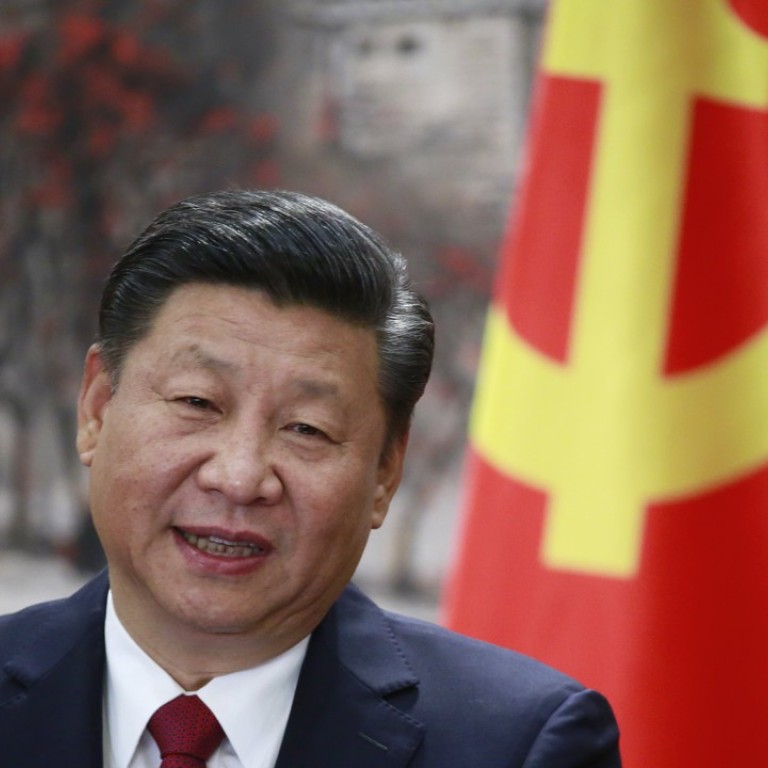

Westerners extolling all-powerful Xi Jinping are missing three important points

Niall Ferguson says America’s decline has left Western observers awed by Xi Jinping’s authority, even though they have no idea yet how effectively, or ruthlessly, he may use that power

A new era dawns for Xi Jinping’s China, but what will it mean for the rest of the world?

To The Economist, Xi is now “the world’s most powerful man”. Xi offers a “long-term view of China’s ambition”, declared The Financial Times last week. “This president has an iron grip on power and a strategy to reach global pre-eminence.”

Fareed Zakaria, of CNN, wrote almost rhapsodically about the implications of the 19th party congress, which ended last week: “This party congress made clear that [Xi] is no ordinary leader. For the rest of his life, Xi and his ideas will dominate the Communist Party of China.”

Trump to lobby China on North Korea and trade during Beijing summit with Xi Jinping

To the author of The Post-American World, the implications are clear. “These changes are ... occurring against the backdrop of the total collapse of political and moral authority of the United States in the world. China [has] signalled that it now sees itself as the world’s other superpower, positioning itself as the alternative, if not rival, to the United States.”

This point was seemingly lost on Trump, who tweeted that he had called Xi “to congratulate him on his extraordinary elevation”.

We’re supposed to be impressed that, to quote The Economist, Xi’s “grip on China is tighter than any leader’s since Mao”? Mao was responsible for the deaths of millions in the 1949 revolution, the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. If Mao is Xi’s model, China is more likely to become a vast North Korea than a post-American colossus.

Opinion: Why China’s Xi might come to regret all that power

But what is Xi’s thought? The relevant amendment to the constitution runs to nearly 3,000 words, but in essence it combines the familiar (“socialism with Chinese characteristics”) with new themes introduced by Xi: “the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation”, “green development”, anti-corruption and the party’s primacy over the military.

‘Xi Jinping Thought’ enshrined in the party charter

Why Xi Jinping’s China model is about both material and spiritual rejuvenation

Not much here is Maoist: “We shall give play to the decisive role of market forces in resource allocation ... advance extensive, multilevel and institutionalised development of consultative democracy ... [and] enhance our country’s cultural soft power.”

What a new era with Xi Jinping’s ‘dream team’ means for Hong Kong

If the Chinese are lucky, Xi will turn out to be an enlightened absolutist, like Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew. If they are unlucky, he will be another emperor who fondly dreamt of controlling a fifth of humanity. Worst case – but least likely – he’s Mao 2.0.

Why China is reviving Mao’s grandiose title for Xi Jinping

Maybe modern information technology can give totalitarianism a new lease of life, as big Chinese tech companies make available the personal data of all Chinese netizens. Maybe, thanks to big data, economic planning can work where previously it failed. I wouldn’t bet on it. To judge by the amount of foreign investment wealthy Chinese are making in spite of tightened capital controls, neither would they.

Niall Ferguson’s new book is The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power