Though cyberattacks now occur with greater frequency and intensity worldwide, many either go unreported or under-reported, leaving the public with a false sense of security. While governments, businesses and individuals are all targeted, infrastructure has become the choice for both individual and state-sponsored attackers, who target security systems previously seen as impenetrable. This shows the vulnerability of cities, states and countries and the importance of global risk agility.

The

US now blames

Russia for cyberattacks on

energy,

aviation and other sectors in recent years. Moscow planted malware, conducted spear phishing and gained remote access to sensitive areas of America’s infrastructure networks. They did this with surprising ease; for example, using false résumés to apply for jobs and installing malware once tainted emails were opened.

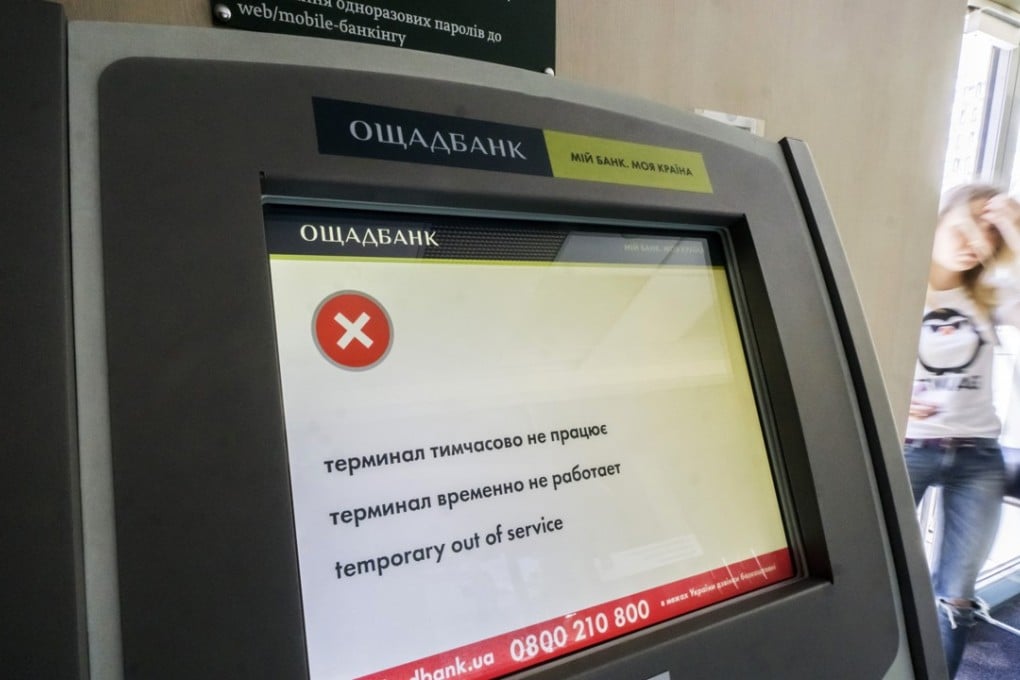

This modus operandi is not new to Russia or others intent on planting malware and gaining entry into sensitive companies and sectors. Russia planted the malware leading to

the Petya attacks of 2017 by entering a Ukrainian tax and accounting firm servicing 80 per cent of

Ukraine’s businesses, then gaining access to those businesses. This quickly infected computers around the world.

It is shockingly easy to enter otherwise secure computer systems and companies. Up to 95 per cent of the time this is because of the risk between keyboard and chair – employees who click infected links.

Cyberattacks are difficult to prevent, given the relative ease with which hackers can find a single system vulnerability, and the impossibility of plugging all security holes.

Cybersecurity professionals play an endless game of cat and mouse, where would-be attackers attempt to enter a system while security professionals attempt to defend it by applying continuous patches. The adversary then quickly moves to another vulnerability. That is why many computer security programs produce patches numerous times per day.

High-profile cyberattacks are increasingly the norm, giving nations of all sizes, degrees of wealth and resources a seat at the table with world leaders in overt and covert cyberattacks.

Iran and

North Korea are prominent members of this club. All this has prompted the

Trump administration to declare that it equates cyberattacks against critical infrastructure as acts of war,

potentially resulting in a nuclear response.