Advertisement

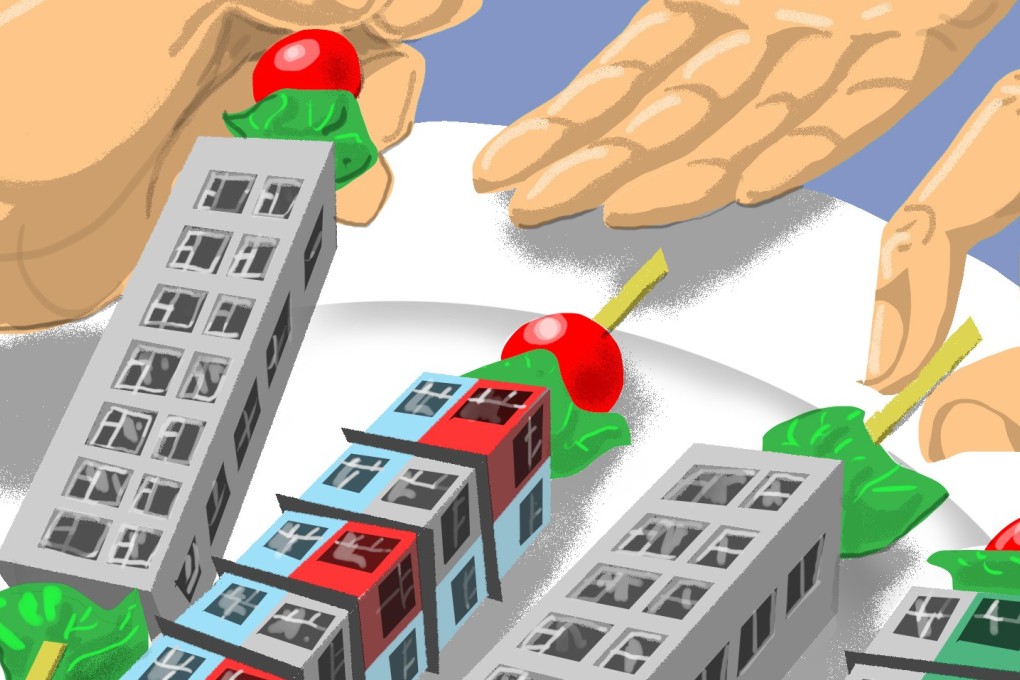

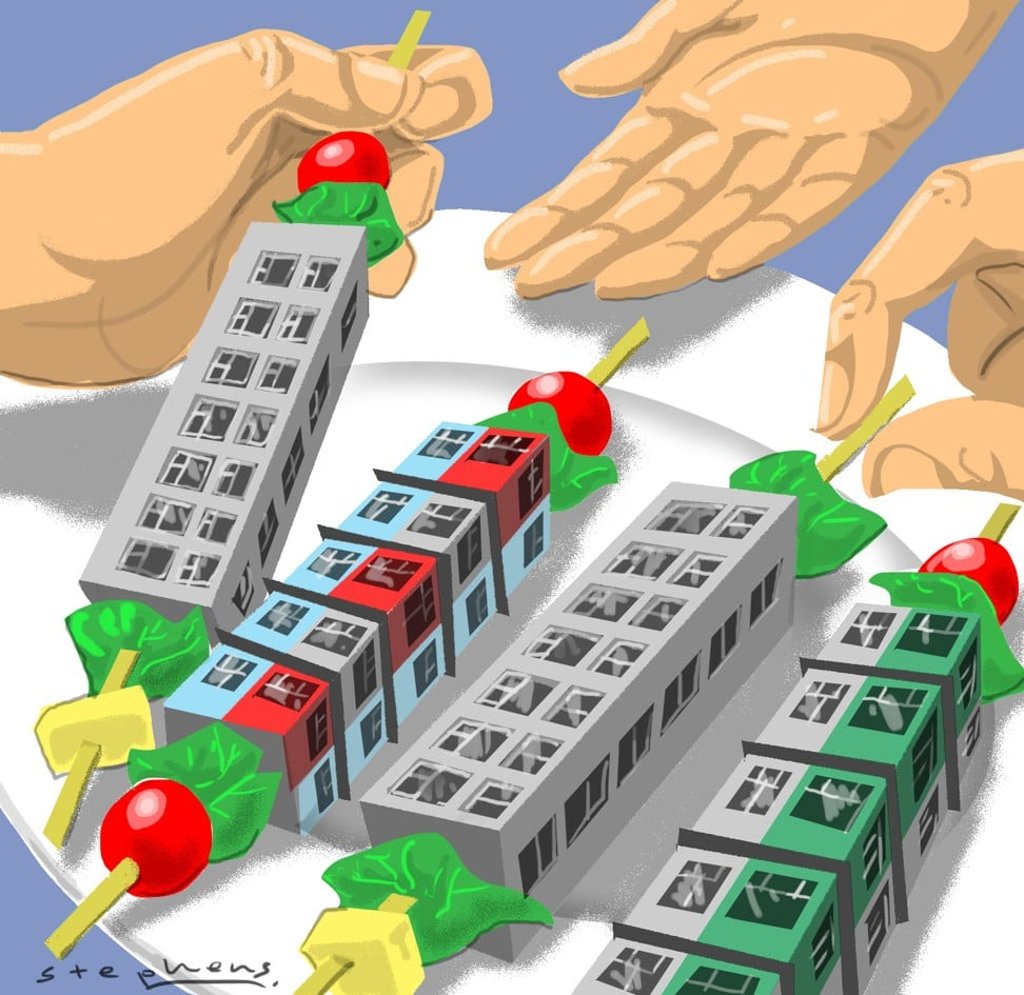

Hong Kong’s public housing should cater to the masses, as Singapore’s does

Wilson Wong says instead of tinkering with stop-gap measures to ease the shortage of good quality, affordable housing, the government must redefine the nature and purpose of its public programme

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

While not matching Hong Kong in fervour, land-scarce Singapore, too, has its share of housing angst. Both cities try various ways to optimise land use. What distinguishes the Lion City from the Fragrant Harbour is the former’s considerable success in housing the bulk of its population in relatively affordable, high-quality public housing.

In 2016, about 30 per cent of Hong Kong people lived in government-subsidised rental flats while another 16 per cent lived in flats they bought at a subsidised price. The newer flats, both for rent and sale, are actually of relatively high quality, comparable and in some cases superior to those offered by the private sector.

Advertisement

Many Hong Kong residents live in shabby private housing, which includes subdivided apartments in economically depressed areas such as Sham Shui Po. Government statistics reveal that, in 2015, some 200,000 people were living in 88,000 subdivided flats across Hong Kong.

The key advantage of public housing is obviously cost, with monthly rentals going for around HK$2,000 (for a flat for two to three people), while maintenance and management charges are waived. In a city with the dubious distinction of being the world’s priciest housing market for seven years running, this cost advantage is attractive.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x