There is a certain inevitability about China’s need for

North Korea and the North’s need for China. The two may intuitively hate each other, but they can’t stay apart in the regional tug of war. It’s been that way ever since Chinese forces poured into North Korea several months after the North Koreans invaded

South Korea in June 1950, to stave off the Americans who had reached the Yalu River that flows between North Korea and China.

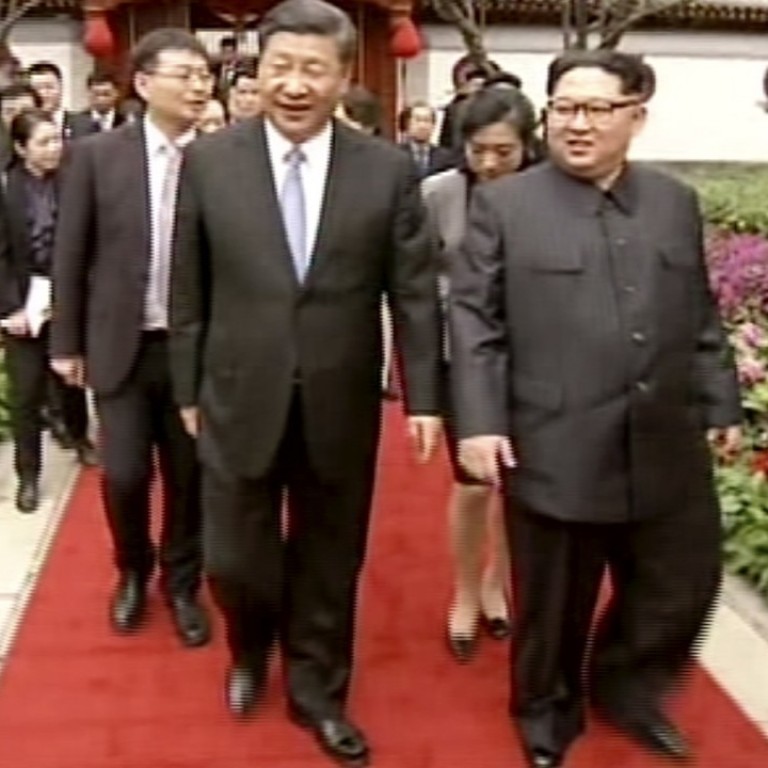

Now, as the Chinese and Americans again face one another in a stand-off that seems likely to worsen, President

Xi Jinping has received Kim Jong-un on a historic mission from North Korea, despite misgivings about Kim’s nuclear programme. Xi may have hitherto ignored Kim as a supplicant, but ugly realities dictated a change of heart.

One reality is that

America, under President

Donald Trump, is raising the spectre of a

trade war with

new tariffs aimed largely at China, on top of military confrontation all around China’s rim. Could it be coincidental that a

special North Korean train – not seen in Beijing since Kim Jong-un’s late father Kim Jong-il bowed before China’s leaders in several visits to the Chinese capital – arrived in Beijing so soon after Trump announced his tariffs?

And why would Xi receive any delegation from North Korea if he was not also interested in shoring up China’s defences along a vulnerable frontier that remains a barrier to US power? US forces again teaming up with the South Koreans in annual war games is just one annoyance. China also has to consider

Japan’s moves to the right under Prime Minister

Shinzo Abe, who has advocated

revising Japan’s post-war “peace” constitution banning Japanese forces from joining in foreign wars.

China’s concerns, all around its periphery, are most clearly acute in the

South China Sea to which the Chinese steadfastly claim rights of ownership. The Chinese media issued taunts as the US aircraft carrier Carl Vinson showed the American flag in those waters after calling at Da Nang, the port city in central Vietnam where US marines were headquartered during the Vietnam war.

By inviting Kim to Beijing, Xi clearly felt the need to make sure he’s on the same wavelength as the North Koreans. Kim had to have intimated what he plans to say when he meets South Korean President

Moon Jae-in in the truce village of Panmunjom

next month, and maybe Trump the month after.

And, just as he did to a South Korean delegation that called on him in Pyongyang after the

Pyeongchang Winter Olympics, Kim expressed to Xi his

“willingness” to abandon his nuclear programme. North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests may not set off alarm bells in Beijing as loudly as they do in Washington, but Xi pointedly stressed the need for “denuclearisation”, as indeed have both the American and South Korean presidents.

But why did it seem necessary for Kim to go to Beijing to hear all that from Xi, when previously Xi was accustomed to sending emissaries to Pyongyang to register his discontent and try to bring the North Koreans into line? On his first trip outside North Korea since taking over after the death of his father in 2011, Kim clearly had another priority. He has to get North Korea out from under the onerous

sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council – with China’s consent – after North Korea’s nuclear and long-range ballistic missile tests.

Xi, in turn, might lavish gifts on the North Koreans. Just imagine how much the North has been hurting while China abides by sanctions, curtailing the flow of oil that North Korea needs to fuel its decrepit economy and cutting off the import of North Korean coal. China has hitherto made a show of going along with sanctions, but Trump’s tariffs may be more worrisome to the Chinese than North Korea’s nukes.

Having slowed the flow in conformance with sanctions, Chinese bureaucrats at Xi’s behest should suddenly be able to provide the aid, comfort and oil the North Koreans need while the Americans and South Koreans play their annual war games close to the line with North Korea – and not that far from Chinese territory, too.

Donald Kirk is the author of three books and numerous articles on Korea