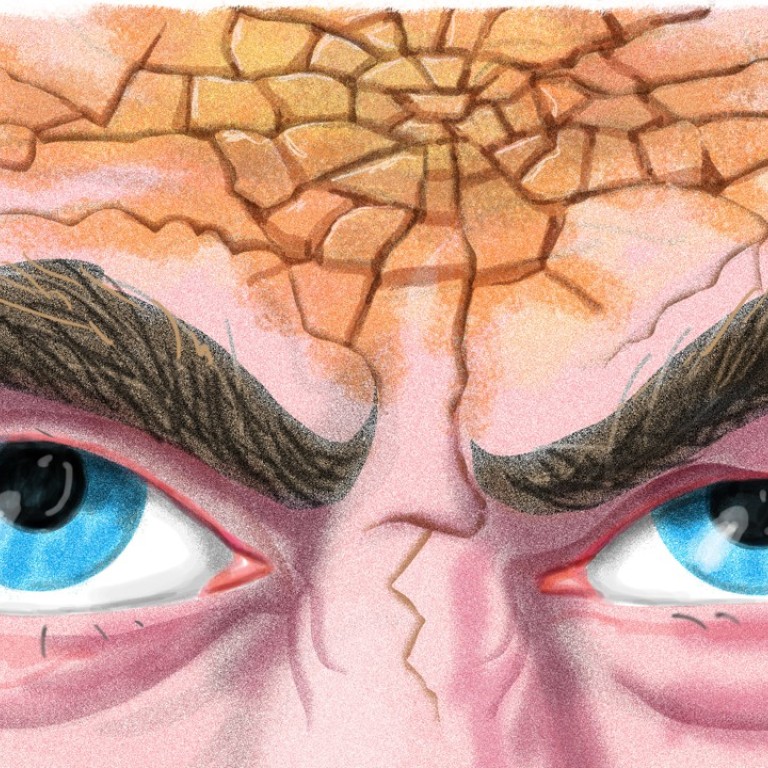

Charlottesville hotheads are a reminder that global warming threatens us all with summers of discontent

Andrew Sheng says extreme weather, migration and violence triggered by climate change are threatening governments and beginning to lay waste to the Earth, and cool heads must prevail to prevent further disaster

What happened in Charlottesville, US, showed that temperatures and tempers are flaring in this long, hot summer. Is the Arab spring spreading worldwide due to global warming?

From February to August 2010, a large-scale drought and famine occurred in Africa’s Sahel region, the belt south of the Sahara Desert stretching from Senegal, Northern Nigeria and Mali to Sudan. The drought killed an estimated 260,000 people and caused migration northwards to North Africa.

Indeed, before the fall of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in late 2011, the EU paid Libya €50 million (HK$459 million) in October 2010 to stop African migrants passing into Europe. From 2006 to 2011, Syria suffered drought and famine over 60 per cent of its land area, causing massive crop failure and loss of herds.

Trillion-tonne iceberg, 70 times the size of Hong Kong Island, breaks off Antarctic shelf

Increasing scientific evidence shows this continual rise in temperature will lead to more cyclones, rises in sea levels, a faster decline in the polar ice caps and more unpredictable weather changes.

Failing governments don’t have the capacity to address the challenges ... particularly in the Middle East and North Africa

The US National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends report in January argued that global tensions will rise in the coming five years from five key stresses: economic, political, social, geopolitical and environmental. The economic stress comes from slowing global growth, creating less resources to deal with the huge welfare and social gaps that shape politics. Political stress is rising because failing governments don’t have the capacity to address the challenges they face. This is particularly evident in the Middle East and North Africa, the most water-stressed region in the world.

The report argues that “societal confrontation and polarisation – often rooted in religion, traditional culture, or opposition to homogenising globalisation – will become more prominent in a world of ever-improving communications”. Improved communications have not only enabled militant extremists and terrorist groups to have a transnational presence, but also infectious diseases to spread faster.

Watch: Arab spring revisited – Egypt

Geopolitical stress has arisen because of growing inter-state rivalry for power and resources.

Finally, environmental stress is moving centre-stage as global warming generates more freakish storms, melts ice and makes sea levels rise. This worsens the coping abilities of fragile governments, already weakened by corruption, social dissent and insufficient resources.

These five stresses are mutually reinforcing, as deterioration in one makes the others worse. For example, if the sea level rises, not only would food-producing zones, such as the Mekong Delta, be subjected to flooding, the increased salt content would also reduce rice production. It has already been claimed that greater ocean weight stresses on continental shelves may lead to more earthquakes and volcanic disruptions.

The costs of dealing with natural disasters are becoming serious

Watch: Protests as Donald Trump withdraws US from Paris climate accord

Another study by psychologists Courtney Plante and Craig A. Anderson this yearsuggested a high correlation between heat stress, and aggression and violence. Children growing up in climate-stressed countries may become more antisocial, from undernourishment due to food and water shortages. The other impact is ecomigration-driven conflict. The illegal migration of over 15 million Bangladeshis into India, according to a Carnegie India 2016 study, created social tension along border areas.

Climate change is no longer a long-term issue, but a clear and present danger. Each of us has to take responsibility for it, because it is collective human excessive consumption that is changing our ecosystem. A hotter and more violent Earth is not fake news.

That is why “Earth First” comes before “America First” or “individuals first”.

Hotter climates will need cooler heads than Trump’s to think through what we should be doing to deal with climate change.

Andrew Sheng writes on global issues from an Asian perspective