Kim Jong-un can’t just wish away US role on the Korean peninsula

John Barry Kotch says if a summit of the two Koreas is to succeed where others have failed, negotiations must go beyond the basis of ‘no testing, no exercises’ to consider US deployment in South Korea – with the proviso that the North Korean leader gets a better grasp of history

The two huge choices for Moon Jae-in to keep Olympic peace

What message is being sent via Kim Yong-chol? Presumably, it will centre on the content of a future summit, against the backdrop of rising tensions on the Korean peninsula over the North’s nuclear programme.

Renewed missile testing by Pyongyang or joint military exercises by Seoul and Washington would almost certainly scuttle any meeting. Therefore, setting down a date or a time frame – say, early summer – would have the advantage of “locking in” several more months of a de facto freeze while giving more time for diplomacy to gain traction.

It’s hard to know whether the North-South political divide can be bridged by momentum generated by an Olympic high, whether it represents a new start or merely a divertissement.

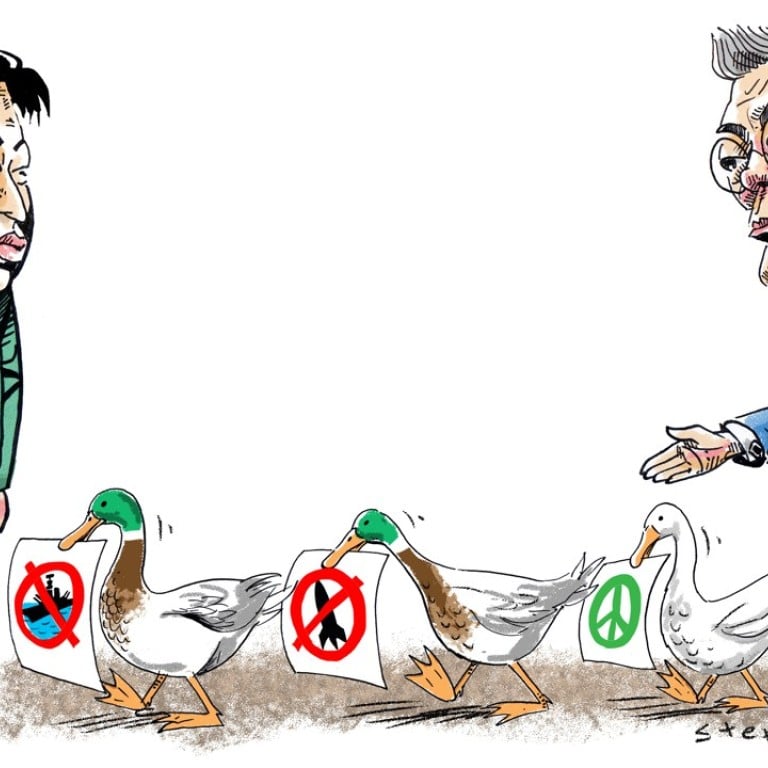

But, before responding to North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s invitation for a summit meeting in Pyongyang, Moon needs to have all his ducks in a row, carefully studying the record and results of the two previous summit meetings held by former presidents Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun, in 2000 and 2007 respectively. Both were long on ceremony and short on substance.

North Korea ‘ready’ for talks with US

If and when a North-South summit were to take place, a key goal should be to probe Pyongyang’s willingness to re-examine the historical narrative on which successful negotiations depend. In short, any summit meeting will involve something of a history lesson for the young North Korean leader, who needs to be disabused of any notion of driving a wedge between Washington and Seoul.

US and South Korea hold massive air exercise in December 2017

The long-standing US military footprint on the Korean peninsula is another staple of North Korean propaganda, allegedly the reason Korea remains divided. In fact, while past US administrations of both political parties have crafted far-reaching proposals at several reprises addressing this, Pyongyang has consistently rejected such initiatives.

The US can’t be written out of the security equation on the Korean peninsula

Thus, for example, former secretary of state Henry Kissinger’s 1974 proposal for “alternative armistice arrangements” provided for US troop withdrawal, with the caveat that a small continent of US forces would remain “until the security situation stabilised”. China supported the initiative but the North Koreans baulked. Similarly, president Jimmy Carter‘s controversial proposal to withdraw US ground forces over a five-year period was derailed by Kim Il-sung’s concurrent increase in the strength of North Korean troops.

If negotiations were to resume on a “no testing, no exercises” basis, a trade-off involving the redeployment and/or partial withdrawal of US forces, in exchange for Pyongyang’s removal of long-range artillery trained on Seoul, could be on the agenda.

Further, multilateral security guarantees by the outside powers, principally the US and China, could be added to the mix, complementing and eventually replacing the bilateral security commitment.

US-South Korea military drills to go on despite Pyongyang’s charm offensive

Finally, on a strategic plane, while deterrence of the North and defence of the South has prevented a resumption of fighting since the 1953 armistice, peace and security remains precarious with the escalation of the nuclear crisis and the war of words between Washington and Pyongyang. The latter has held the South Korean capital, Seoul, hostage with long-range artillery, with its “bee sting” strategy – that is, the enemy dies first, even if it must suffer the same fate.

John Barry Kotch is a political historian and former State Department consultant