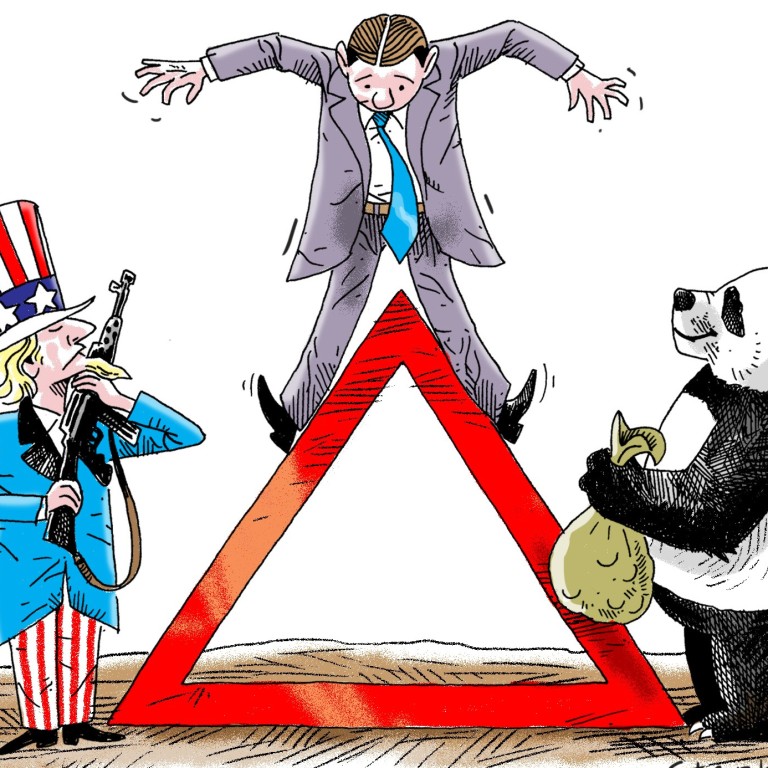

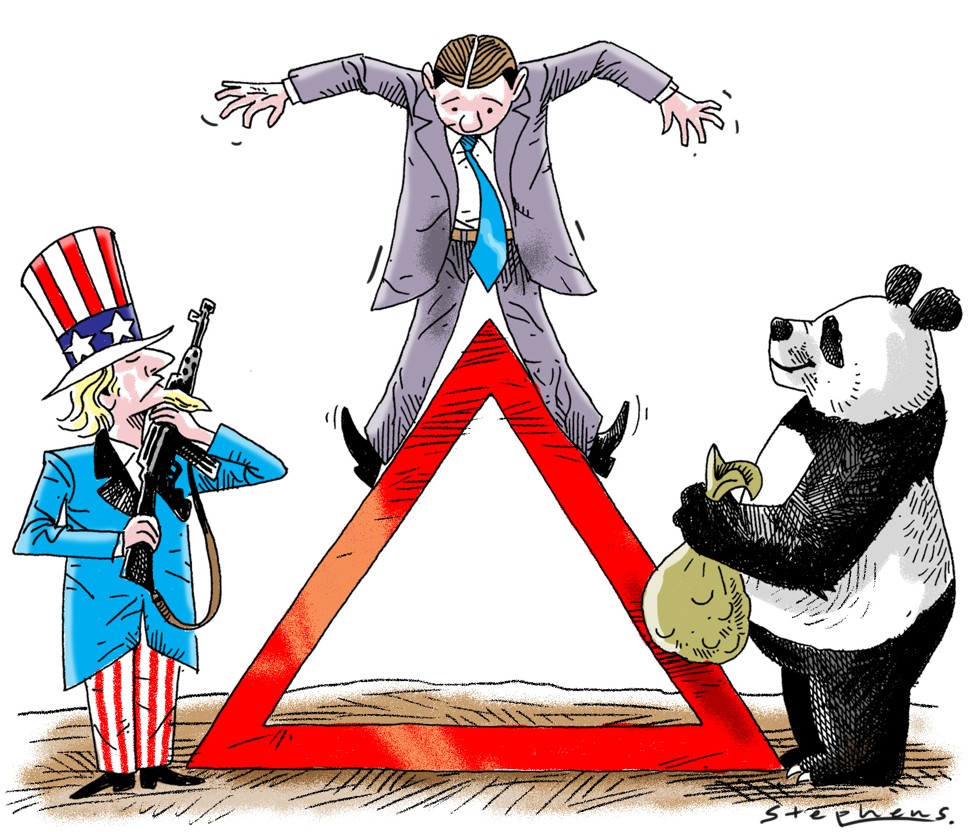

China’s cash and American troops are inspiring fine balancing act from US allies in East Asia

David Zweig says China’s economic clout and America’s security commitments are factors as Australia, South Korea and the Philippines try to keep both world powers on their side

How they balance those ties will greatly affect the shape of the region in the coming years.

The American corner exudes military strength, as the US “hegemon” remains the key ally of many countries in the region. Some alliances, established in the 1950s, survived the collapse of the Soviet Union. So, while the US remains an important economic partner for the region, its primary function is to protect its allies from external threats. Even Vietnam, Myanmar and Indonesia, who are not America’s security allies, see US ties as a hedge against China.

Australia’s dependence on China’s economy is astonishing

As well, Australia’s dependence on China’s economy is astonishing. In 2016, nearly 33 per cent of exports went to China, far more than any other major country in the region. Chinese purchases of raw materials shielded Australia from the 2008 global financial crisis. A powerful business lobby supports China, while shifts in Chinese gross domestic product directly affect key Australian companies and their stock prices. Not surprisingly, some Australian officials have expressed somewhat pro-China positions that are at odds with US perspectives.

