Why Zhuhai and other Greater Bay Area cities are not to Hong Kong what suburban Connecticut is to New York

Hua Guo and Victor Zheng say the suggestion that Hongkongers move to the Greater Bay Area and commute to the city ignores the disparity in legal institutions, political rights and social services among cities in the region

A survey by the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies found around 60 per cent of respondents between 18 and 30 disagreed with the feasibility of relocating to Zhuhai after the commissioning of the bridge. All other age groups also held a negative view of the feasibility of relocation.

Hong Kong’s elites are advocating American-style suburbanisation in which the population lives in the suburbs and commutes to work downtown. Affordability and social stratification underlie this process.

For example, rapid suburbanisation in the US after the second world war came with a boom in home ownership among white-collar families. Affluent families moved out of downtown to enjoy improved living conditions in suburbia. The working classes that found it difficult to afford a suburban life were confined to a downtown abandoned by the middle class.

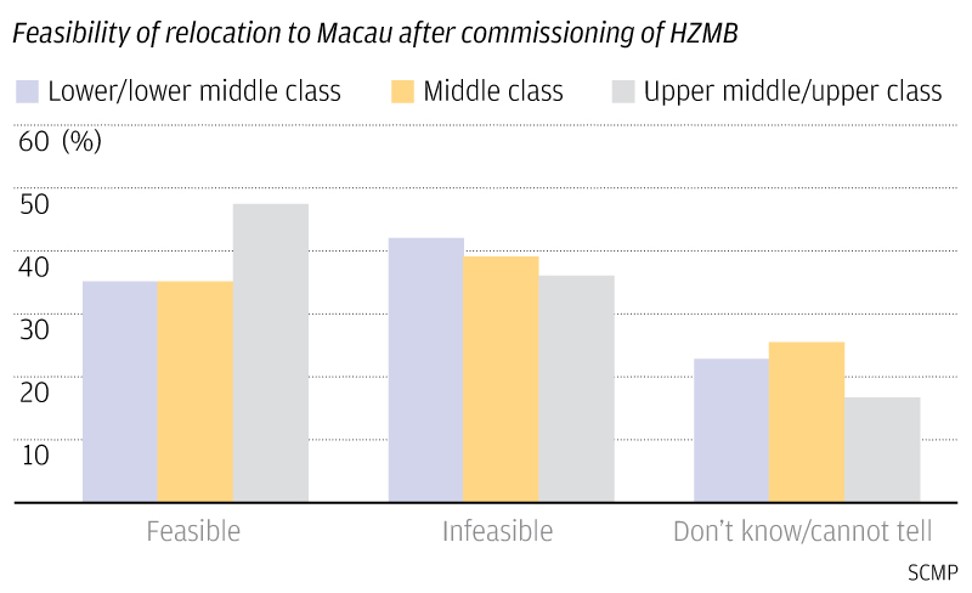

The breakdown of views on the feasibility of relocation to Zhuhai by social class in the survey indicates that the upper-middle or upper classes were equally split on the feasibility of moving to Zhuhai. But a greater proportion of middle-class and working-class people felt moving was unfeasible. The results suggest people’s confidence in moving differed according to social class: the working class and even the middle class were less confident about relocating than the very limited number of upper-class people.

Those who proposed the suburban model disregarded the fact that movers usually look for a familiar social or institutional context. Cities in the New York metropolitan area, though covering three states, have similar institutions. Commuters do not need to worry about the discrepancies in the legal system or entitlements like political rights, health care, education or other social services.

Cities in the New York metropolitan area, though covering three states, have similar institutions

The discrepancies in institutions between Hong Kong and mainland cities, or even between mainland cities themselves, could be an obstacle to overcome if no authority has the power to coordinate services. People who relocate would not only have to give up their familiar social circles but also deal with impenetrable institutional borders.

Regardless of the validity of people’s image of Macau, the results indicate Hongkongers feel more confident about moving when the destination is socially or institutionally closer to their existing life in Hong Kong.

Transport links may facilitate population movement in the Greater Bay Area but can never be a solution to Hong Kong’s housing crisis if the disparity of institutions among cities in the bay area remains. The leadership must develop the bay area as a safe and amicable environment that has high-quality medical, educational services and a free flow of information, in addition to larger living space.

Policymakers have to plan and create a bay area that offers all-round quality of life before requesting people to move. The suggestion from the elite that people, especially the youth, stomach the high cost of commuting and digest inconveniences of institutional disparity, is closer to exile than to exodus.

Dr Hua Guo is a research associate at the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, where Dr Victor Zheng is assistant director