Not a zero-sum game: global governance must adapt to the new US-China equation

Daniel Russel says new models of global governance that promote healthy competition as well as cooperation on big challenges are needed to address the changing dynamics between the US and China, and that the latter’s new regional initiatives could be a road test of the country’s emergence as a world leader

Hong Kong is an ideal place to examine the issues of China, the US and global governance. Few places have benefited more than Hong Kong has from two of the major developments of our era: China’s emergence as an economic powerhouse and the globalisation of the world economy.

One of the reasons that Hong Kong has been effective in facilitating China’s integration into the international economy is its long-standing status as an international financial centre. That status is based on its openness to commerce and foreign investment, its independent and professional legal system, its robust and transparent regulatory regimes – and, of course, its open press environment and high-quality publications.

So not only has Hong Kong done well for itself, but its transparency, openness and adherence to international norms have also helped China navigate, and thrive, in the present-day international system.

How ‘one country, two systems’ is tearing Beijing and Hong Kong further apart

But the broader point is that since the launch of economic reforms in 1978, China, and by extension Hong Kong, have benefited immensely from the existing international system. Over time, China has become both a member, and a key beneficiary, of most international regimes. And it’s no accident that China’s economic boom accelerated following its accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001.

But China is changing, and changing quickly. The world and its international institutions and regimes have sometimes been slow to adjust. China has sometimes been seen as reluctant to “pay its dues”.

There’s a lot for China to be proud of. But the expectations – and the challenges – are immense

There’s a lot for China to be proud of. But the expectations – and the challenges – are immense.

As the economic complementarity of previous decades gradually dissipates, greater stress is placed on both the bilateral relationship and the global system. What that means is that upgrading global governance models to meet these new dynamics has assumed added importance.

Global governance at a crossroads

One criticism of the current global governance system is that it has generally been slow to adjust, and slow to grant China a voice commensurate with its growing stature. As much as China has benefited from the global governance rules and institutions, Henry Kissinger pointed out that China is adjusting to an international system that was developed in its absence, on the basis of a programme it didn’t participate in developing.

So reform is needed, and needed for a number of reasons. The international system is under stress, not only due to China’s rise, but also from globalisation, automation, artificial intelligence and information technology, from changes so seismic we have only begun to grasp their impact. As a result of these changes, it is very much my view that global governance is approaching a crossroads.

For one thing, shifting attitudes in both the United States and China have contributed to dissatisfaction with the current nature of the global governance system. But the sources of US and Chinese discontent are different.

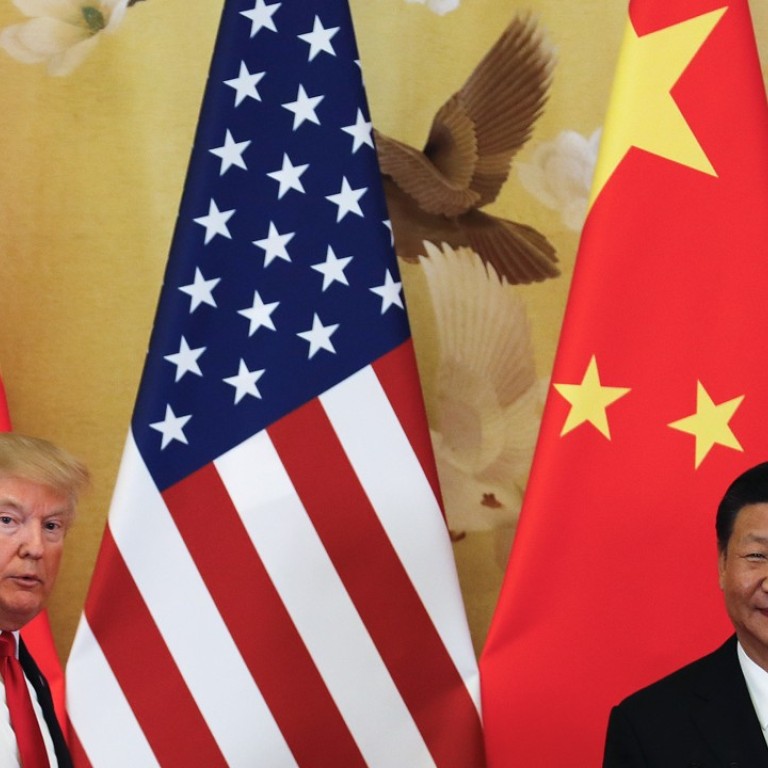

America first is America alone: US President Donald Trump becomes an increasingly isolated figure on world stage

Will Donald Trump make China great again?

How South China Sea ruling can be a ‘win-win’ for China and the world

These negative perceptions – the suspicion that global norms and institutions are being unfairly used to undermine Beijing’s interests – are exacerbated because China is a latecomer to global engagement and is excluded from some institutions and is under-represented in others.

The US, meanwhile, has been suspicious of what it sees as efforts by China to undermine global institutions, to “freeride” or exploit loopholes and protections, and to exempt itself from rules and norms.

