Easing concerns of Hong Kong helpers should start with mandatory code

Following the latest decision by the High Court to uphold the live-in rule, officials must act to address the concerns of groups representing domestic workers

The top court ruled years ago that domestic helpers were not entitled to permanent residence because the live-in rule means they do not meet the requirement of being ordinarily resident in the city. Now, in the High Court, Mr Justice Anderson Chow Ka-ming has upheld the live-in rule, after a judicial review sought by a helper who claimed to be suffering acute stress as a result of her living conditions. He said a helper could always quit her employment.

So where now for helpers who have not only lost the argument that the rule violates their fundamental human rights, but also claim it exacerbates cases of ill-treatment, exploitation by employment agencies and some employers and poor living conditions?

Quitting is a drastic step after having come so far from home for work, and a risky one for those who are sole family breadwinners and have often run up huge employment agency debts.

The live-in rule was introduced in the early 2000s to help prevent job opportunities for local residents being taken by helpers seeking part-time work. But the number of helpers arrested for working illegally has remained small and static while their population has risen from 200,000 to 350,000. That means either the rule is a very effective deterrent or, more likely, unnecessary for the declared purpose.

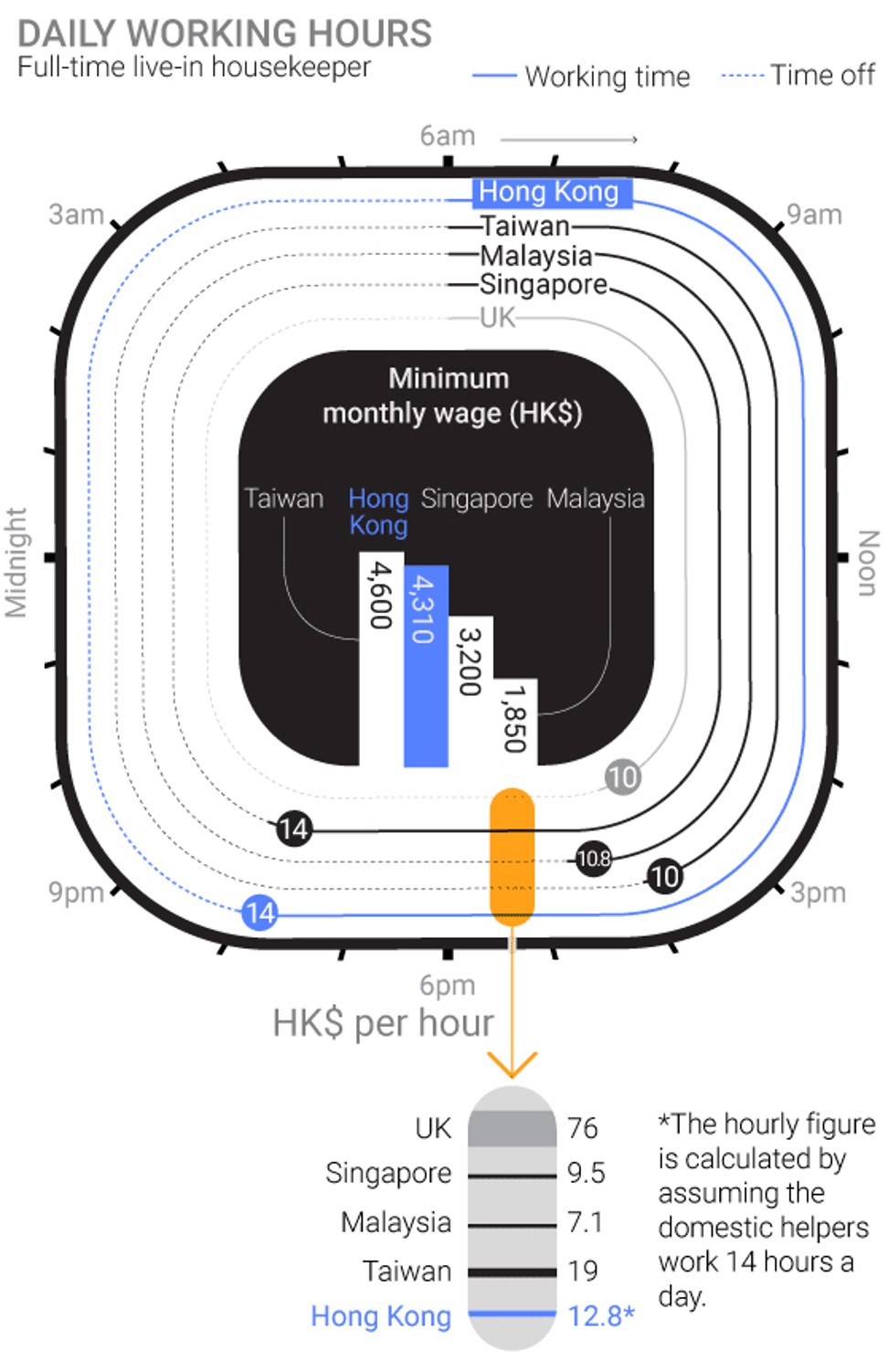

The argument against the live-in policy is that where helpers are at risk of abuse, exploitation and invasion of privacy, it leaves them even more susceptible. The wrongdoings of a small minority of employers may not do justice to the majority, but publicity of recent high-profile abuse cases does not help. Anecdotal evidence suggests that flagrant disregard for employee entitlements regarding working hours, rest days and public holidays is not uncommon.

The government says lifting the rule could have social and economic repercussions. These fears have to be set against the social and economic importance of such a large domestic labour force. Treatment of helpers as second-class citizens is not easily reconciled with trust in them to care for children and the elderly.

While the court has upheld the rule, the decision does not prevent officials from considering more proactive steps to address the concerns of helper organisations. After all, only last year they acknowledged serious problems by introducing a voluntary code of practice for employment agencies to protect helpers from abuse and exploitation such as charging grossly excessive fees, creating indebtedness that does no good to employer or employee. Making the code mandatory and compliance accountable to the legislature would be a good first step towards doing justice to the role helpers seem destined to play in our everyday life for a long time to come.