Any US push for maritime interceptions to counter North Korea will go nowhere

Mark J. Valencia says the US failure to win UN Security Council authorisation for the use of force to interdict ships stems from a lack of trust in its intentions. The council’s other members are likely to oppose any such measure in the wake of Pyongyang’s latest missile tests

But any such action without Security Council authorisation would have to overcome many legal and political concerns.

Such a radical approach has the support of prominent US commentators like Frank Jannuzi, president of the Mansfield Foundation. He argues that a “stop-and-frisk policy” towards North Korean ships might make sense and would be “far preferable to launching an unnecessary and extraordinarily dangerous war”. This rationale may appeal to many others.

Watch: North Korea’s latest missile launch on November 28

What’s next after North Korea’s successful launch of rocket that can strike US?

However, most troubling to many countries, a Security Council resolution authorising the use of force to interdict shipping on the high seas would change a centuries-old fundamental principle of international law – freedom of navigation. Indeed, it would essentially legalise, in the case of North Korea, what would otherwise be an act of war. It would also set a dangerous precedent by eroding a right that ironically has long been insisted upon by the maritime powers, especially the US.

This is not the first time the US has tried to do this. Because of these previous attempts – which failed – we know some of the political obstacles that the US would have to overcome to get Security Council approval for a resolution authorising interdiction of shipping on the high seas with the use of force.

First of all, it would have to win the support of the full council.

North Korean coal piles up as sanctions take their toll

This was a pretty robust resolution. However, banned items can still be “smuggled” in and out of the country. That is why authorisation of interdiction is so important to the US strategy.

How North Korea evades UN sanctions

China and Russia opposed the use of force because they did not want to encourage and allow US military operations in waters under their jurisdiction. They were probably also concerned that the precedent might one day be used by the US against other “rogue” states. Moreover, they believed that forceful interdiction would draw a violent response from North Korea and that the interpretation of “reasonable grounds” to intercept would be heavily influenced by the US. More pragmatically, they believed that interdiction would not be fully effective and that realistic negotiations are the way to resolve this problem. They probably still have such concerns.

Some say that such interdiction would be the Proliferation Security Initiative “on steroids”.

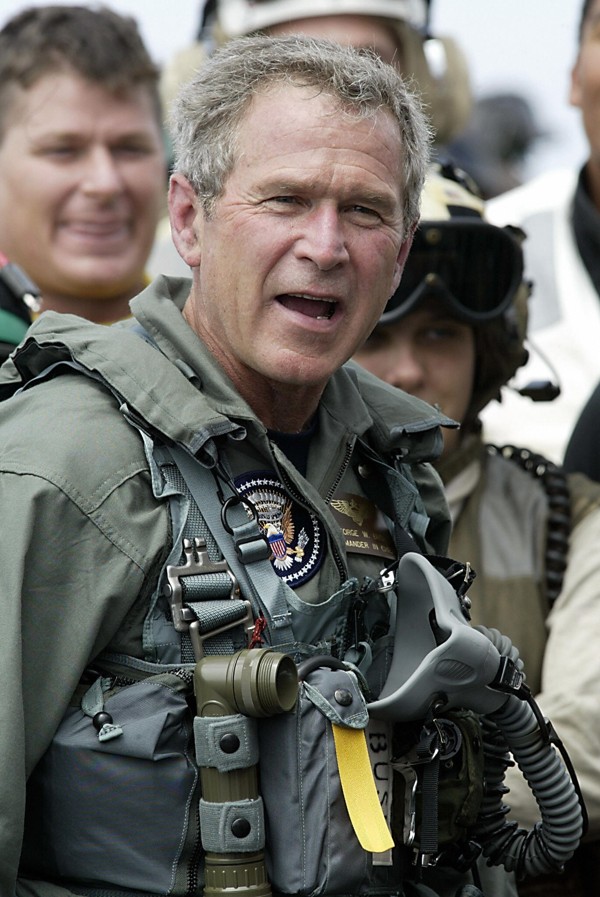

The initiative was launched in 2003 by then US president George W. Bush to prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction. The focus was to be on interdiction, which was seen as a way to fill the gaps in the existing non-proliferation architecture. The original concept was for an ad hoc “coalition of the willing” to intercept vessels carrying weapons of mass destruction and related materials moving to and from North Korea. Such actions were to be outside the UN system and thus not constrained by a cumbersome decision-making process and second-guessing.

Initially, the US argued that participants could and should undertake interceptions based on actionable intelligence – what it called “reasonable cause”. But the fact that the US has not ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which prohibits such unilateral interdictions, raised suspicions that the US wanted to operate outside international law. Moreover, the secrecy surrounding initial interdictions under the initiative has raised suspicions that the US is employing politically motivated double standards and extra-legal methods.

The good, bad and downright ugly aspects of US naval operations in the South China Sea

The problem for the US in pushing for interdiction with the use of force is a lack of trust. In some countries’ eyes, the US has a history – even a pattern – of intelligence failures, double standards and duplicity dictated by its narrow national interests. To have even a chance of China and Russia’s assent to interdictions on the high seas using force, the US would have to yield real control of the decision to intercept, the definition of “reasonable grounds” to do so, and the actual interdictions themselves. But it is doubtful that Washington would be willing to give up such control.

Given these considerations, the Security Council is unlikely to approve of interdictions as envisioned by the US. A frustrated America may go it alone; if it does, it would have to face legal and political implications reaching far beyond the issue at hand.

Mark J. Valencia is an adjunct senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China