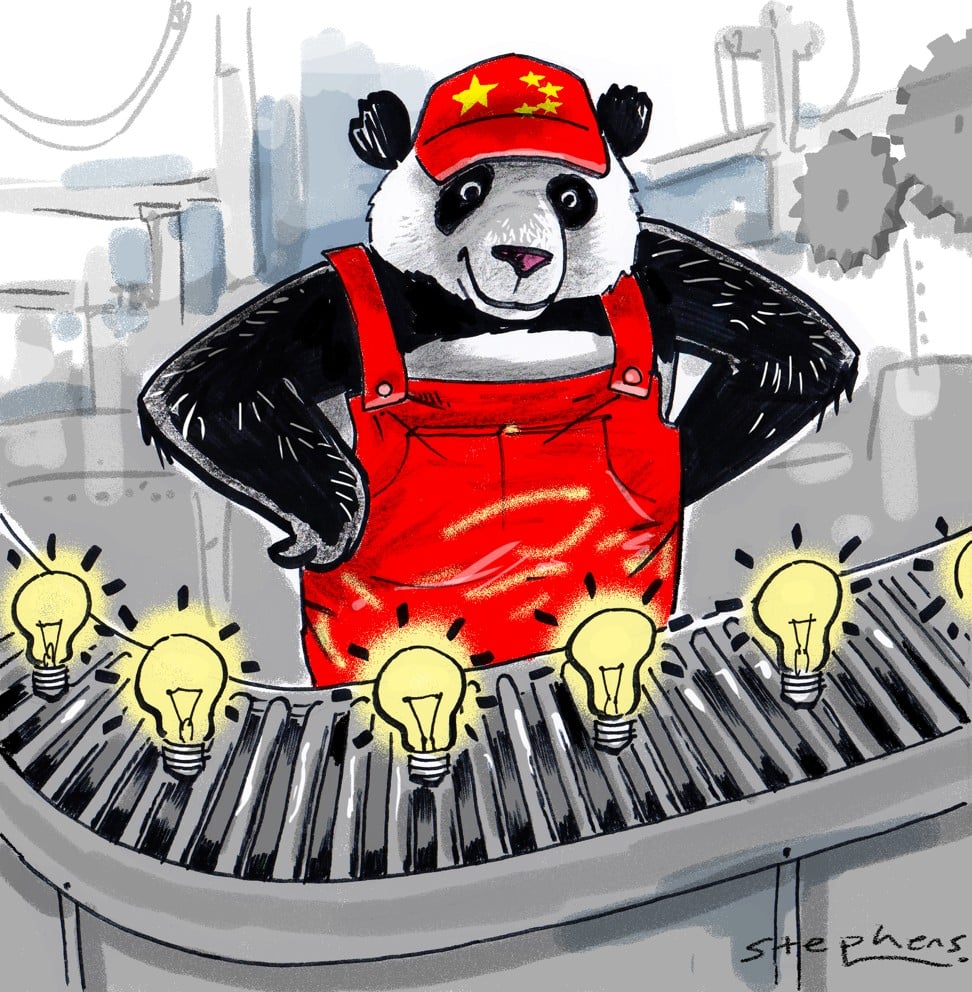

China must innovate now or lose its economic competitiveness

Xu Qing says profound changes in demography, the environment and market conditions are forcing a transformation on the country, but China has the capacity to shift gear, and upgrade its economy to one driven by innovation

Now, the low-hanging fruits have been picked and the old economic engines are spluttering.

First, the demographic dividend is diminishing and society is rapidly ageing. The number of working-age Chinese has been dropping, and the times of a seemingly unlimited supply of young and cheap labour are gone. Meanwhile, the elderly population is set to skyrocket as a result of the low fertility rate and increasing life expectancy. Such demographic pressures signal an urgent need for productivity gains through technological innovation and upgrading.

Second, the high level of credit supply has left China with diminishing returns on capital and a high debt-to-GDP ratio. Regulators have made deleveraging a top priority. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that the liquidity floodgates will be opened again to stimulate growth, and in the remote possibility that credit growth speeds up again, its effectiveness will be much less profound.

Third, China’s competitiveness in low-value-added exports is declining, with rising labour costs and regulatory costs, such as for environmental protection, driving up corporate expenses.

On top of that, China’s large trade surplus and “unfair trade practices” are often criticised by developed countries. As a result, economically and politically, it is hard for China to expect exports to drive growth.

China scours the globe for talent to transform into world leader in artificial intelligence and big data

Fortunately, China has the ability to scale the mountain of innovation. It has the human capital to propel research and development. Even though the generic labour force has been shrinking, there has been a surge in graduates in the natural sciences and engineering. This follows higher-education reform in 1999 when university admission was expanded.

Watch: Attracting the young into the tech sector

China is making a point to woo overseas talent. It has offered attractive financial rewards, career paths, research facilities and funding under various schemes, such as the central government’s Thousand Talents Plan.

Why money and prestige aren’t enough to lure foreign scientists to China

Watch: Chinese internet companies spend billions on research and development

China’s hi-tech economy is taking shape, thanks to its entrepreneurs and innovators

Government fiscal policies are supportive of R&D. In China, 150 per cent of R&D expenditure can be tax deductible, and the preferential corporate tax rate is cut to 15 per cent from the prevailing 25 per cent for hi-tech enterprises. Also, governments at different levels directly grant subsidies to select research projects.

China’s disadvantages have often turned out to be blessings in disguise

China’s disadvantages have often turned out to be blessings in disguise. For instance, the inefficient services and logistics infrastructure stimulated the growth of e-commerce, while the low credit card penetration led to the wild success of Alipay and WeChat Wallet. The same logic probably holds for alternative-fuel vehicles too. Underserved Chinese consumers are less demanding than in other countries, and are more willing to embrace new products and business models.

How China’s can-do generation will be the engine of growth, both at home and globally

Watch: How AI made phone cameras more fun

With all the efforts in R&D and innovation, China has been catching up in both the quantity and quality of production of scientific knowledge. Its global share of scientific papers has been growing at a far higher rate than developed countries’, and it has been awarded the largest number of patents since 2015.

In the industrial sphere, value-added created by hi-tech manufacturing has been climbing rapidly and approaching the US level. In areas like telecoms equipment, high-speed railway, and alternative-fuel vehicles, China is already in the leading league in the world.

Watch: Travel 658km in just three hours on China’s latest high-speed rail line

There are still many challenges. China still lacks fundamental research, which is critical but takes time to produce tangible results. China’s research and development workforce was only 0.19 per cent of total employment in 2013, far behind Japan (1.02 per cent) and the US (0.87 per cent). In addition, the institutional structure of universities and research institutes is not yet ideal for top-notch research work.

However, the imperative to innovate and upgrade has never been stronger and the advancement never more pronounced. China is in the early phase of a transition from low-value-added to high-value-added. Investors who ignore such developments do so at their own risk.

Xu Qing is a senior investment manager at Neo-Criterion Capital Limited, an investment company specialising in pan-China equities