The recent national security strategy bluntly declares that China seeks to displace the United States in Asia and reorder the region in its favour. It argues that past support for China’s rise, and for hopes for its integration into the post-war international order, were mistaken. That China is contesting America’s geopolitical advantages and trying to manipulate the international order.

Strong stuff.

Finding a common interest

So where does that leave us?

Even Graham Allison says that avoiding the Thucydides Trap requires leaders to make good decisions. Exercising good judgment will be ever more critical if the US charts a more self-interested, some might say nationalist, foreign policy, at the same time that China increases its global engagement.

We face the risk of a shift towards a more zero-sum, ‘blood and soil’, cutthroat world – a world we don’t want to live in

To deal with these challenges and risks, both China and the US must find a way to surmount their mutual suspicions.

Specifically, they need to identify a common interest in building a global governance system that accommodates China’s legitimate interests, but also preserves the foundations of a rules-based international order that is respectful of universal rights and freedoms. Doing so is essential, because the alternative is so dangerous. We face the risk of a shift towards a more zero-sum, “blood and soil”, cutthroat world – a world we don’t want to live in.

Professor Joe Nye of Harvard made the point that the risk we should focus on isn’t really the Thucydides Trap. It’s the risk that the US might curtail its global leadership and participation in international institutions, while China approaches global engagement and international institutions largely as a means to satisfy so-called core interests and national goals.

America First and China vs Japan: Is Asia ready for the next financial crisis?

No country should be expected to ignore or abandon its own interests. But the world can’t afford for major powers to neglect their global responsibilities.

That means that now is the time for both the US and China to check their worst impulses when it comes to global governance. Because if the US were to back away from multilateral diplomacy and organisations, and if China were to engage selectively with an eye to tactical advantage and protecting “core interests”, we would find ourselves in a more unstable world.

The key here is that the US should not walk away from its global leadership responsibilities, and China should seek to ensure that its multilateral efforts complement, not undermine, existing global governance institutions.

It is clear that avoiding a zero-sum world is a project that will take concerted efforts in both Washington and Beijing.

Can China be trusted to do the right thing?

I’m the first to admit that there is a lot that the Trump administration will need to do to show that “America first” does not lead to “America alone” and that Washington is up to the challenges that automation and the knowledge economy pose to US prosperity and global leadership. There is plenty that the US should do. But since I am in Hong Kong, let me focus on China.

To meet the high expectations set forth by Xi, China will have to make a sustained effort to win the trust and confidence of its international partners.

Is China willing to take on significant responsibility for providing global goods and shouldering international burdens?

I have no doubt that China has the material capacity to achieve Xi’s ambitious agenda, but some big questions are outstanding: Is China willing to take on significant responsibility for providing global goods and shouldering international burdens, often well beyond the specific needs of China as a nation? Is Beijing willing to show restraint, accept limits, and abide by international standards, even at the expense of some short-term advantage to China?

And, while I’m on sensitive ground here, let me raise a point that many of China’s friends in the West find particularly troubling: what will be the impact on prospects for regional or global leadership of Beijing’s use of technology and big data for repressive political and social control at home?

I ask these questions with humility because the answers are going to matter. These are prerequisites for other countries’ acceptance of an expanded Chinese leadership role in global governance over the long term.

According to the most recent Pew Poll in Asia, the response throughout major countries in the region to the question “How much confidence do you have in the Chinese president to do the right thing regarding world affairs?” was worryingly low – I’m talking single digits in many cases.

It’s important to get those numbers up. And my own belief is that it’s the decisions and behaviour of the Chinese government and companies that can do that, rather than speeches and white papers and paid inserts in foreign newspapers.

A Rorschach test of international attitudes to China

At the China Conference, we had a good session on China’s highest-profile multilateral project – the Belt and Road Initiative. This initiative is a key indicator of whether China’s growing international engagement is primarily about satisfying its national interests, or whether Beijing seeks to create a more prosperous, interconnected and win-win Eurasia through multilateral cooperation.

Now, not all of the international scepticism about the Belt and Road Initiative may be justified. There are some significant cultural differences at play. In the US, initiatives are launched with blueprints and handouts and detailed specifics and frequently-asked questions. In China, initiatives are presented as broad strategic directives from the political leadership with policy specifics to be developed over time. So in many cases, the opacity of new Chinese initiatives is met with scepticism in the West, and their vagueness and lack of transparency means that people are free to let their suspicions run wild.

This makes the Belt and Road Initiative something of a “Rorschach test” of international attitudes towards China.

Is the Belt and Road Initiative about co-opting and coercing its neighbours? Or is it about promoting connectivity and commerce based on mutual interest and mutual benefit?

Is it neocolonialism? Part of a Chinese sphere of influence via state capitalism? A geostrategic play to establish military bases for a blue-water navy and political leverage through crushing debt?

Or is it a sensible – even generous – investment of China’s excess capital and capacity? A programme to build up both China’s underdeveloped western regions and create more dependable supply lines and smoother trade networks to bring its goods to market?

