Big Zucker is watching you: Facebook has realised Orwell’s dystopian vision, and we like it

Niall Ferguson says Facebook tracks our data, our smartphones track our movements, and Mark Zuckerberg has become filthy rich from that information

In George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, the telescreen is the primary tool of totalitarian surveillance. It is, in Orwell’s words, “an oblong metal plaque like a dulled mirror which formed part of the surface of the wall ... The instrument could be dimmed, but there was no way of shutting it off completely.

“The telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously. Any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up by it; moreover, so long as he remained within the field of vision which the metal plaque commanded, he could be seen as well as heard. There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment ... You had to live – did live, from habit that became instinct – in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinised.”

Winston Smith (“6079 Smith W”) knows to keep his back to the telescreen as much as possible and, when facing it, to wear an “expression of quiet optimism”.

“It was terribly dangerous to let your thoughts wander when you were in any public place or within range of a telescreen ... To wear an improper expression on your face was itself a punishable offence. There was even a word for it in Newspeak: facecrime, it was called”.

For most of my life, ever since I read Orwell as a teenager, I have thanked God that I didn’t end up as a citizen of Airstrip One, living my life as a helot in thrall to Big Brother. It was not long after the actual year 1984, when I made my first visit to the Soviet Union, that I realised a significant part of humanity was in precisely that situation.

Here’s how to see which apps have access to your Facebook data — and cut them off

The Soviets lacked the technological skill to create the telescreen, but their system of surveillance – based on countless concealed microphones and cameras – did the job. Everything else about Soviet life was straight out of Nineteen Eighty-Four, particularly the disconnect between the strident propaganda (the pig-iron statistics and the military parades) and the dispiriting shabbiness of everyday life. How relieved I felt to return to capitalism and democracy.

Forget Facebook: Here are six other apps for staying in touch with friends

BBC: “And you won’t sell it?”

MZ: “No, of course not.”

This was a disingenuous reply. To be sure, Zuckerberg has not – strictly speaking – sold Facebook users’ data. But he did not become a multibillionaire because all two billion users mailed him US$20 to say: “Thanks for making the world more connected.”

In 2007, Facebook allowed users to build apps within its site – a decision that proved hugely popular as Facebook-based games proliferated. At the same time, users could sell their own sponsored advertisements.

Facebook saga sends out insecure message

The crucial difference was that Google simply helped people find the things they had already decided to buy, whereas Facebook enabled advertisers to deliver targeted messages to users, tailored to meet the preferences they had already revealed through their Facebook activity. Once adverts were seamlessly inserted into users’ news feeds on the Facebook mobile phone app, the company was on the path to vast profits, propelled by the explosion of smartphone usage.

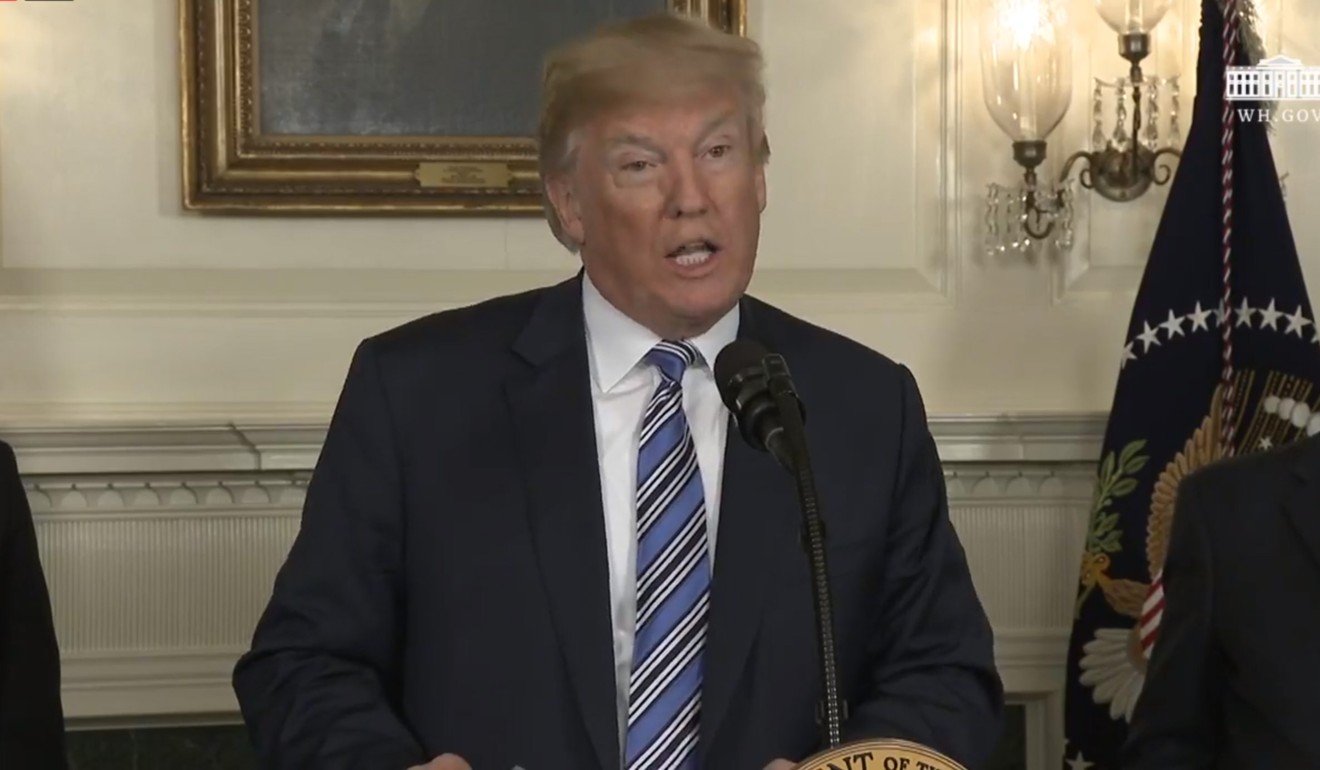

Trump campaign data firm Cambridge Analytica suspends CEO after boasts of entrapping politicians with bribes and sex

It took torture – followed by copious amounts of gin – to finally convince Winston Smith that “he loved Big Brother”. In that respect, too, Zuckerberg has gone one better than Orwell: “It was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He liked Big Zucker”.

Niall Ferguson’s The Square and the Tower will soon be available in paperback from Penguin