How to privatise Hong Kong’s public housing, and satisfy the desire for homeownership

Richard Wong says people’s aspirations for homeownership can’t be ignored. A plan to let public tenants buy their flats could succeed if the prospective owner has a realistic chance of paying off the loan, and is able to reap the full capital appreciation of the property

Hong Kong’s public housing policy was devised in the 1970s when the main housing problem was overcrowding in the private rental sector. Many of the tenants had very low incomes and it made sense for policymakers to focus on affordable low-rent flats.

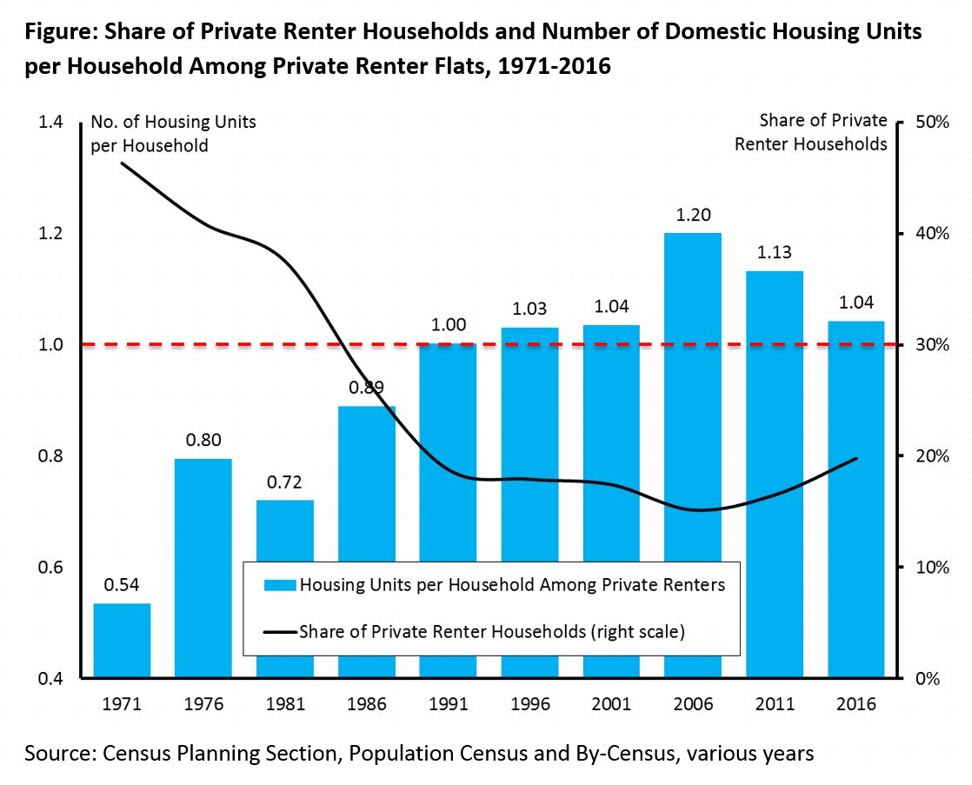

By the 1990s, however, the situation had changed completely. The number of units per household among private renters had increased from 0.54 in 1971 to 1 in 1991. Overcrowding had mostly been eliminated and improved economic conditions had increased the attractiveness of homeownership.

Unfortunately, the original public housing strategy did not change under these new circumstances. There was no systematic review to reprioritise it from a tenancy-based model to an ownership-based one – with the possible exception of the ill-fated and flawed Tenants Purchase Scheme, which was launched in 1998 and discontinued eight years later.

Today, as private home prices continue to rise, a shortage of affordable private rental housing has led to the mushrooming of subdivided units. As a result, more households are opting for the more spacious and more affordable public rental flats.

I believe this situation has obfuscated the real housing issue, which is the unsatisfied demand for homeownership.

The real housing issue ... is the unsatisfied demand for homeownership

The high down payment and high land values have made it extremely difficult for those with modest means to own a home in prosperous Hong Kong. But we can do something about this. I propose a method to sell new public flats and privatise the existing stock that would be fair to everyone and would not encourage a nanny state.

This proposal involves dividing the market value of public flats into the development cost and land value.

The Housing Authority could offer public flats for sale to eligible households at a price that would cover the cost of development, say, HK$1 million (US$127,000) with a 5-10 per cent down payment. The household could then apply for a mortgage loan from a bank, backed by a government guarantee, as is the current practice with Home Ownership Scheme flats. The successful occupant would not be allowed to transfer ownership of the flat to another person or group for the first five years.

The outstanding land value owed to the government would be calculated based on the average market value for that site over the past 10 years, to smooth out fluctuations. Repayment of the land value would not kick in until after the five-year moratorium is up, and would incur an interest charge of 2 per cent.

My proposal means that the government becomes a creditor instead of a joint equity holder in the flat. It could also perform an insurer’s role if a household’s financial circumstances deteriorate unexpectedly, by allowing the owner to service the interest charge on the outstanding loan without paying down the principal.

This arrangement should give hope to the owner that there is a realistic chance of repaying the loan eventually, and allow them to reap the full capital appreciation of the property.

I realise there would be objections.

I have heard it argued that the middle class would object to giving low-income households such a lucrative deal, but this is based on a false premise because the land value and development cost are currently not recovered in the rental charges of public rental flats. The middle class is already paying for public housing through taxes.

Furthermore, the flats would not be sold at a discount to the market, but at a price averaged over 10 years to remove business-cycle price fluctuations.

Others say the government should not encourage low-income households to take unusual risks, as the property market may well crash. But the substantive threat of foreclosure and an inability to reschedule debt payment can be resolved if the government is the creditor.

A third objection stems from the government’s experience in operating the Tenants Purchase Scheme, which allowed tenants to buy their flats over 10 years. The scheme is a management nightmare, since owners and renters can be found in a single building. Moreover, owners generally do not see their units as fully owned, since the unpaid premium is so unaffordable. The interests of owners and renters are not well aligned. My proposal provides a way of resolving this problem.

A programme that facilitates flat sales would revive hope for both the low- and middle-income groups and make better use of scarce housing resources. It would be sustainable, and help narrow the economic and social divides in Hong Kong.

Refocusing public housing policy towards homeownership would, however, represent a major policy shift.

Why is it imperative that the government does so today? And what would happen if it fails to do so? This is the subject of my next article.

Richard Wong is professor of economics and Philip Wong Kennedy Wong Professor in political economy at the School of Economics and Finance at the University of Hong Kong