Why a new housing plan for squatters signals a radical change in Hong Kong governance

Bernard Chan says the government’s offer of more generous compensation to try to speed up new town development represents a break with its long-held principles of safeguarding taxpayers’ money, and is a sign officials are ready to move with the times

The issue of long-term land supply in Hong Kong – as with so many of our basic challenges – seems to come down to a long list of unsolvable problems.

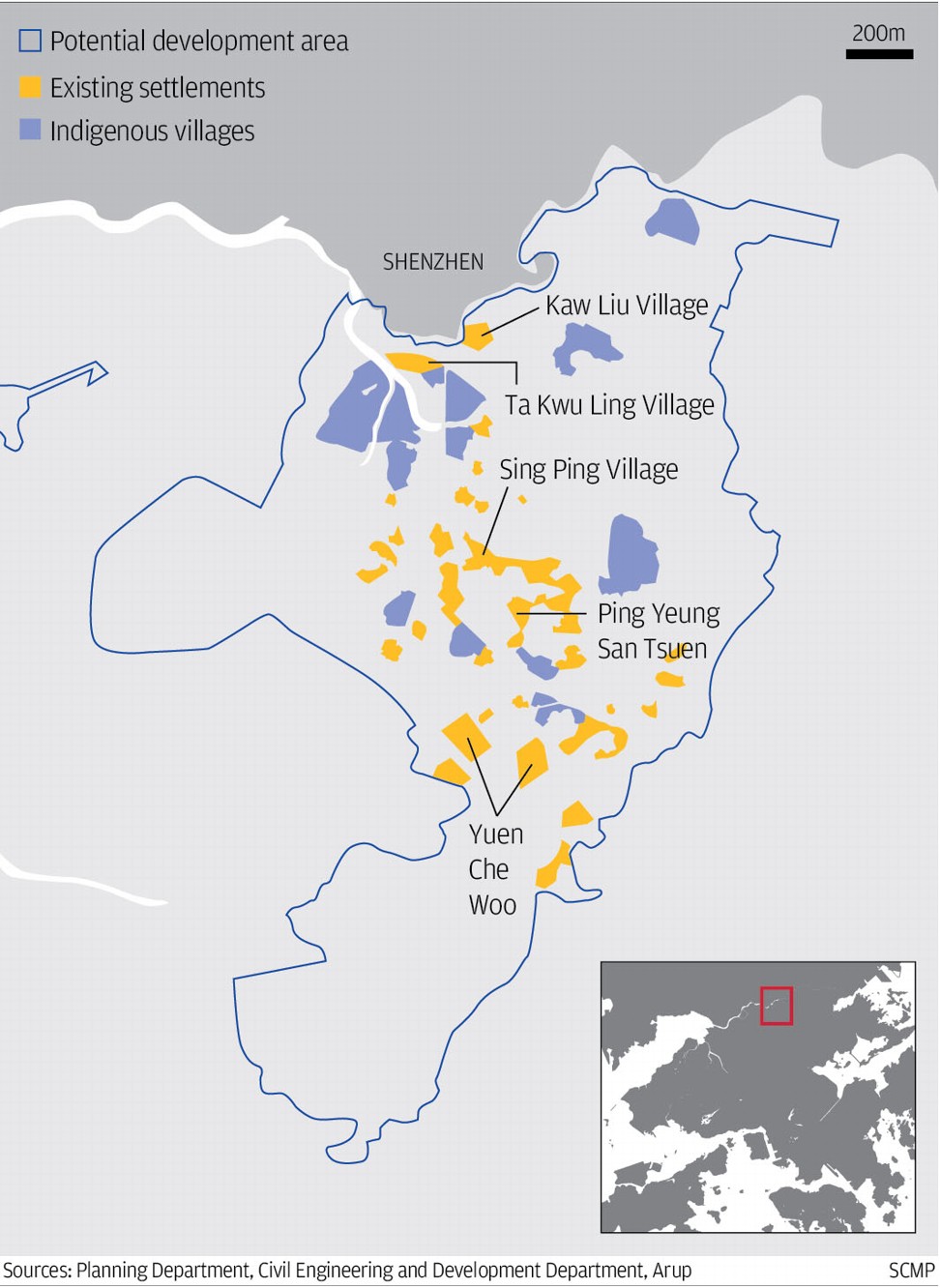

If the government’s new approach to squatters overcomes the current opposition, it will help speed up the release of hundreds of hectares of land for new housing. More importantly, officials’ willingness to be flexible – even take some risks – suggests that our bureaucracy can adapt to new thinking in other policy areas.

Up to now, the policy has been to offer limited compensation to residents of squatter areas being cleared. For example, the government would offer ex gratia payments only to those who had established 10 years’ continuous residence in registered domestic structures. Households would be eligible for rehousing only on a means-tested basis.

There is a fear that people will find a way to cheat if the government offers generous inducements to solve problems

This fairly strict approach was for a good reason. If new arrivals were eligible for compensation, it would provide an incentive for more people to move into squatter housing to get the resettlement benefits – at the expense of taxpayers and other people waiting for public housing.

However, the squatters have vigorously demanded more generous arrangements, and public opinion has been mixed. Some people sympathise with the squatters, while others oppose rewarding people occupying land illegally.

Officials were left with a choice between evicting a relatively large number of squatters, with all the controversy that would go along with it – or leaving the problem aside and delaying the supply of land.

The government has done neither; instead, it’s offering a more generous package. Periods of residence have been lowered, and more households will be eligible for financial compensation – the amount of which will also be raised – or for housing without means-testing. This will raise the number of households in squatter areas eligible for the main resettlement benefits from about one-third to two-thirds.

Clearly, this is a flexible and pragmatic approach.

Although it might seem like a relatively small or obvious concession to make, it represents a shift in traditional official thinking. Essentially, this solution breaks with some strict principles on safeguarding taxpayers’ money and public housing. Instead, it gives more weight to less-quantifiable factors like people’s expectations and the community’s sense of fairness – and of course speedy results.

It is not intended to be a one-off arrangement, but will be applied to other comparable situations in future.

Some people might say this is simply overdue and wonder why it’s a big deal. But some of our officials probably see such a move away from established principles as risky.

It involves being more relaxed about using taxpayers’ money and other resources. It could raise complicated questions about fairness. Why should squatters deserve more help with housing than others who are in need? Why should law-abiding people subsidise lawbreakers?

Watch: How a village is using paint brushes to fight Hong Kong redevelopment plans

It could also raise expectations among other people who are occupying illegal premises – say rooftop structures or subdivided flats – or who are benefiting from some other tolerated loophole. And there is a fear that people will find a way to cheat if the government offers generous inducements to solve problems.

To use civil servants’ language, it has “cost implications” and it could open the floodgates.

In the specific case of squatters and land supply, we can justify more flexibility because the costs of delay will be far greater. But we should not underestimate the importance of this change in traditional bureaucratic thinking.

Officials themselves are even using the term “people-oriented” to describe this new approach. Critics might mock this. But it is a sign that the government realises times are changing and it has to break with long-held principles.

Bernard Chan is convenor of Hong Kong’s Executive Council