Why a US-China trade war is self-defeating in a connected world

Liu Jun says most goods and services rely on a vast network of trade relationships benefiting people worldwide, and technological breakthroughs will bring disruptions that require societies to work together to find solutions

Although globalisation might not be a buzzword any more after the backlash of populism and nationalism, the trend of being more global than local is still in motion, in spite of some hitches along the way. So how could a trade war take place in this era of a digital economy and the “internet of things”?

A trade war is definitely a misnomer. Here are some reasons why.

First, the world economy has become an intertwined system. The theories of comparative advantage and value chains were based on outdated experiences of the past millennium. Today, the value system has replaced the value chain and stretches to almost every corner of the globe, weaving together various industries, diverse factors of production and an enormous pool of human talent. People find it very challenging to identify the country of origin of a product or service, along with the capital and labour embedded within it.

The resources and even risks from economic activities are allocated and dispersed worldwide, and people move all over the place. To be sure, a few things are still too localised to be exported overseas, but they are very few these days, given that even traditional foodstuffs such as sushi and tofu have made it abroad.

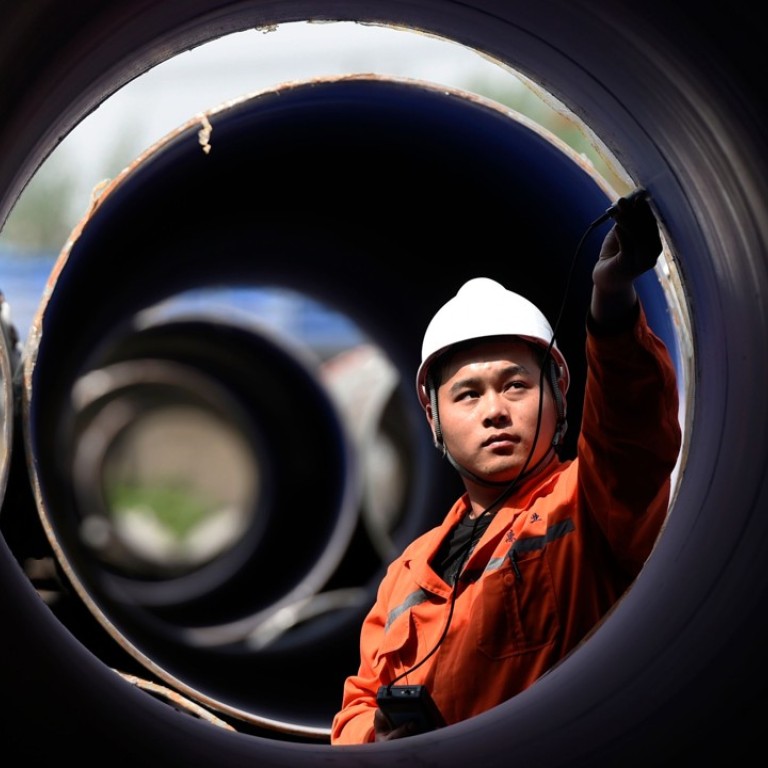

Almost every single tradeable product has both local and foreign, or national and international, elements. When a product is being manufactured in one country, some parts always come from other countries, or the manufacturer itself is a foreign or joint venture.

When a government levies heavy tariffs on certain goods, it is potentially a punishment for all the parties operating in a worldwide value system. Attacking any single part will no doubt affect the whole system through ripple and domino effects. Therefore, multilateral treaties are in fact a value-system-based arrangement and we should be encouraged to comply with them.

Second, national security issues can only be addressed internationally – not by imposing man-made obstacles on trade and investment flows, but by taking common threats seriously, in unison. So far, there is no empirical evidence suggesting even a small significant correlation between trade and security threats.

Importing or exporting equipment or goods – even hi-tech products – surely benefits people of the countries engaged in the trade. If the well-being of the people is substantially improved by trading with one another, how will that agitate security threats towards their countries?

National security risks are contingent on poverty, not social well-being. If wealth is created through production and consumption, and prosperity is achieved through distribution and sharing, national security would no doubt be self-fulfilling and self-sustained.

Therefore, restricting or blocking certain imports – in particular technological elements – does not help security; and slapping huge tariffs on goods from other counties in the global value system would fail to benefit those who started the vicious cycle.

These new technologies render national borders irrelevant, bit by bit. Take cloud computing and storage for example; the cloud does not belong to any single sovereign state, no matter how powerful or powerless.

These new technologies render national borders irrelevant, bit by bit

These are some of the reasons against any impulsive multilateral trade conflict. There are many more, and they all come to the same conclusion: war-war is out of the question, jaw-jaw is not so good, either. In fact, “coopetition” is the future of global trade and investment interactions.

We hold the key to the challenges in a new era.

Liu Jun is a member of the China Finance 40 Forum