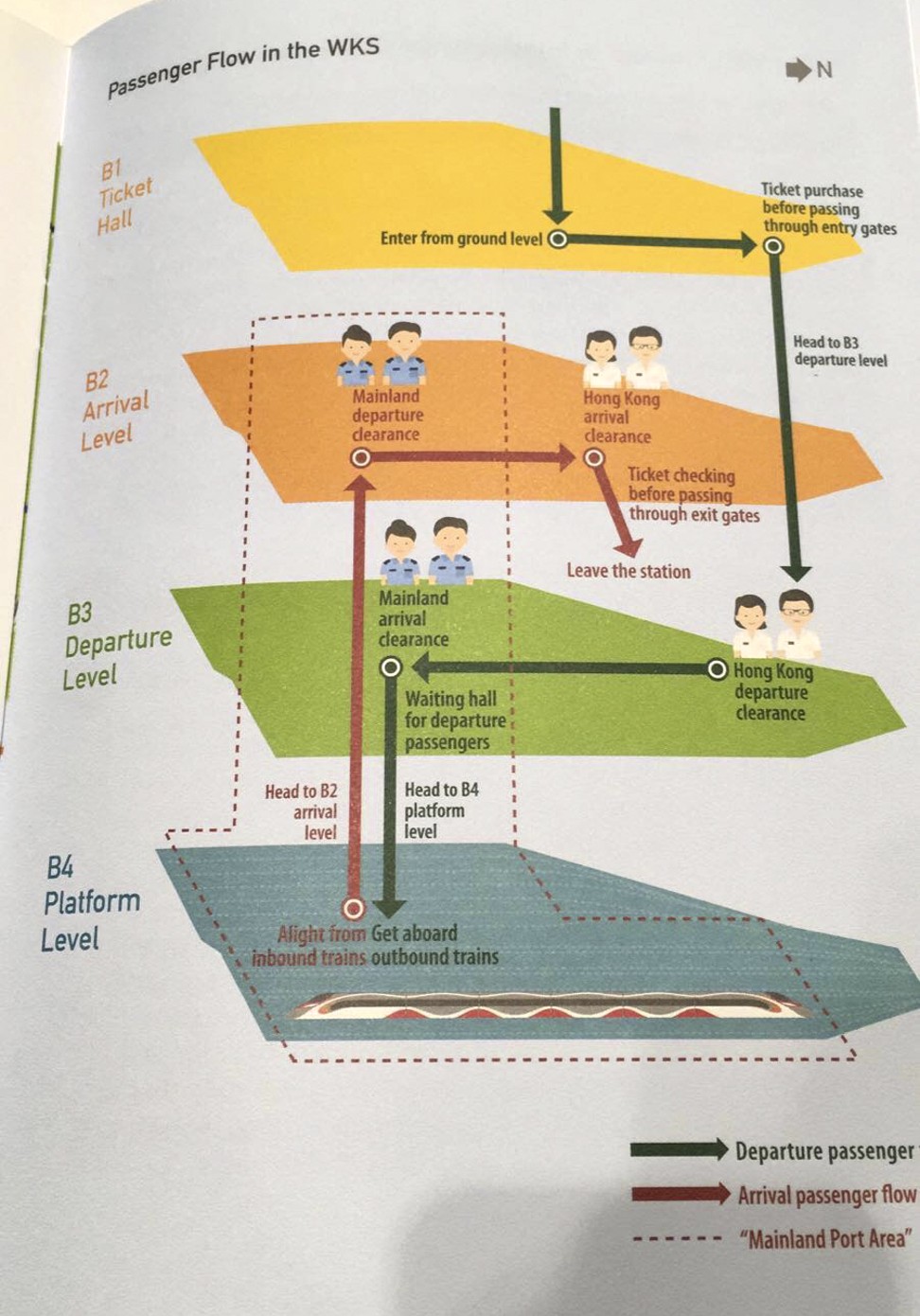

The most legally viable alternative so far is one that involves a combination of ground and on-board clearance procedures. Based on the current rail network, high-speed trains leaving West Kowloon must make a first stop in either Shenzhen or Guangzhou. Under the “combined approach”, Hong Kong passengers whose final destination is one of those two cities will exit the train and go through a physical checkpoint upon arrival. Those who continue their journey to other destinations will stay in their seats and await immigration officers to check their documents and luggage on board.

On-board clearance is typical in Europe and does not cause any travel delay to passengers. However, this approach will incur additional expenses on the mainland side by requiring physical checkpoints to be set up in Shenzhen and Guangzhou.

Therein lies the conflict of interest: mainland authorities see no reason why they should bear any of the cost of linking Hong Kong to their massive high-speed rail system. Hong Kong citizens are the ones who need to figure things out for themselves.

It is again the citizens of Hong Kong who will pay the price – in dollars and in dignity

In the coming months, legal experts and government officials will continue to argue over the legality of the joint checkpoint proposal. Already, at least two judicial reviews have been filed to challenge it in local courts. Whereas complicated legal issues may be of little interest to the majority of citizens who prize convenience and connectivity above constitutional principles, they matter even less to the SAR government.

That explains the justice secretary’s confidence in the rail plan. He, too, knows that no matter what unsound arguments he puts forth, Beijing will always have the last word. But each time the Standing Committee uses its trump card, it chips away at the authority of the Basic Law and makes the “one country, two systems” promise mean a little less. And it is again the citizens of Hong Kong who will pay the price – in dollars and in dignity.

Jason Y. Ng is an author of several books on Hong Kong and a member of the Progressive Lawyers Group