Advertisement

Why Hong Kong’s coding classes and tutorials will not nurture the next Steve Jobs, but engaged parenting might

Robert Badal says contrary to the myth of the ‘digital native’, today’s children, like their predecessors, learn best from interactions with their parents

4-MIN READ4-MIN

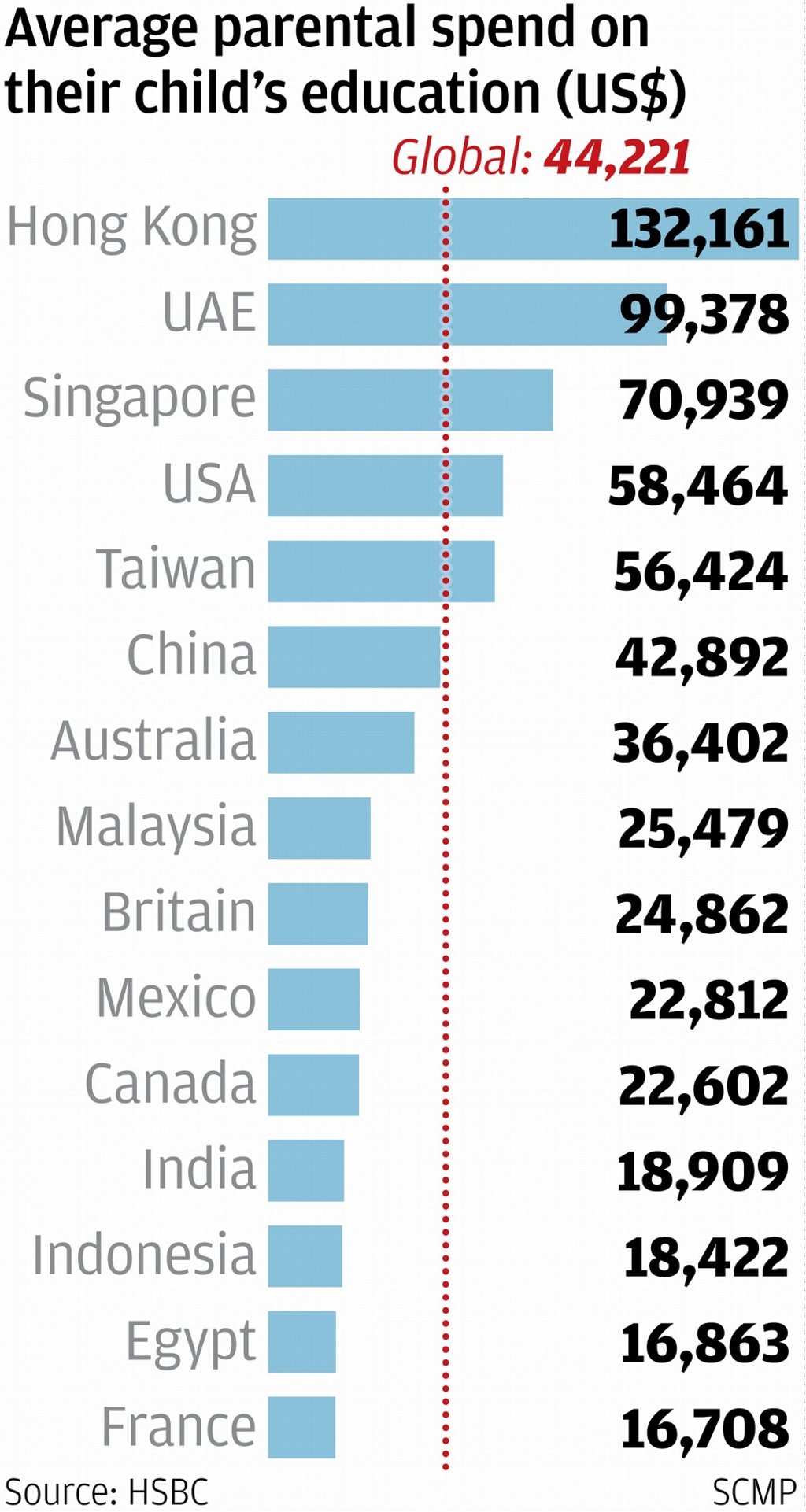

Hong Kong parents are educational spending champions. This is manifested in “delegated parenting”: sending children to tuition schools. Family time that involves shared learning experiences is rare, arguably, due to long working hours. However, they spend more than anyone else in the world, so this argument seems circular.

Hong Kong’s tuition school spending is not guided by knowledge about education or parenting, only trendy marketing: last year, English drama, this year, coding classes.

The latter is a mystery to me, given that Hong Kong’s information technology workers are facing lay-offs. I get constant emails offering “Lowest Price!” on coding. Recently I needed some HTML work done. I sent off replies to see what the “lowest price” would be. What was it? Free! Three of the desperate firms offered to do it gratis to “show me what they could do”.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x