How Trump’s America helped China and South Korea become friends again

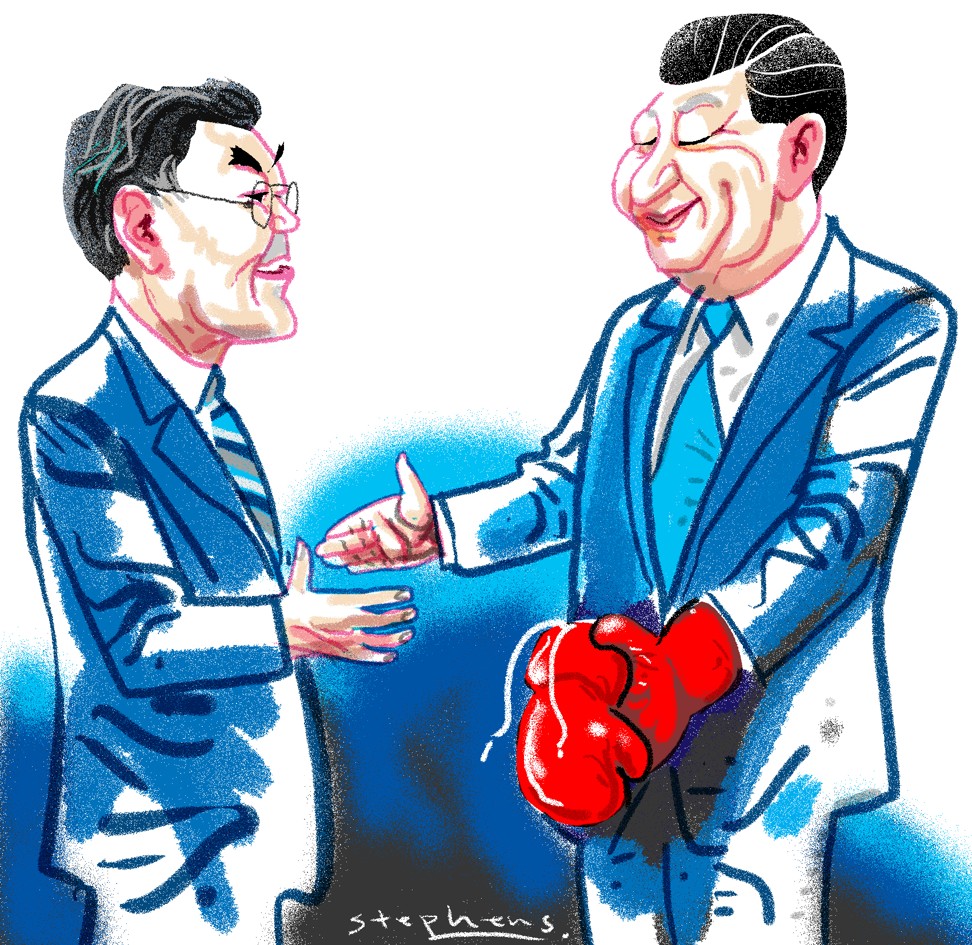

Zhang Baohui says the rapprochement between Beijing and Seoul, after relations were damaged over THAAD, has much to do with a more moderate Chinese foreign policy, inspired in no small part by the erosion of American soft power under an isolationist Donald Trump

In return, Beijing agreed to fully restore bilateral ties by ending hidden sanctions and by inviting Moon to visit China this week.

Multiple factors have contributed to the rapprochement. The most important one concerns China’s shift towards a softer foreign policy.

Moon Jae-in hopes to rebuild trust during visit to China

Why South Korea’s promises on THAAD and a US-Japan alliance are so important to China

South Korean President Moon Jae-in seeks to reconcile with Beijing after tensions flared over THAAD

However, apart from a moderate foreign policy, there could be two other explanations behind the Beijing-Seoul rapprochement.

The first focuses on the role of individual leaders. The standard assumption in analysing foreign policies is that leaders are cool-minded people who base their decisions on rational evaluations of national interests. This is far from true. In reality, decision-makers are also human and thus liable to being influenced by emotions.

America deploys Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) system 250km south of Seoul

Park Geun-hye watches Chinese military parade marking V-Day in Beijing

Xi Jinping in military parade speech vows China will ‘never seek hegemony, expansion’

In that context, Park’s decision to deploy THAAD last year was a major blow to the Chinese, who felt betrayed. Xi may well have shared the feeling. It was reported that when Park tried to call Xi to explain the South Korean decision, he refused to answer the phone.

Xi’s emotions could have profoundly affected China’s response to THAAD. He had invested heavily in a special relationship with Seoul, only to be “betrayed”. Indeed, Korea was the only middle power to have received major power status in China’s foreign policy.

Will Xi Jinping’s charm offensive win over China’s wary neighbours?

The second explanation relates to China signalling its resolve to punish countries that harm its core interests. That may have been the design behind Beijing’s economic retaliation, both direct and hidden, after Seoul’s deployment of THAAD. In addition to making an attempt to have Seoul reverse its decision, Beijing was using South Korea as an example, to signal to the region that other countries cannot hope to get away with harming core Chinese interests.

In that context, South Korea became the “chicken” that had to be killed to warn the “monkeys”. The seeming Chinese intransigence on the matter was designed precisely to enhance China’s reputation that it will do what it says. Essentially, China wanted to use the case to enhance its credible deterrence against other countries that may also harm its core interests.

This image of a rather ‘stubborn’ China sent the desired signals to both South Korea and other countries

That China has agreed to restore the relationship with Seoul could reflect its calculation that these objectives had already been achieved. Indeed, China was seen as rather persistent and headstrong in its “punishment” of South Korea.

This image of a rather “stubborn” China successfully sent the desired signals to both South Korea and other countries – that China means what it says. It can now start to improve the damaged relationship with Seoul before strategic costs begin to exceed benefits.

However, the most important cause of the reconciliation concerns the reorientation of Chinese foreign policy. This year, the world has seen a confident China pursue and exercise international leadership. This attempt has been induced by the strategic opportunity presented by the Trump administration, which has damaged US global leadership and soft power.

According to the realist theory of international relations, great powers are typically offensive in that they utilise any opportunity to gain an advantage over strategic competitors. Trump’s neo-isolationist and unilateralist inclinations have given China a golden opportunity to enhance its prestige, status, and international leadership.

‘The Chinese have figured out how to play Trump’: try flattery

In this context, China has assumed a more moderate foreign policy stance. Beijing now emphasises the use of soft power to enhance its international standing, while downplaying the importance of traditional security issues.

To be seen and accepted as a legitimate leader in world affairs, China needs to project benign signals in both regional and global contexts. The relationship with Seoul has benefited from this development, resulting in the Chinese decision to restore bilateral ties.

Trump isolated on climate and trade at G20 summit in Hamburg

Why the US is no match for China in Asia, and Trump should have stayed home

Zhang Baohui is a professor of political science and director of the Centre for Asian Pacific Studies at Lingnan University in Hong Kong. He is the author of China’s Assertive Nuclear Posture: State Security in an Anarchic International Order