The ‘Belt and Road’ projects China doesn’t want anyone talking about

It makes sense for China to work to prove the positive case, and for the US and other international partners to help steer the Belt and Road Initiative in that direction. And to be successful, we have to remember that there is both a practical and a moral component to leadership.

The vision of the initiative – connectivity and integration – must be credible and embraced by other countries

Secondly, it means that the vision of the initiative – connectivity and integration – must be credible and embraced by other countries.

Just recently, I read a good editorial in the Post citing Belt and Road Initiative problems throughout South Asia and urging sensitivity and respect in approaching China’s neighbours.

Belt and road, or a Chinese dream for the return of tributary states? Sri Lanka offers a cautionary tale

Going beyond a geopolitical power play

There are important steps that China can take to avoid these pitfalls and prove that the Belt and Road Initiative is more than geopolitical power play.

These include establishing responsible financial, environmental and labour standards for projects under the initiative, and ensuring that projects are transparent and inclusive with open, competitive bidding. Clear criteria for project selection and the establishment of anti-corruption standards commensurate with the Communist Party’s own domestic policies would go a long way to enhancing the initiative’s credibility.

The Belt and Road Initiative is also an area where we could potentially see a marriage between China’s infrastructure development prowess and the United States’ strengths in services: risk management, financial services, information technology, and so on. China can also show that the programme is inclusive by ensuring that foreign companies, both manufacturers and service providers, are involved.

These new initiatives serve as laboratories where China can learn to work successfully with foreign partners

I’ve used the Belt and Road Initiative as an example of how China can take positive steps to deepen its global engagement through new initiatives. And these new initiatives serve as laboratories where China can learn to work successfully with foreign partners in an international environment.

But at the same time, it’s important to avoid undermining the existing regional and global institutions that have widespread international support.

Yes, our models and mechanisms for global governance should be updated to reflect changing international realities and new challenges of the 21st century, but not at the expense of the important first principles that drove the creation of these institutions in the first place.

How can we best preserve the peace in Asia?

The first is that such institutions should play a binding role, drawing states to greater convergence around shared interests.

Second, is that international institutions should seek to mitigate historical distrust and circumvent historical patterns, such as the Thucydides Trap, by fostering opportunities for strategic dialogue.

Third, is that institutions should work to facilitate better management of crises and disputes.

And finally, that these institutions should develop the capacity to set forward-looking agendas to deal with future challenges.

These recommendations are a good reminder that there are both preventive and progressive rationales for good global governance. The US and China can work together in multilateral institutions, and work to improve them, not only to prevent problems but also to make progress on shared global objectives.

But to do this, the US and China must manage the differences in perspective and the mutual suspicions that have hampered our ability to achieve consensus on global governance issues in the past.

New areas in need of global norms

Let me give you an example of a domain that is desperately in need of global norms: cyberspace. This is a void that urgently needs to be filled, but the US and China differ even on the definition of the problem, let alone the solution: Is the goal to protect cross-border information flow or to block it?

Is our goal a free and open internet or cyber sovereignty and data localisation? For the US, cybersecurity doesn’t include control of content. For China, controlling content is the whole point. It is no easy matter for the US and China to find common ground sufficient to forge international consensus on cyber norms.

Let me give you another example that doesn’t involve technology: maritime resources. Like climate change in 2016, US-China cooperation on ocean sustainability can form the nucleus of meaningful international cooperation. Overfishing, much of it illegal and unreported, has depleted fish stocks in the Pacific and is propelling the world towards a major food crisis. It’s not just that China has 1.3 billion people. It’s that so many of them have discovered sushi!

To make things worse, in addition to competing commercial considerations, China and its neighbours have sensitive political disputes over sovereignty claims – disputes that have resulted in large-scale environmental damage as claimants compete to strengthen shoals and reefs by dredging and reclamation on a huge scale and at the expense of regional security and stability.

Dead zones: How our oceans are losing their breath

Cyberspace and maritime space present tough issues, but they are important examples that remind us that strong institutions and international arrangements, which are valuable in the own right, also serve as a hedge against strategic rivalry.

Let’s make sure we distinguish between healthy competition, which tends to brings out the best in all parties, and strategic rivalry, which tends to bring out the worst

And let’s make sure we are distinguishing between healthy competition, which tends to brings out the best in all parties, and strategic rivalry, which tends to bring out the worst. No country benefits from US-China strategic rivalry.

Our approach to global governance has to be rooted in recognition that all of us share a deep interest in effectively managing global challenges: that means safeguarding cyberspace, sustaining the ocean’s resources, preventing macroeconomic instability and financial upheaval, promoting trade and investment, dealing with global public health risks like pandemics, slowing and mitigating climate change, countering weapons of mass destruction proliferation, and combating terrorism and piracy.

The US, China and the community of nations need to work in multilateral forums and work on multilateral instruments, both to prevent a dangerous future and to build a better one.

Daniel Russel, a former assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs at the US State Department, is currently diplomat in residence and senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute. This article is based on his speech last week at the annual China Conference hosted by the South China Morning Post