China has changed, and so should Hong Kong lawyers’ understanding of ‘one country, two systems’

Tian Feilong says there is a grievous mismatch between the reality of a rising China and growing cross-border integration, and Hong Kong legal elites’ arrogant belief that the common law system is superior to the nation’s legal system, and therefore immune to change

Clearly, some in Hong Kong are unaccustomed – even averse – to this new development of “one country, two systems”.

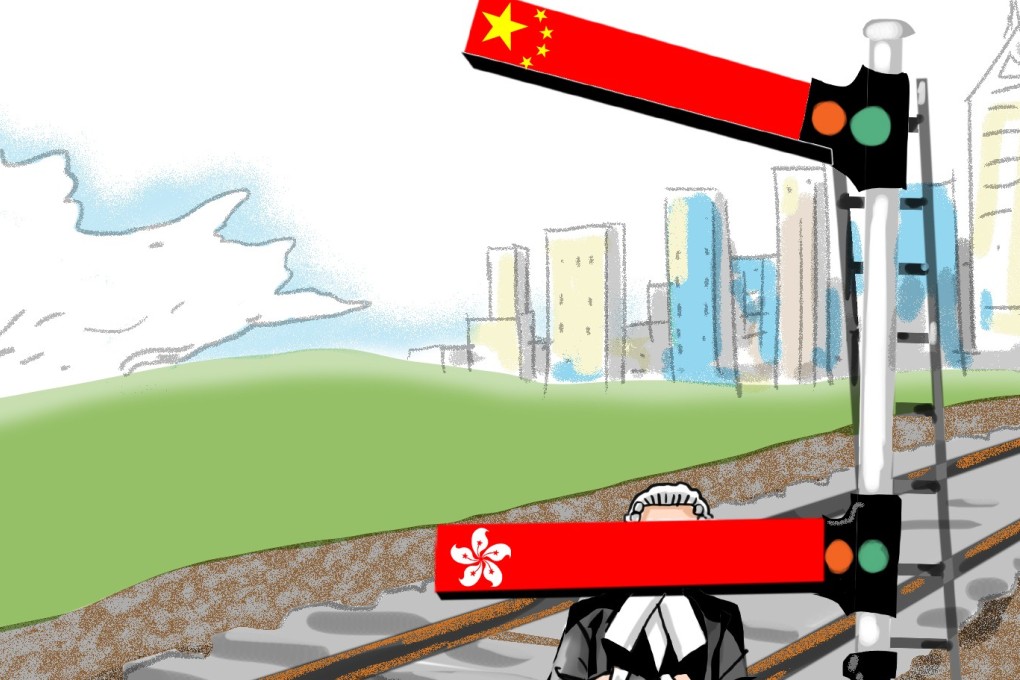

The quarrel over the legality of the decision pits the political elites in Beijing against the legal elites in Hong Kong. At its heart, the dispute comes down to a clash between the autonomy of the common law system in Hong Kong on the one hand, and the sovereignty of the central government on the other.

Beijing has ultimate control of Hong Kong – that’s the reality of ‘one country, two systems’

The co-location arrangement will not only benefit Hong Kong’s economy, but also facilitate the political integration of Hong Kong and the mainland. Constitutionally, it shows great respect for both Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy and public opinion. Yet it has failed to win the trust and acceptance of the leading lights of the city’s opposition camp.