Don’t overlook methane emissions in the fight against climate change

Riccardo Puliti notes the progress in reducing carbon dioxide emissions, but say removing methane from natural gas production and use could also make a substantial difference, especially if the combined efforts of industry and governments pay off

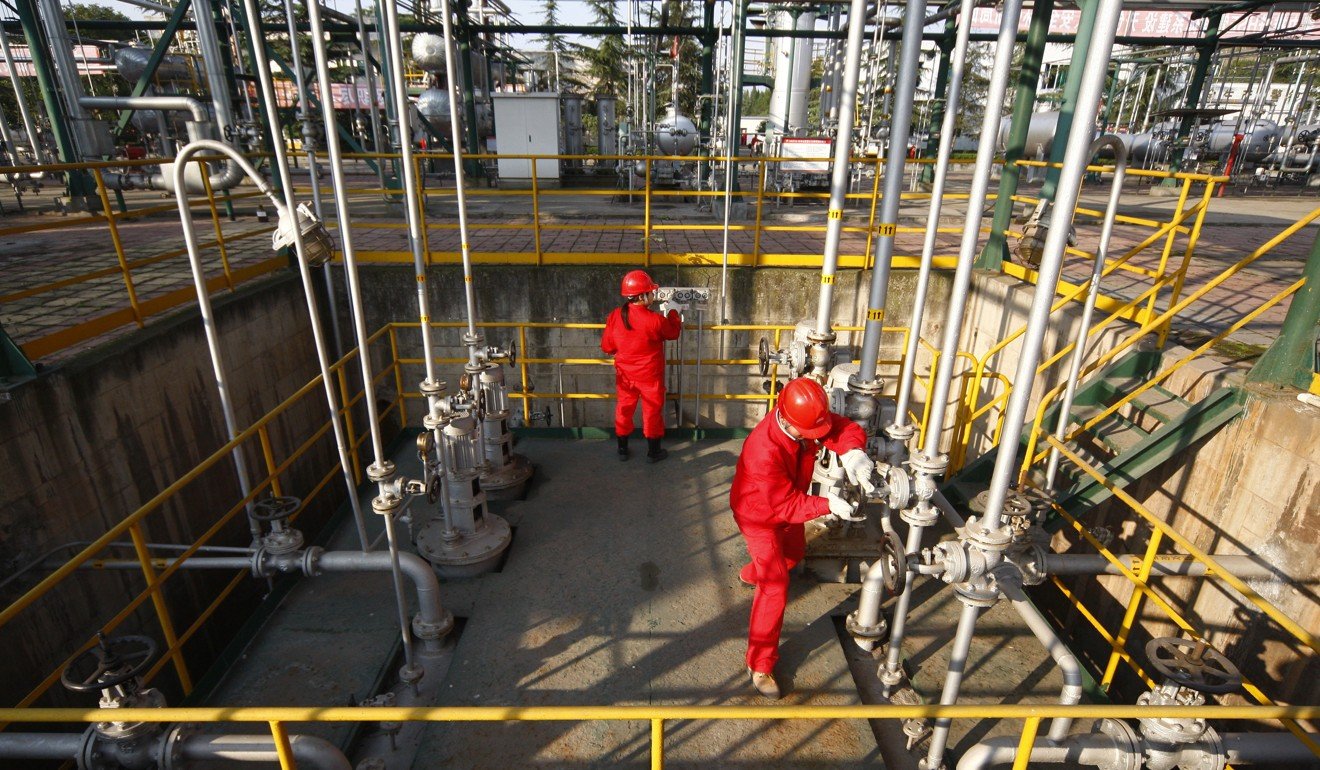

Natural gas is made up mostly of methane. At many points of the life cycle of gas, methane makes its way into the atmosphere – from extraction at a gas field all the way to the heating systems many of us have in our homes.

Natural gas is often referred to as a “transition fuel” – both because of the role it is able play in balancing wind and solar energy in electricity grids, and the assumption that its use will eventually decline as the world moves toward a low-carbon energy sector. It is entirely possible that, in electricity generation, renewable energy sources – backed up by batteries – may take natural gas’ share in the coming years if costs come down further.

How China’s highly polluting clothing industry is going green

The smart money is on food safety, health care, clean energy in China this year, say experts

‘There is a tipping point’: UN warns climate change goals laid out in Paris accord are almost out of reach

This is not going to be easy – methane is released at many stages of gas extraction, transport and production – from flaring at the wellhead to difficult-to-avoid leaks along long pipelines, to inefficient combustion in industrial plants and electricity generation. The good news is that the industry is very aware of the issue and is taking action – as individual companies and as a whole.

Last November, international gas companies gathered in London to work out a set of guiding principles to reduce methane emissions across the gas life cycle for the industry as a whole. For these companies, backing up gas’ reputation as the cleanest fossil fuel is going to require real, measurable reductions in methane emissions.

But the global gas industry cannot tackle this challenge alone. Emerging economies and developing countries, plus governments and national oil companies, need to do much of the heavy lifting. This requires long-term policy efforts and credible monitoring and reporting systems.

Success also requires sustained advocacy and campaigning by global civil society organisations that realise, no matter their position on natural gas, methane abatement has a huge climate upside. Experts and institutions also need to be involved to verify results and ensure the latest thinking and technologies are being brought to bear.

Alessandro Bisagni picks up the pace as the clock ticks down on climate change

Will China’s carbon trading scheme work without an emissions cap?

Such a global coalition to get methane out of energy production and consumption could, in a relatively short time, have a huge impact and make a tremendous contribution to tackling the overriding issue of our time.

Riccardo Puliti is the senior director for energy and extractives at the World Bank