Kim Jong-un can’t just wish away US role on the Korean peninsula

John Barry Kotch says if a summit of the two Koreas is to succeed where others have failed, negotiations must go beyond the basis of ‘no testing, no exercises’ to consider US deployment in South Korea – with the proviso that the North Korean leader gets a better grasp of history

The two huge choices for Moon Jae-in to keep Olympic peace

What message is being sent via Kim Yong-chol? Presumably, it will centre on the content of a future summit, against the backdrop of rising tensions on the Korean peninsula over the North’s nuclear programme.

Renewed missile testing by Pyongyang or joint military exercises by Seoul and Washington would almost certainly scuttle any meeting. Therefore, setting down a date or a time frame – say, early summer – would have the advantage of “locking in” several more months of a de facto freeze while giving more time for diplomacy to gain traction.

It’s hard to know whether the North-South political divide can be bridged by momentum generated by an Olympic high, whether it represents a new start or merely a divertissement.

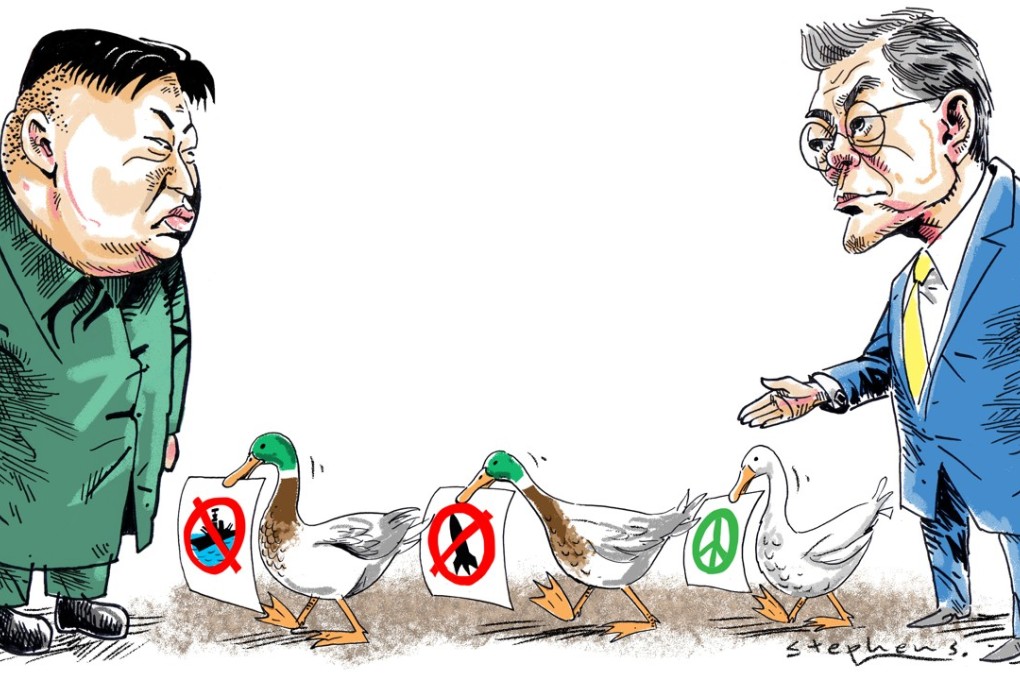

But, before responding to North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s invitation for a summit meeting in Pyongyang, Moon needs to have all his ducks in a row, carefully studying the record and results of the two previous summit meetings held by former presidents Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun, in 2000 and 2007 respectively. Both were long on ceremony and short on substance.