Just as the Howard government gave China one of its key global goals, “market economy status”(Australia is the only US ally to have done so), in 2013, prime minister Julia Gillard established a renminbi-Australian dollar swap mechanism that treats the renminbi as a reserve currency, weakening the US dollar. Her defence white paper did not mention China as a military threat to Australia or the region. In line with Australia’s debate over its “China choice”– accommodate China’s rise or join the US in containing it – in 2013, foreign minister Peter Varghese said: “China has every right to seek greater strategic influence to match its economic weight”, and that peace will depend in part on “the extent to which the existing international order intelligently finds more space for China”. Still, Australia remains committed to ANZUS.

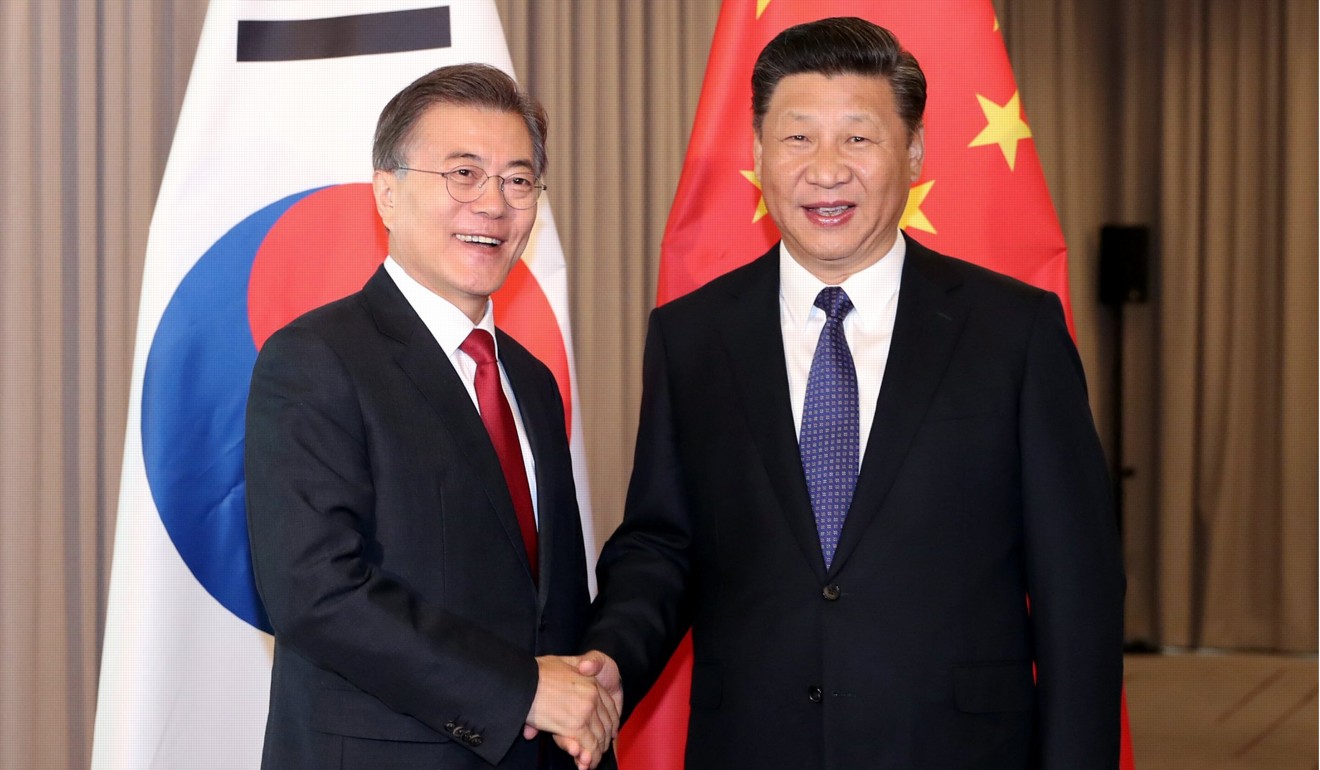

China’s use of its economic power to punish South Korea for trying to enhance its own security has backfired

But last year, China was South Korea’s largest trading partner, taking 25.1 per cent of its total exports. China is a key source of tourists for Korea, while Koreans form the largest contingent of foreign students in China. And Korean enterprises ship cheap goods manufactured in China back home.

Events in the Philippines have been the most quixotic. Then president Benigno Aquino, a stalwart supporter of US security ties, responded to Obama’s “pivot” by giving the US access to five airfields, several of them a short jump from reefs claimed by China in the South China Sea. In 2014, with strong US support, he challenged China’s claim to much of the sea at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, ratcheting up his face-off with China.

However, although Philippine dependence on China’s economy lags well behind the other two states – exports to China are only 10.8 per cent of the total – economic opportunities presented by improved China ties are enhancing relations.

Philippines drops tough talk against China to hail new era of economic ties

While Manila’s military and foreign affairs bureaucracy prefer strong links with America, expanded trade and investment, and a more moderate Chinese position on its territorial disputes with the Philippines, could further weaken Philippine relations with the US.

Duterte obtains dual defence support from China, US

Clearly, China’s economic clout and America’s security commitments are factors, as these states balance ties with both powers.

Nevertheless, leadership changes shift each state’s position within the triangle. Who governs Australia shapes the country’s “China choice”. In South Korea, shifts between leftist and rightist leaders, whose strategies towards the threat from the North differ, best explain how it manages relations with the two world powers. Finally, Duterte’s dislike of America and his desire to enhance domestic economic growth has triggered a massive redirection in the Philippine-US-Chinese triangle.

David Zweig is chair professor of social science and director of the Centre on China’s Transnational Relations at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology