Space lab’s fiery end a sign of China’s rise

Tiangong-1 was a crucial element of China’s learning curve in space exploration. And while the United States and Russia have the lead after many more decades of research and experience, China is catching up in leaps and bounds

Space debris the size of the Tiangong-1 laboratory returns to Earth only now and then, so eyes were cast skywards in anticipation of a fiery show on April 1. As it was, the craft proved elusive, breaking apart and burning up in the atmosphere above the remote reaches of the southern Pacific Ocean.

But whether the pieces were seen or not, it reminded the world that China’s presence in space mirrors the nation’s economic and political rise.

The United States and Russia have a lead and understandably so given their many more decades of research and experience, but China is catching up in leaps and bounds.

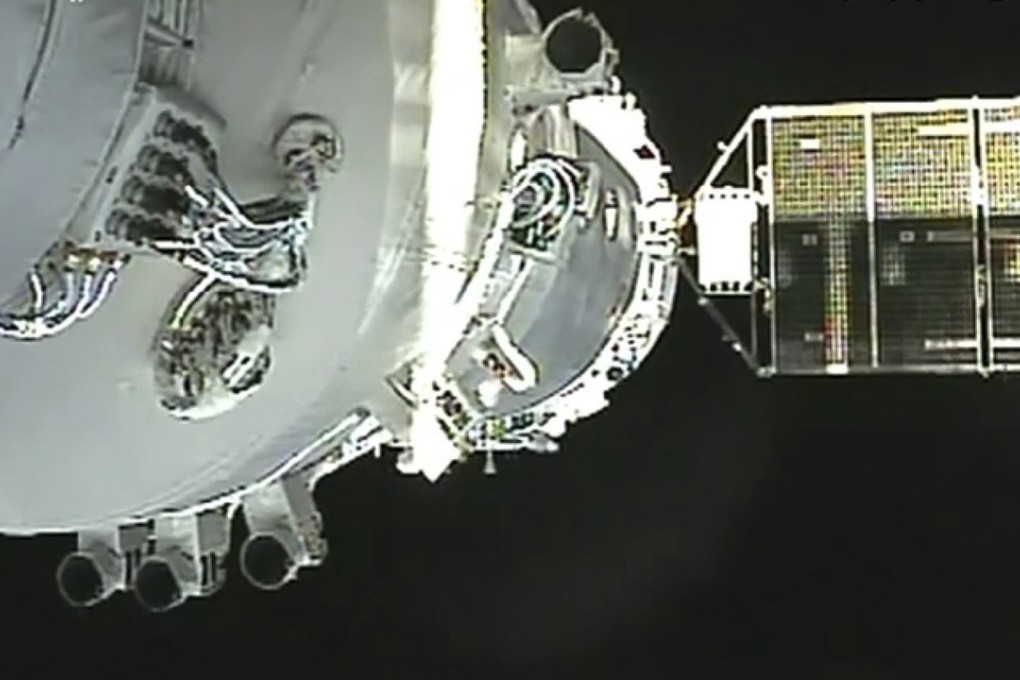

Tiangong-1’s main mission was about helping China gain expertise in building, operating and maintaining a space station. Beijing, shut out of involvement with the much larger International Space Station by the United States, had no choice other than to construct its own. A two-module experimental facility with an anticipated lifespan of two years was started in 2011 and after two visits by astronauts and numerous experiments, communication was lost in 2016. A new space station is being built and expected to be operational by 2022.

But Tiangong-1 was a crucial element of China’s learning curve, enabling the first-ever orbit and docking by a robotic spacecraft, the Shenzhou-8, and then the linking of the crewed Shenzhou-9 and its three occupants going on board. Those strides have increased China’s confidence and ambition. With the powerful Long March rocket at the Chinese space programme’s core, a second lunar mission is planned for later this year with a lander to put a rover on the far side of the moon.