China must get along with regional powers to make its New Silk Road plan work

Raffaello Pantucci writes that Beijing is seeking to increase its presence in regions where it is going to need more friends than enemies, including India

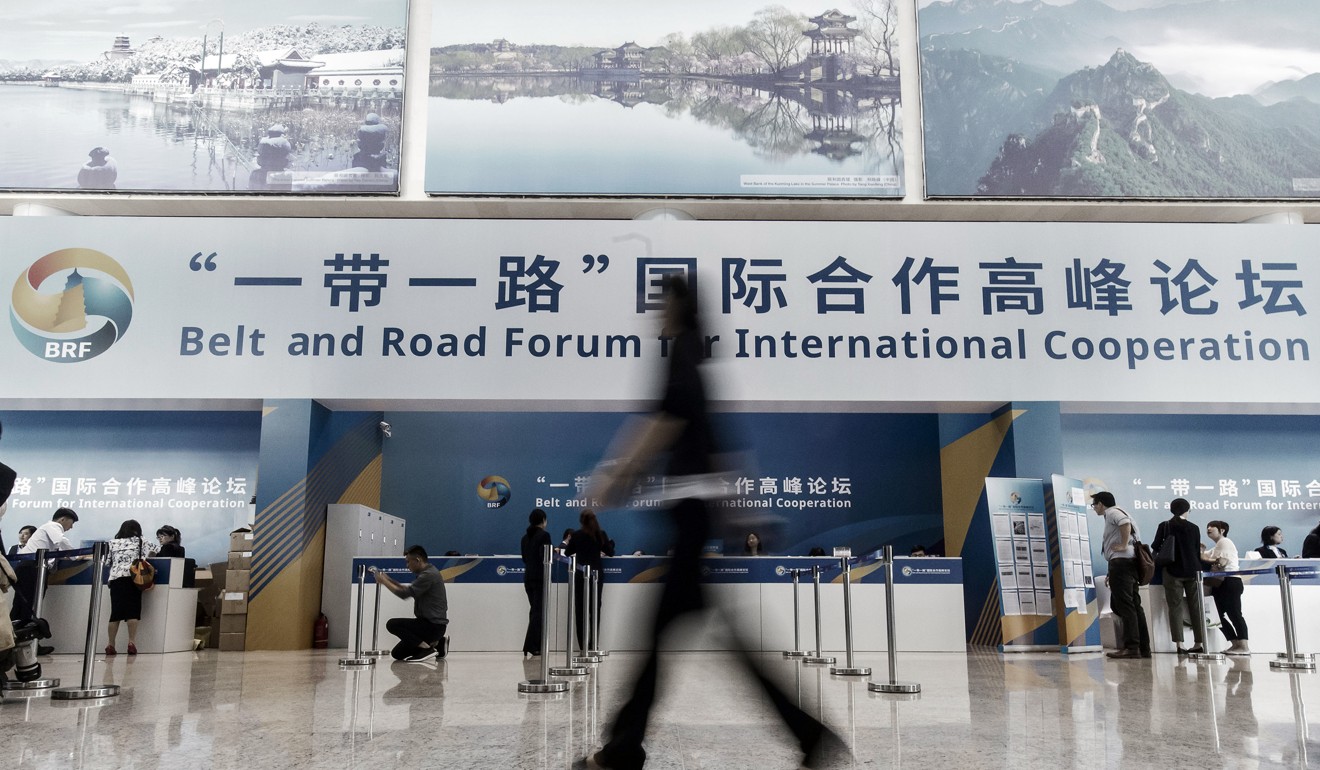

Geopolitics matters. As we move deeper into a multipolar world, the importance of grand strategy will only grow. Relations between states at a strategic, economic and even emotional level will all intertwine to create a complicated web that will require sophisticated diplomacy to navigate. For China this is a particularly important lesson to learn, given its keynote “Belt and Road Initiative” that requires an acquiescent and peaceful world to deliver on its promise of building a web of trade and economic corridors emanating from China and tying the Middle Kingdom to the world. China’s current stand-off with India highlights exactly how geopolitics can disrupt Xi Jinping’s foreign policy legacy initiative.

The details of the specific transgression within this context are not entirely important. China is asserting itself in its border regions and changing facts on the ground to solidify claims. Indian push-back is based on strategic relations with Bhutan that go back a long way and a concern about how this changes Indian capabilities on the ground.

It comes at a time when relations between China and India are particularly low, with suspicion on both sides. Most analysts do not seem to think we are going to end up with conflict, but it is not clear at the moment what the off-ramp looks like. But whatever this exit looks like, we are undoubtedly going to see China finding it tougher to advance its Belt and Road Initiative through India’s perceived or real spheres of influence in South Asia.

This is something which is already visible in the broader tensions between China and India over Pakistan. China has focused on the country as a major ally that it is supporting to develop its domestic economy and improve its strategic capacity for a variety of reasons. Yet this approach directly undermines Pakistan’s perennial adversary India’s current approach of isolating Islamabad on the international stage as punishment for cross-border terrorism.

Further, the CPEC route’s cutting through disputed territories in Kashmir provides a further spur to Indian concerns. At a more tactical level, China’s refusal to allow Jaish-e-Mohammed leader Masood Azhar to be included on the list of proscribed terrorists, and its blockage of Indian entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group, all point to a relationship with which Beijing is clearly playing an aggressive hand. India has also shown itself to be a hardball player in this regard, making public shows of proximity to the Dalai Lama, a source of major concern to China.

Of course, such a posture is either capital’s prerogative. Past relations between China and India have been fraught. The two countries have fought wars against each other. Yet at the same time, the overall tenor between the two is often in a different direction: both are proud members of the BRICS grouping (arguably the two leaders of it), and both have embraced the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. India is keen to gain a slice of the outbound Chinese investment, while China is keen to access India’s markets. Both see the opportunities and recognise that as Asian giants they have an upward trajectory over the next few decades. Together they will undoubtedly be stronger than alone.

But this positive message is thoroughly buried under the negative news around the border spat in Bhutan. Rather than being able to build a productive relationship, the two countries now find themselves at loggerheads. This is a problem for both, but has an important lesson within it for China as it seeks to advance its Belt and Road Initiative globally.

To be able to credibly realise the Belt and Road Initiative, China is going to need to have positive relations with partners on the ground, in particular major regional powers.

To be able to credibly realise the Belt and Road Initiative, China is going to need to have positive relations with partners on the ground, in particular major regional powers. With plans to build infrastructure, expand investments and grow physical footprints on the ground, Beijing is seeking to substantially increase its presence in regions where it is going to need more friends than enemies. When looking across South Asia, this means having a productive relationship with India. Without this, Delhi will find ways of complicating China’s approach or, more bluntly, obstructing it. Given the importance of some of the South Asian routes to the development of some of China’s poorest regions, it is important for Beijing to make sure that these corridors related to the Belt and Road plan live up to their promise.

And this lesson is one that will be relevant outside a South Asian context. For Beijing to be able to deliver on the promise of the Belt and Road Initiative, it is going to need to watch the geopolitics. Similar problems may eventually materialise with Russia, or on the seas as Beijing seeks to turn the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road into a reality.

Without friends along these routes, China is going to find it very difficult to make these visions work no matter how much money they try to throw at the problem. With nationals, companies and interests broadening and deepening, China needs an acquiescent environment and countries that are eager to work with it. Geopolitics is a chess game of many different levels, and as power becomes more diffuse on our planet, Beijing is going to have to learn how to play these games if it wants to deliver on the promise of its grand visions.

Raffaello Pantucci is director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute in London.