#MeToo and Vera Lui show why Hong Kong needs better sex education classes

Paul Stapleton says it is time Hong Kong emerged from the extreme conservatism over sex education in schools, and in society as a whole, which makes even celebrities like Vera Lui wait years before being able to talk about sexual assault

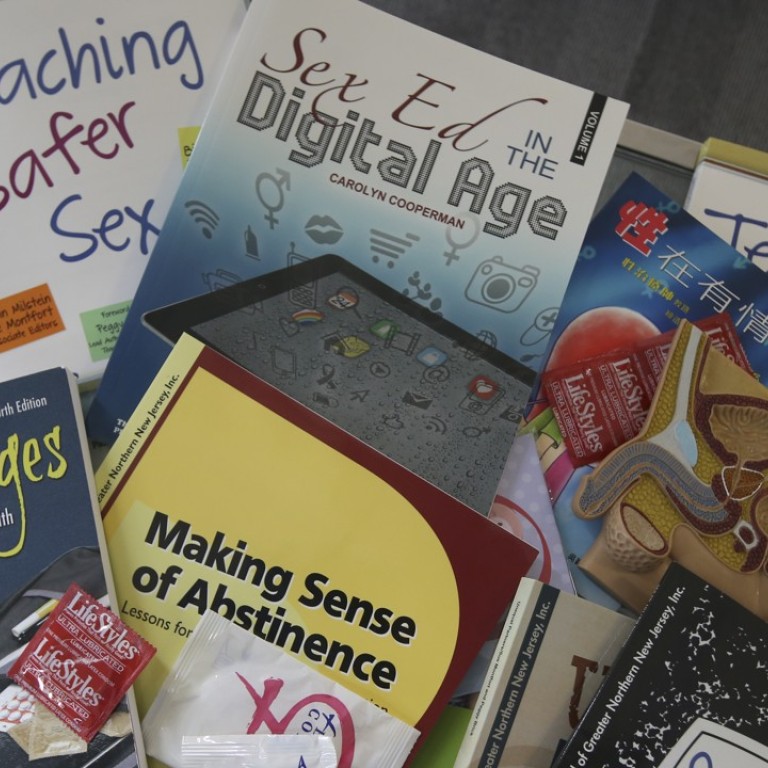

At present, the curriculum includes a mandatory subject called moral, civic and national education, in which sex education is buried among other topics, such as human rights, anti-drug education and sustainable development. Biology classes include explanations of human reproduction, but this mostly concerns microscopic mechanisms within the body.

Simply put, the reality is that, among local schools, sex education is not mandatory and lacks systematic implementation, with a few teachers providing detailed instruction, while many more gloss over it.

#MeToo movement unearths heartbreaking reality of sexual assault in Hong Kong

As a contrast to this, I recall my own experience as a student in sex education classes over a generation ago, in 1970s Canada.

At that time, we attended a class called “health,” in which various topics related to physical health, including sex, were discussed.

I specifically recall a couple of episodes all this time later. In one class, I remember one student asking the young female teacher what an orgasm felt like, and receiving a candid answer. On another occasion, a male teacher taught how to use a condom.

Hong Kong’s sex education crisis: why people turn to sex workers for knowledge

Sure, there were plenty of sniggers from the boys along with some blushing among the girls, but the fact that I can remember these episodes after so many decades speaks of both their importance as well as their intrinsic interest. It also underscores the potential power of formal education. These two lasting memories are derived from teaching episodes that emerged from an enlightened curriculum.

Hong Kong does not want to talk about sex, but Janus Tiu does

Talks on sexual abuse in sports lined up after Vera Lui revelation

Along with explanations of the intimate details described here, we also learned about the physical processes of reproduction, as well as the repercussions of sexual intercourse and pregnancy. And while the 1970s in North America are not well known for sexual restraint or low abortion rates, one can imagine, without the type of sex education I received, how much worse it might have been.

And this brings us back to our present curriculum here in Hong Kong. Without a doubt, any change in how sex education is taught has to be approached carefully, perhaps with expert instructors sent out to hold special classes, as sometimes happens now in a few enlightened local schools.

Let’s talk about sexuality, Hong Kong: young people need to know about sex and relationships

The #MeToo movement presents an opportunity to not only bring the topic of sexual harassment into the open, but also reassess how we educate our children with regard to human reproduction and all of the behaviour that surrounds it.

Paul Stapleton comments on local educational and environmental issues