Just Saying | K-pop is an infectious disease, not a cultural export to be proud of

Yonden Lhatoo highlights the tragic suicide of boy band idol Jonghyun to argue that the so-called Korean Wave of cultural entertainment is an affliction that the world would be better off without

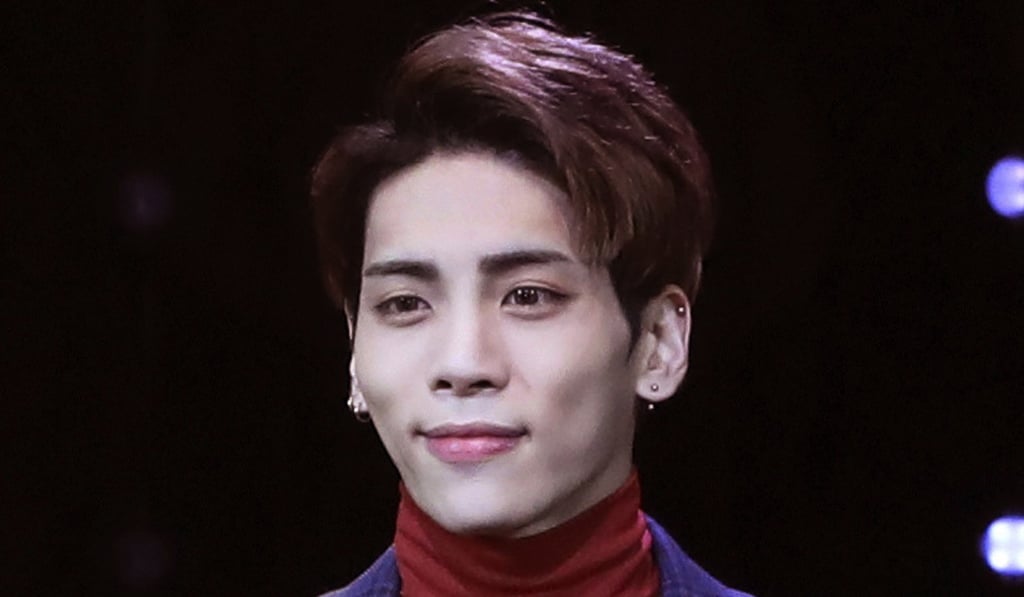

To be honest, I had never heard of Kim Jong-hyun until the recent media coverage of his suicide snapped me out of blissful ignorance.

Blame my cluelessness on the fact that, to the untrained eye, all of South Korea’s prettiest and shiniest humanoid cultural exports look and sound exactly the same. I can’t tell them apart.

Hong Kong fans flood Twitter in outpouring of grief over death of SHINee lead singer Jonghyun

The circumstances of the 27-year-old pop idol’s tragic death have put the spotlight on the sheer pressures and shameful exploitation that young people like him in the entertainment industry have to face.

“I am broken from inside. The depression that gnawed on me slowly has finally engulfed me entirely,” the harrowing suicide note he left behind read.

“I was so alone.”

You know what’s even sadder than the plaintive cry of this young man cut down in his prime? The fact that it will do nothing to end the true horrors of Hallyu, in essence a pandemic of trashy, shallow entertainment masquerading as culture that has inexplicably captured hearts and minds across the globe.