Advertisement

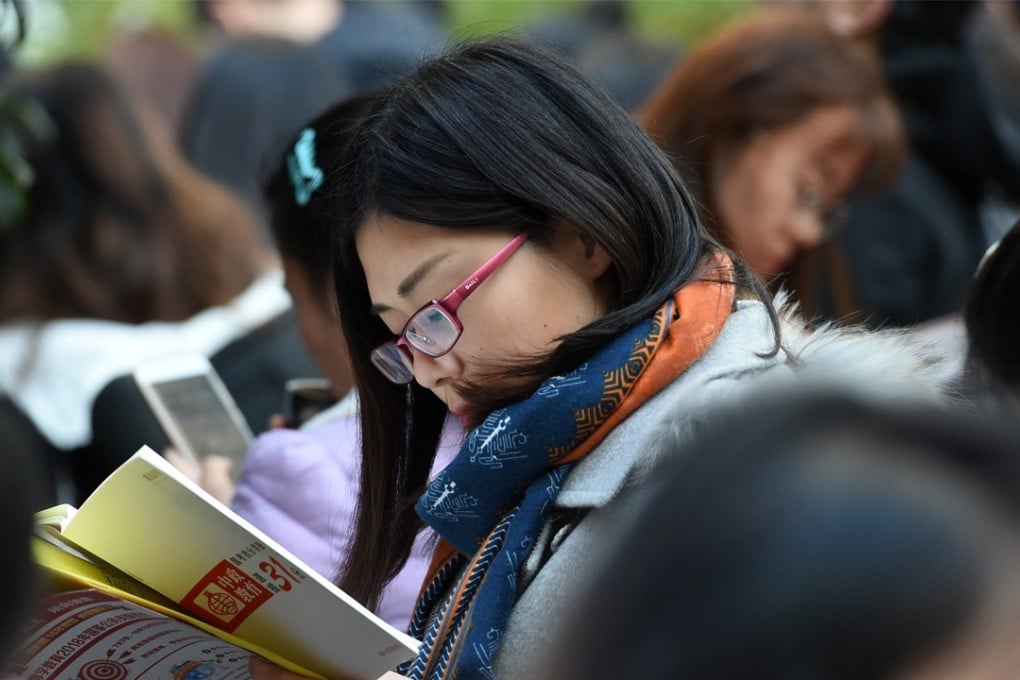

Gender discrimination in China is resurfacing as employers seek pretty women, or men

Lijia Zhang says China’s economic development has brought back regressive ideas about women – evident in sexist job adverts – that is fuelling a widening gender pay gap

3-MIN READ3-MIN

“Looking for a pretty female, must be taller than 1.70 metres, with fine features.”

This is not a personal advertisement but a job posting for a salesperson. I came across it some 22 years ago when I reported on a job fair in Beijing. It was the first time I noticed such blatant sexism in recruitment advertising. Having grown up with Mao’s declaration that “women hold up half of the sky”, I was shocked.

Sadly, gender discrimination has worsened. A recent Human Rights Watch report on gender discrimination in employment in China finds widespread prejudice in recruitment advertisements. For example: “Woman must possess female beauty that exceeds nature itself” and, “Beautiful girls needed.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x